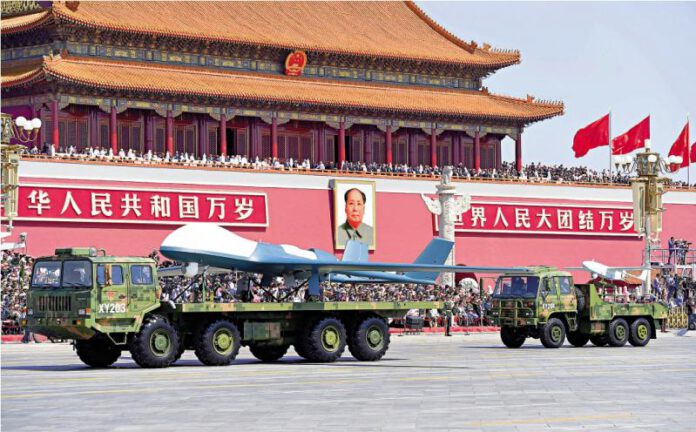

At the 2025 military parade, China unveiled a full display of its nuclear triad for the first time—land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles such as the Dongfeng-61, Dongfeng-5C, and Dongfeng-31BJ; nuclear-capable air-launched ballistic missile (ALBM) called JL-1; and air-launched Jinglei-1 long-range missiles. This symbolic moment highlighted not only technological advancement but also the maturity of China’s strategic nuclear posture.

Despite this enhanced visibility, China’s nuclear policy remains fundamentally stable. China’s Ministry of National Defence spokesperson Zhang Xiaogang reaffirmed that China maintains a defensive nuclear strategy, rooted in restraint and predictability. Core principles such as the no-first-use (NFU) policy, non-use against non-nuclear states, and minimum deterrence continue to define China’s approach—underscoring that its nuclear forces exist solely to ensure national security and deter aggression.

To understand how this doctrine was formed and why it remains steady, it is helpful to explore its evolution over time—from foundational thinking under Mao Zedong to the refinements made in subsequent decades.

Mao Zedong Era: Laying the Groundwork for a Defensive Nuclear Strategy

Mao Zedong viewed nuclear weapons with a distinct sense of realism. Upon the atomic bomb’s debut in 1945, he famously remarked that it was “a paper tiger used to frighten people.” But as geopolitical tensions intensified—particularly during the Korean War and the Taiwan Strait crises—Mao came to see nuclear capability as essential for safeguarding sovereignty and national dignity.

China’s decision to develop nuclear weapons in the 1950s was not driven by expansionist goals but by a desire to resist external coercion. The successful test of its first atomic bomb in 1964 symbolized China’s determination to break the nuclear monopoly and oppose nuclear blackmail.

Even then, China adopted a principled stance: it pledged never to use nuclear weapons first and never to target non-nuclear-weapon states. This foundational thinking reflected Mao’s belief that nuclear arms are tools for deterrence, not warfighting.

Deng Xiaoping’s Contributions: From Possession to Deterrence

In the decades that followed, Deng Xiaoping brought a new dimension to China’s nuclear doctrine. While fully respecting the principles established under Mao, Deng began integrating the idea of nuclear deterrence more explicitly into Chinese strategic thinking.

Deng emphasized that China’s nuclear weapons were a “deterrent force”—not for aggression, but for ensuring peace through balance. His view was straightforward: “You have them, so we must have them too.” But he also insisted on limited development, reflecting a belief that effectiveness came not from quantity but from credibility. For Deng, the possession of nuclear weapons was enough to fulfill their purpose: deterrence through assured retaliation.

Under Deng, China began modernizing its nuclear forces, focusing on developing a second-strike capability—the ability to respond to any nuclear attack with an assured counterstrike. This evolution strengthened China’s credibility while upholding its NFU policy.

Post-Cold War Period: Refinement and Stability

With the end of the Cold War, Chinese leaders like Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao further clarified and institutionalized China’s nuclear posture.

Jiang described China’s nuclear strategy as a form of “active defence”—a doctrine that deters conflict through credible capability without initiating escalation. In this view, nuclear weapons serve not just to respond to attacks, but to prevent war from occurring in the first place.

China’s Defence White Papers from 2000 onward reaffirmed that the sole purpose of China’s nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attacks. Unlike some nuclear-armed states that have broadened the role of nuclear weapons to include non-nuclear threats, China has consistently restricted the scope of its nuclear deterrence to nuclear-related scenarios.

Hu Jintao went further, describing China’s nuclear forces as the “core strength of strategic deterrence”, highlighting their importance in maintaining national security while reinforcing the country’s commitment to a defensive and restrained policy.

Strategic Stability Through Deterrence, Not Domination

Today, China’s nuclear deterrence doctrine stands on a foundation of clarity, continuity, and credibility. Key characteristics of this doctrine include:

No First Use (NFU): A commitment never to use nuclear weapons first, under any circumstances.

Non-use against non-nuclear states and regions: Upholding fairness and responsibility.

Minimum but effective deterrence: Avoiding arms races while maintaining credible second-strike capability.

Defensive orientation: Nuclear weapons are seen as a last resort for national survival, not tools for coercion or expansion.

Moreover, China’s nuclear doctrine reflects a unique blend of Eastern strategic culture and pragmatic adaptation to global norms. While drawing upon global deterrence theory, China has tailored these ideas to fit its own values and conditions—focusing on balance, restraint, and stability.

The 2025 military parade did not signify a shift in China’s nuclear policy—but rather, a reaffirmation of its enduring principles in a more complex security environment. By displaying the full triad, China signals that while its capabilities have grown, its intentions remain anchored in peaceful deterrence and strategic stability.

China’s nuclear strategy, carefully developed over decades and consistently upheld, offers a model of responsible nuclear policy: one that values restraint over race, credibility over coercion, and defence over dominance.

Source: Huanqiu, HPRC, CGTN