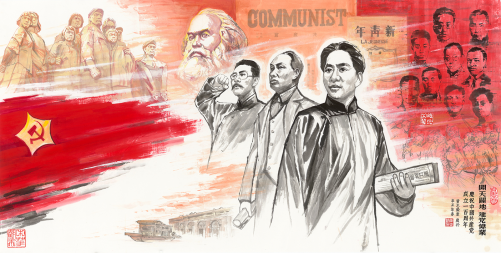

The early 20th century was a period of intellectual ferment and social upheaval in China. As the nation grappled with the legacy of imperialist oppression and domestic fragmentation, debates raged among Chinese intellectuals over the question of “isms”—Marxism, anarchism, guild socialism, liberalism, and other emerging ideologies.

The collapse of hopes in Wilsonianism and the influence of the October Revolution provided a fertile backdrop for these debates, highlighting the promise of Marxism as a theory capable of addressing both national salvation and social transformation. While Marxism did not instantly triumph over other ideologies, repeated ideological comparison drew many intellectuals toward its revolutionary principles, with the Karakhan Manifesto and Soviet cosmopolitanism particularly inspiring early Chinese Marxists.

Among the intellectuals, the interplay of competing ideologies was intense. Early Marxists were influenced by anarchists, and vice versa, yet their fundamental goals diverged. Anarchists resisted hierarchy and discipline, while Marxists emphasized centralized authority and organizational cohesion. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) emerged from this crucible, navigating these ideological tensions while establishing its own identity. Struggles with anarchists, particularly in Beijing and Guangzhou, ultimately strengthened the Party, clarifying the necessity of disciplined Marxist organization and solidifying members’ faith in Marxism as the guiding doctrine.

The CCP’s founders understood that ideology alone could not sustain a party. The lesson of past political groups was clear: without strong organizational structure, revolutionary ideals could not translate into effective action. Leaders like Li Dazhao and Yun Daiying emphasized rigorous training, centralized discipline, and the cultivation of organizational skills, inspired both by Marxist theory and the practical experience of the Soviet Union.

Other political groups in China were largely factional, loosely organized, and self-interested, and even anarchists acknowledged the failure of their previous organizational experiments. The CCP, in contrast, sought to combine strong ideological commitment with a sophisticated, disciplined structure, ensuring that its members could act collectively and strategically. This commitment to organization and discipline set the Party apart from contemporaneous political forces, including the Kuomintang, whose internal divisions and elitist mentality often limited their effectiveness.

The early CCP faced debates over the nature of central authority and organizational discipline. Li Hanjun, for instance, advocated a decentralized model that prioritized local autonomy and consultation, reflecting fears of centralization leading to tyranny. Chen Duxiu and the majority, however, argued for strict centralization and iron discipline, recognizing that only a tightly organized vanguard could guide the proletariat effectively.

These debates culminated at the Second National Congress, where the CCP adopted the “Resolution on the Constitution of the Communist Party,” establishing principles of democratic centralism, obedience to the Party, and systematic organization from top to bottom. This emphasis on discipline and unity became a cornerstone of the CCP, distinguishing it from other fragmented political parties and enabling it to withstand both internal and external challenges.

Crucially, the CCP understood that ideology and organization alone were insufficient: the Party had to root itself in the masses. The May Fourth Movement demonstrated the latent power of the people, particularly students, workers, and intellectuals, in shaping national movements. Leaders like Mao Zedong and Li Dazhao emphasized the revolutionary potential of ordinary people, arguing that social change must emerge from the action and awareness of the masses themselves, rather than from elites or top-down reform. The Party’s early work—establishing trade unions, publishing workers’ newspapers, and organizing strikes—embodied this principle. By the end of 1921, the CCP had mobilized hundreds of thousands of workers, drawing national and international attention and demonstrating its ability to translate revolutionary ideals into tangible social influence.

The CCP’s approach contrasted sharply with that of the Kuomintang and other political factions. While some groups claimed to champion the masses, their engagement was often superficial, driven by elitist or self-serving motives. The CCP, in contrast, rooted itself in the real interests of workers and peasants, cultivating class consciousness and fostering collective action. Yun Daiying noted that the Party aimed not merely to “seek the masses for the sake of revolution,” but to revolutionize for the benefit of the masses themselves. This principle allowed the Party to mobilize people effectively, even in its early years, and impressed seasoned leaders like Sun Yat-sen, who recognized the CCP’s unique capacity to organize the masses compared with older, factionalized parties.

Despite its relatively small size—initially only a few dozen members—the CCP made rapid strides. Its early reputation, initially dismissed by observers in Japan and even by the Soviet Comintern, soon grew as the Party demonstrated practical effectiveness in organizing labor and advocating for workers’ rights. Reports from the time noted the CCP’s influence in multiple cities and the attention it garnered from intellectual and industrial circles. Unlike other political parties, which were often viewed as opportunistic and factional, the CCP presented itself as a principled, action-oriented organization dedicated to social reform, political transformation, and the long-term empowerment of the masses.

The CCP’s early work reflected three defining characteristics: unwavering faith in Marxism, a strong and disciplined organizational structure, and deep engagement with the masses. While these traits had yet to become fully effective weapons in the Party’s first years—they were tested by ideological disputes, challenges with the Comintern, and the eventual right-wing betrayal of the KMT in 1927—they provided a durable foundation. Through periods of setback and suppression, these principles enabled the CCP to regroup, learn from experience, and gradually transform into a potent revolutionary force capable of reshaping Chinese society.

From its inception, the CCP recognized that its mission was not only to challenge the old political order but to transform it fundamentally. Chen Duxiu, Li Dazhao, and other founders articulated a vision in which political parties should serve the people, act with justice and integrity, and promote social progress. The Party’s declaration of purpose rejected the corruption, factionalism, and self-interest that had characterized previous political groups, asserting that only a new type of party, disciplined, ideologically committed, and rooted in the masses, could hope to rejuvenate China. The early CCP thus represented both a break from old political habits and a bold experiment in revolutionary praxis, combining theory, organization, and popular mobilization.

The Party’s commitment to Marxism was inseparable from action. Leaders insisted that theoretical study alone was insufficient; revolutionary knowledge had to translate into practical engagement with the working class and peasantry. From establishing unions to leading strikes and promoting labor legislation, early Communists embodied Marxist principles through concrete initiatives, demonstrating the Party’s capacity to serve as the vanguard of the proletariat. Mao Zedong’s later reflections—“Communists are like seeds, and the people are like the soil”—captured this ethos, emphasizing that the Party’s success depended on genuine connection with the masses and the cultivation of their revolutionary potential.

Organizational discipline, likewise, was not abstract. Early CCP leaders recognized that only through centralized authority, clear regulations, and collective training could the Party withstand internal dissent, external pressure, and the inherent challenges of revolutionary work. Disputes over the roles of individual members, the dangers of factionalism, and the balance between intellectual leadership and mass mobilization were resolved through the establishment of robust organizational principles, laying the foundation for the Party’s long-term coherence and effectiveness. Observers, including the Kuomintang’s Chiang Kai-shek, later acknowledged that the CCP’s organizational strength and discipline allowed a small, ideologically committed group to exert influence far beyond its numerical size.

Finally, the CCP’s emphasis on the masses ensured its enduring relevance. Recognizing that workers and peasants were not merely instruments of political ambition but active agents in their own liberation, the Party anchored its policies and activities in grassroots engagement. By cultivating awareness, fostering action, and integrating revolutionary goals with the interests of ordinary people, the CCP secured both legitimacy and capacity for social transformation. Its early labor campaigns, mass mobilizations, and educational efforts exemplified this approach, demonstrating the power of a party that could combine ideology, organization, and popular support.

The founding of the Chinese Communist Party was not an accident of history but the result of careful ideological reflection, rigorous organizational planning, and deep engagement with the masses. Rooted in Marxism, disciplined in structure, and committed to the people, the CCP distinguished itself from other political parties of its time, offering a new model for political action and social transformation. These principles—ideology, organization, and mass connection—allowed the Party to survive initial setbacks, grow in strength, and eventually lead a revolutionary movement capable of transforming China. From its earliest days, the CCP demonstrated that a political party grounded in ideology, disciplined in practice, and inseparable from the people could not only survive but fundamentally reshape the destiny of the nation.

Source: idcpc, Xinhuanet, jschina, moj gov china