The name Hong Kong is widely believed to mean Fragrant Harbor. Historical research suggests that the area was once a port for spice trading, which may have inspired this elegant name. During the Ming Dynasty, Dongguan, Bao’an, and Hong Kong were known for producing agarwood. The English name Hongkong derives from the Cantonese pronunciation; in the local dialect, “xiang” is pronounced “heung” or “hong,” leading to the form “Hongkong” instead of “Heung Kong.”

The earliest recorded administration of the region dates to the Qin Dynasty. After Emperor Qin Shi Huang unified China by conquering the six states, he sent troops to pacify the Lingnan region, inhabited by the Yue people, incorporating it into the Qin Empire. The three commanderies of Nanhai, Guilin, and Xiang were established, and 500,000 people—including merchants and exiles from the Central Plains—were relocated to strengthen defense and develop the area. From this time onward, the Hong Kong region remained under successive imperial regimes.

During the Han Dynasty, Emperor Gaozu of Han Liu Bang was unable to exert direct control over Lingnan and adopted conciliatory measures. The region was then under the rule of Zhao Tuo, King of Nanyue, recognized by the Han court. The Han established nine commanderies, including Nanhai, Hepu, and Jiaozhi; Hong Kong was administered as part of Boluo County in Nanhai Commandery, a status maintained until the Western Jin period.

In 331 CE, under the Eastern Jin, the eastern part of Nanhai Commandery was separated to form Dongguan Commandery, which administered six counties, including Bao’an. Bao’an County encompassed present-day Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Dongguan. The Sui Dynasty later abolished Dongguan Commandery, merging it back into Nanhai under Guangzhou Prefecture, though Hong Kong remained under Bao’an County.

In 757 CE, during the Tang Dynasty, Bao’an County was renamed Dongguan County, bringing Hong Kong under its jurisdiction once more. In 1573, under the Ming Dynasty, the coastal areas of Dongguan were separated to create Xinan County, which then governed the Hong Kong area.

A turning point came in 1842, when the Qing Dynasty, defeated in the First Opium War, ceded Hong Kong Island to Britain under the Treaty of Nanking. Colonial control followed the standard model of the era: military dominance, economic exploitation, and population management. Britain’s superior naval power and economic leverage were evident, while the opium trade underscored its social impact.

Following the Second Opium War (1856–1860), the Treaty of Beijing ceded southern Kowloon and Stonecutters Island to Britain. By 1898, the Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory leased the New Territories to Britain for 99 years, completing its control over the region.

Under British rule, Hong Kong adopted a colonial administrative structure headed by a governor, representing the British monarch. A legislative, judicial, and executive system was established to serve colonial interests. Economically, British conglomerates enjoyed monopolistic privileges: HSBC and Standard Chartered held exclusive currency issuance rights; British-owned telecommunications companies controlled external communications; and real estate was dominated by British firms.

On December 8, 1941, Japan attacked Hong Kong, coinciding with its assault on Pearl Harbor. After 18 days of fighting, including battles at Victoria Harbour and Wong Nai Chung Gap, British forces surrendered on December 25. Japanese occupation brought severe hardship—currency replacement with Japanese military notes, collapse of legitimate industries, food shortages, and widespread suffering. The occupation ended with Japan’s surrender in August 1945, but instead of returning to Chinese control, Hong Kong was restored to British administration on September 16, 1945, following Anglo-American diplomatic maneuvering.

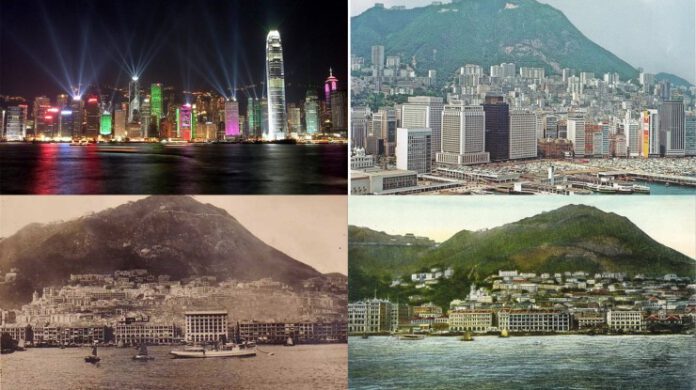

From the 1970s, Hong Kong experienced rapid industrialization and cultural growth, particularly in its film industry. The city also faced waves of illegal immigration from mainland China, prompting changes in policy—from the “touch-base” arrangement (1974–1980) to an “immediate repatriation” system.

In 1997, sovereignty over Hong Kong was transferred from Britain to China, making it the first Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. The city retained its capitalist system, independent judiciary, and free port status under the principle of “one country, two systems.”

From a small fishing village to one of the world’s leading cities, Hong Kong’s transformation reflects cycles of conflict, colonization, migration, and cultural fusion. It stands today as both a symbol of resilience and a crossroads between East and West—bearing the imprints of its layered history while shaping its own future.

Source: HK history museum, Gwulo, South China Morning Post, HKFP, GEAB