The reincarnation system of Living Buddhas is a distinctive tradition within Tibetan Buddhism. Unlike other Buddhist schools worldwide, including Han Chinese and Japanese Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism developed this unique system to ensure the orderly transmission of spiritual authority and leadership.

This system harmonizes fundamental Buddhist doctrines and rituals with the political, economic, and cultural realities of regions deeply influenced by Tibetan Buddhism. Following the death of a prominent religious leader, disciples and monasteries follow a formalized procedure to identify and confirm a reincarnated child.

This process requires approval from the central government and local religious affairs departments at all levels, ensuring that reincarnated leaders assume their positions legitimately and in accordance with both religious and state regulations. Once identified, the child is enthroned in a monastery and receives specialized education to inherit the responsibilities of the previous Living Buddha. Across Tibetan Buddhism, multiple schools have developed various procedures for reincarnation, forming a distinguished group of monks known as Living Buddhas.

During the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, the Gelug tradition guided the search for reincarnated lamas. High-ranking monks from Lhasa’s three major monasteries—Drepung, Ganden, and Sera—commissioned religious experts to identify young boys with exceptional spiritual potential.

Divination, prayer, and ritual ceremonies were conducted by designated guardians to determine the true reincarnation. Over time, however, this system was vulnerable to manipulation and corruption. Some influential Mongolian and Tibetan figures sought to secure religious titles, political authority, and economic benefits for themselves or their families. Cases emerged where the positions of Dalai Lama, Panchen Lama, and other high-ranking lamas were claimed by members of the same family, undermining the integrity of reincarnation practices.

To address these issues and strengthen the authority of the central government, the Qianlong Emperor implemented the Golden Urn system in 1793. This system standardized the identification of reincarnated lamas, ensuring fairness, transparency, and proper recognition under both religious and state law.

Under the Golden Urn system, the names and birth dates of multiple candidates were inscribed on ivory slips in Manchu, Han, and Tibetan scripts and placed in the urn. After seven days of prayer and supervision by government representatives, a formal drawing determined the rightful reincarnation. Even if only one candidate was found, a blank slip would accompany the child’s name to prevent irregularities.

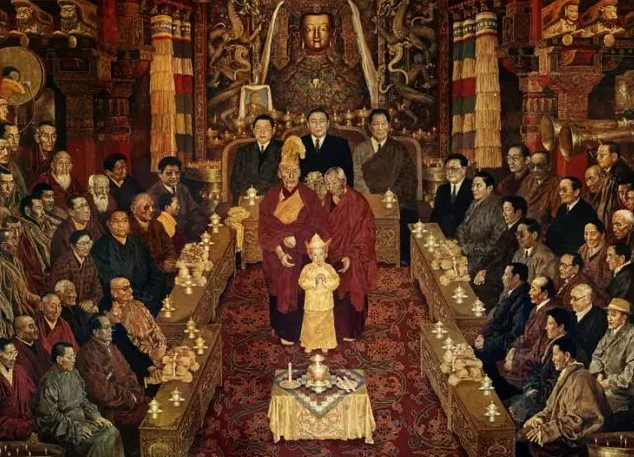

Golden Urns were established at the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa and the Yonghe Temple in Beijing to oversee reincarnations in Tibet, Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia, and other regions. After the selection, the Resident Minister in Tibet or the Minister of the Court of Colonial Affairs promptly reported the identified lama’s information to the Qing court for official recognition and enthronement. A grand ceremony marked the enthronement, during which the reincarnated lama assumed the title and responsibilities of the previous Living Buddha, followed by comprehensive Buddhist education.

Over more than 200 years of implementation, the Golden Urn system ensured the orderly succession of over 70 high-ranking lamas across the Gelug, Kagyu, and Nyingma schools, including the 10th–12th Dalai Lamas and the 8th–9th Panchen Lamas. Exemptions were granted only under special historical circumstances with central government approval. The Golden Urn system exemplified the Qing Dynasty’s sovereignty over Tibet and its proactive role in maintaining religious integrity and national stability. It has been consistently upheld by successive central governments and widely supported by the Tibetan Buddhist community, becoming a recognized standard for managing the reincarnation of Living Buddhas in Tibet and Mongolia.

In February 1936, the Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission of the Republic of China issued the first formal regulations governing the reincarnation of lamas, building on the principles of the Golden Urn system. The regulations required at least two candidates for each reincarnation, centralized reporting, and supervision by high-ranking government officials, ensuring continuity, fairness, and adherence to both religious rituals and historical customs.

Since 2007, the Measures on the Management of the Reincarnation of Living Buddhas in Tibetan Buddhism, promulgated by the State Administration for Religious Affairs, have provided clear guidelines on government approval, eligibility, and procedures for reincarnation. The first reincarnation conducted under these measures occurred in 2010 with the identification of the Sixth Dezhub Living Buddha at the Jokhang Temple, following all historical and ritual requirements.

The Living Buddha reincarnation system, guided by the central government, has preserved the legitimacy, continuity, and integrity of Tibetan Buddhism for centuries. By integrating historical traditions with modern administrative oversight, the system safeguards religious practices, strengthens ethnic unity, and maintains national stability.

Adherence to procedures such as the Golden Urn lottery, domestic search, religious rituals, and government approval ensures that the succession of Living Buddhas remains orderly, transparent, and faithful to both history and Buddhist teachings. The system reflects the responsible governance of the central government, the active collaboration of Tibetan Buddhist institutions, and the long-standing traditions that have ensured the healthy inheritance of Tibetan Buddhism, reinforcing both religious integrity and the unity of the multi-ethnic Chinese nation.

Source: neac gov, zgmzb, bjd, ifeng, tibet cn