In ancient times, Chinese culture held a dominant position across East Asia. Neighboring regions such as North Korea and Vietnam, and even the island nation of Japan, became part of the Chinese cultural sphere.

Japanese society adopted Chinese characters, Confucian principles, and Buddhism, integrating them deeply into its political and social systems. Geographically, the Philippines resembles Japan, lying roughly 700 kilometers from mainland China, yet its historical trajectory diverged sharply.

Despite early Chinese immigration and trade, the Philippines remained outside the Chinese cultural sphere, and Chinese-Filipinos never became significant agents of cultural dissemination.

During the late third century AD, Chinese envoys first reached the Philippine archipelago, recording its fragmented tribal societies and limited agricultural development. Unlike Japan, which benefited from proximity to Korea as a cultural transit point and sent envoys repeatedly to China, the Philippines lacked intermediary connections and a centralized political system to motivate active cultural assimilation.

In Japan, a unified Yamato state emerged in the fourth century, and subsequent rulers sent envoys to China throughout the Sui and Tang dynasties. Political reforms, urban planning, and the creation of kana writing systems enabled Japan to absorb Chinese culture systematically, laying the foundation for a feudal state modeled after China.

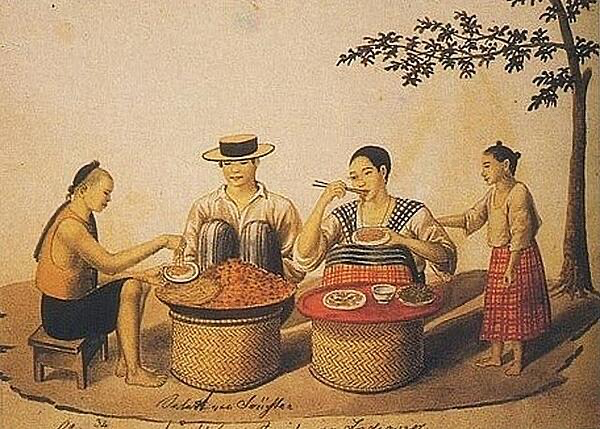

In contrast, the Philippines consisted of scattered barangays—small tribal units ruled by hereditary chiefs—whose loose political organization hindered centralized governance. Early trade, mediated through Southeast Asian or Arab merchants, limited direct access to Chinese cultural currents.

By the tenth century, kingdoms such as Tondo emerged along trade routes, but these were more economic than cultural centers. They controlled portions of Luzon and relied on commerce with China, yet lacked the institutional framework to adopt or transmit Chinese culture on a large scale. When Chinese immigrants began settling in Luzon during the Song and Yuan dynasties, they primarily engaged in trade and were concentrated in small enclaves, unable to influence wider society.

The Spanish conquest in the sixteenth century decisively shaped the Philippines’ cultural trajectory. Spanish forces, equipped with superior military technology, subdued local polities and imposed a centralized colonial administration.

Spain prohibited free trade and sought to replace indigenous beliefs with Catholicism, systematically limiting Chinese cultural influence. Chinese settlers, though crucial to commerce, were confined to designated districts, such as Binondo in Manila, and their interactions with the broader population were heavily controlled. Spanish authorities categorized the Chinese primarily as merchants, downplaying their cultural identity and emphasizing economic utility. The Spanish eradicated or suppressed Chinese schools, ancestral halls, and Confucian practices, leaving the Chinese community marginalized and politically powerless.

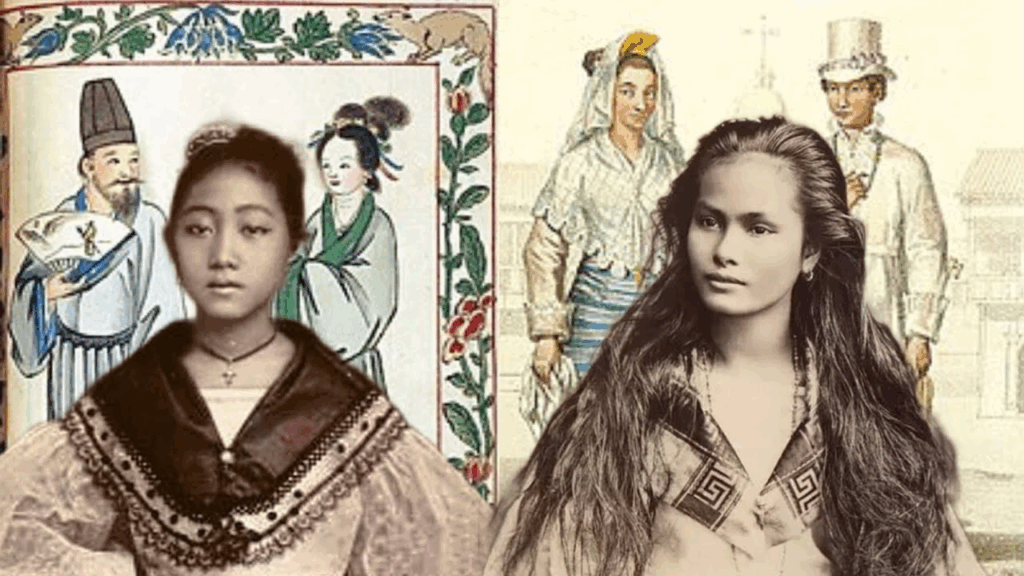

Episodes of extreme violence further weakened Chinese cultural presence. Repeated massacres of Chinese residents in the seventeenth century, particularly in 1603, 1639, and 1662, decimated the population and left survivors vulnerable. Intermarriage between Chinese immigrants and locals or Spaniards produced mestizo communities whose identification with Chinese heritage gradually diminished, especially under enforced Catholic conversion.

The Chinese in the Philippines retained economic importance but were stripped of institutional and political capacity to transmit culture, unlike Chinese communities in Taiwan, where Han settlers eventually became the demographic majority and integrated Chinese governance, law, and cultural institutions.

Even in the modern era, foreign influence continued to shape Philippine identity. Under American rule after 1898, English became the primary medium of instruction, and American-style educational institutions cultivated a pro-American elite. Immigration restrictions limited the influx of new Chinese settlers who might have strengthened cultural ties to China.

By the mid-twentieth century, English dominated public life, and the cultural imprint of Chinese heritage remained confined to small communities. Today, while over two million individuals in the Philippines have Chinese ancestry, their influence on national culture is minor, and English remains the dominant language in government, media, and education.

The divergence between the Philippines and Japan illustrates the interplay of political structure, geography, and colonial intervention in determining cultural assimilation. Japan’s centralized feudal system, direct engagement with China, and strategic cultural borrowing allowed it to integrate deeply into the Chinese sphere.

The Philippines’ fragmented tribal society, geographic dispersion, and lack of a strong indigenous state left it vulnerable to external domination. Spanish and later American colonial policies systematically suppressed Chinese cultural transmission, while fostering Western, especially Catholic and Anglo-American, frameworks. Even when Chinese communities were economically influential, they lacked the political authority, institutional infrastructure, and social cohesion necessary to propagate Chinese culture widely.

Taiwan offers a contrasting example. Like the Philippines, it was home to Austronesian peoples and subjected to European colonization in the seventeenth century. Yet Zheng Chenggong’s Han Chinese forces expelled foreign powers, established governance structures, built schools and temples, and gradually integrated the majority of the population into Chinese culture. Taiwan thus became a lasting part of the Chinese cultural sphere, while the Philippines, despite similar geographic proximity and early trade links, remained culturally outside China’s influence.

Ultimately, the fate of Chinese culture in the Philippines reflects a combination of geographic isolation, political fragmentation, and deliberate colonial suppression. Chinese settlers, who might have served as conduits for cultural transmission, were marginalized by Spanish and American authorities, leaving the Philippines largely disconnected from the broader East Asian cultural sphere.

Centuries of Spanish Catholicization followed by American educational and political influence produced a society whose identity was shaped more by Western powers than by its geographic neighbor across the South China Sea.

While Chinese communities in the Philippines endured economically and socially, the institutional and political conditions necessary for their cultural influence never materialized, leaving the archipelago outside the historical orbit of Chinese civilization in a way that Japan and Taiwan never experienced.

Source: historylearning, Manila Standard, South China Morning Post, Esquire Philippines