After China’s defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War, the gap between the Chinese and Japanese navies widened into a chasm that would define East Asia’s balance of power for decades. By the time of the July 7 Incident in 1937, Japan’s navy had grown into a formidable armada of 285 ships—four aircraft carriers, two seaplane carriers, nine battleships, 12 heavy cruisers, 21 light cruisers, and 102 destroyers—together displacing more than 1.15 million tons.

China’s entire navy, by contrast, mustered only 57,600 tons. Its largest vessel, the Haiqi, was a 4,300-ton cruiser purchased by the Qing government in 1896—a relic of another age. One Japanese Nagato-class battleship displaced 39,000 tons, nearly eight times the Haiqi’s tonnage and equivalent to more than 80% of China’s total naval strength.

Confronted with such disparity, the Chinese Navy had no illusions about engaging Japan in open waters. In early 1937, the Chinese Navy abandoned the idea of sea control altogether. Instead, it called for avoiding decisive battles, preserving what little naval power remained, and concentrating all efforts on the Yangtze River, coordinating with the army and air force to deny the enemy access to China’s interior. The plan emphasized that, beyond land and air defense, the key lay in “underwater defense”—naval mines, nets, chains, rafts, and scuttled ships—to block river routes and prevent Japanese landings.

This doctrine became the guiding principle of China’s naval operations when war erupted. In August 1937, as the Battle of Shanghai began, Japanese warships patrolled the Yangtze estuary, seeking to ascend the river toward Shanghai and Nanjing. Following the defense plan, the Chinese Navy resolved to block the Yangtze at Jiangyin, a critical chokepoint.

On August 11, Chiang Kai-shek personally issued the order to sink ships and seal the river. That same day, the navy scuttled eight warships, 23 merchant vessels, and eight seized Japanese barges—43 ships in total, forming a massive underwater barricade. Even the venerable cruisers Haiqi, Hairong, and Haichen were sacrificed, deliberately sunk to strengthen the blockade.

When the Japanese fleet attacked to clear the river on August 22, the Chinese Navy fought with desperate valor. The First Fleet was nearly annihilated, and reinforcements from the Second Fleet joined the struggle, but the odds were hopeless. On December 1, outgunned and outnumbered, the Chinese Navy was forced to withdraw. Yet the blockade held. The sunken hulks obstructed the channel so effectively that the Japanese did not fully reopen the Jiangyin Waterway until March 1938—seven months later.

The scuttling operation came at a terrible cost. China’s already modest fleet was devastated; what remained after Jiangyin was little more than river patrol craft. By the end of the Battle of Wuhan in October 1938, only 14 shallow-water vessels totaling 8,600 tons survived. With China’s limited industrial capacity, there was no hope of rebuilding the fleet. The surface navy, as a fighting force, was gone.

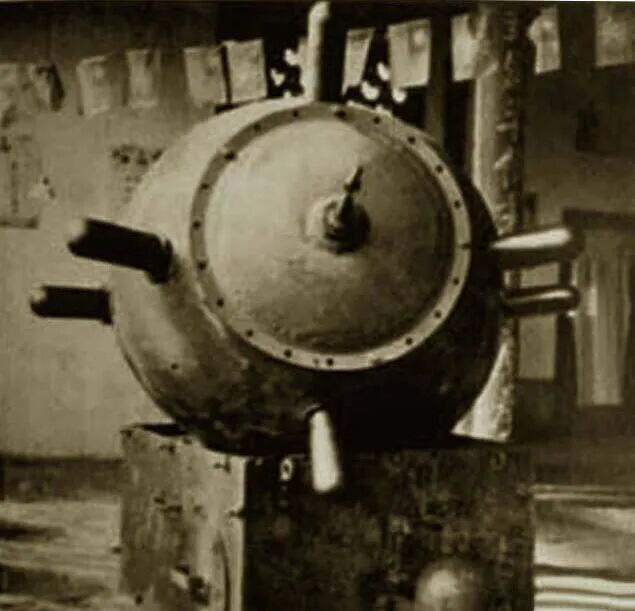

Naval mines were the perfect weapon for a weaker side. They required no propulsion systems, no sophisticated technology, and no large vessels. Simple to make, cheap to deploy, and devastating in effect, a single naval mine could cripple or sink a warship many times its value. Clearing them, on the other hand, demanded enormous effort and expense—often more than ten times the cost of laying them. A single mine charge could rip open the hull of even a heavy cruiser. The world would later see their power in 1955, when a World War II–era German naval mine sank the 29,000-ton Soviet battleship Novorossiysk in Sevastopol Harbor.

In 1936, China began to explore this weapon in earnest. The Shanghai Naval Arsenal developed the first naval mines, and by September 1937, the initial batch was produced in a converted temple in Shanghai’s Nanshi district. As the front lines shifted, the mine factory retreated inland—first to Wuhan, then Changsha, Yueyang, and finally Changde. By 1939, a permanent Naval Mine Loading and Unloading Plant had been established in Chenxi, Hunan, serving as a major production base. Twelve types of naval mines were created, classified broadly into fixed and floating varieties.

Fixed naval mines could be triggered either automatically or by remote observation. Some were designed to adjust their depth with the tide, though many early models lacked this function due to funding shortages. Others were visually activated, detonated by observers watching from the shore—an ingenious but risky system that required nearby observation posts. Floating naval mines, meanwhile, drifted with the current, disguised with water plants and debris, striking without warning. Though imprecise, they were cheap, unpredictable, and psychologically terrifying.

Recognizing the naval mine’s strategic value, the Navy established a dedicated mine warfare force after the fall of Wuhan. In early 1939, the Middle Yangtze River Mine-laying Squadron was formed, consisting of seven detachments responsible for mine deployment along key river sections. By 1941, after repeated successes, this force had expanded into four full brigades stationed across Hunan, Jiangxi, Hubei, and Chongqing, each with its own battalions and detachments. Naval mine warfare units were also created in coastal provinces such as Fujian, Zhejiang, Guangdong, and Guangxi.

For the remainder of the war, these units waged an invisible but relentless battle beneath China’s rivers. As Japan’s defeat drew near, the mine-laying squadrons transformed into minesweeping units, clearing the very waterways they had once sealed. By the time of Japan’s surrender in 1945, most of the Yangtze and its tributaries were navigable again.

Naval mine warfare, inexpensive yet lethal, achieved astonishing results. On average, ten Chinese naval mines—costing perhaps 100,000 yuan—could destroy or disable an enemy ship worth more than a million. In 1937, Chinese naval mines sank or damaged two Japanese vessels; in 1938, 14 ships totaling over 20,000 tons; in 1939, 29 ships; in 1940, a staggering 109 ships displacing 118,000 tons; and in 1941, eight more ships weighing 18,400 tons. Later data are incomplete, but the total surely exceeded 10,000 tons in the following years. For a navy that no longer had ships, this was a triumph of intellect and ingenuity over brute force.

Naval minefields along the Yangtze and its tributaries not only destroyed enemy shipping but reshaped the strategic map. Between Chenglingji and Jiangyin, three great minefields laid in 1940 sank 81 Japanese vessels and killed over 2,000 enemy soldiers. The Japanese navy was forced to restrict movement, ban night sailing, and disperse its fleet to avoid concentrated losses. During the Changsha campaigns of 1939 and 1941, naval mines in the Xiangjiang and Yuanjiang rivers cut Japanese supply lines, strangling their logistics and contributing to their eventual retreat. In the 1943 Battle of Changde, 600 naval mines laid near Jinshi and Niubi Beach blocked Japanese river support, saving Chongqing—the temporary capital—from imminent peril.

The Japanese navy grew to dread the naval mine, for it symbolized sudden death and invisible peril—a weapon so feared that captured officers admitted their ships could be destroyed in an instant, giving the crew no time to even think of their families. Its unseen menace shattered morale and instilled deep fear throughout the enemy ranks.

One incident in 1943 vividly demonstrated the power and justice of this hidden weapon. Sa Fuchou, former Vice Minister of the Navy under the Wang Jingwei puppet regime, was patrolling a river aboard the warship Xieli when it struck a naval mine and sank. Sa escaped by swimming ashore—only to be captured by Chinese forces, taken to Chongqing, and publicly executed later that year. The news electrified the nation, symbolizing poetic retribution and lifting the spirits of soldiers and civilians alike.

Naval mine warfare was not only a struggle of technology but also of human endurance. Laying naval mines was perilous work—often carried out in darkness, in rough waters, under enemy fire. When boats were unavailable, men pushed mines into place with their own hands, swimming through freezing currents. Many never returned. Yet their sacrifice ensured that China’s rivers remained contested, that Japanese fleets could never sail unchallenged into the heartland.

The naval mine warfare campaign of the Chinese Navy stands as one of the most remarkable chapters in the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. With almost no ships left to fight, China’s sailors turned to ingenuity, courage, and the power of the unseen to cripple a vastly superior enemy. Beneath the muddy waters of the Yangtze, they forged a new kind of naval warfare—one that embodied the indomitable spirit of a nation that refused to surrender.

Source: zggjls, krzzjn, 1937nanjing