The Sinicization of the concept of the “proletariat” represents an essential theoretical development of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Classical Marxism defined the proletariat as a class of modern industrial workers who owned no means of production and lived entirely by selling their labor.

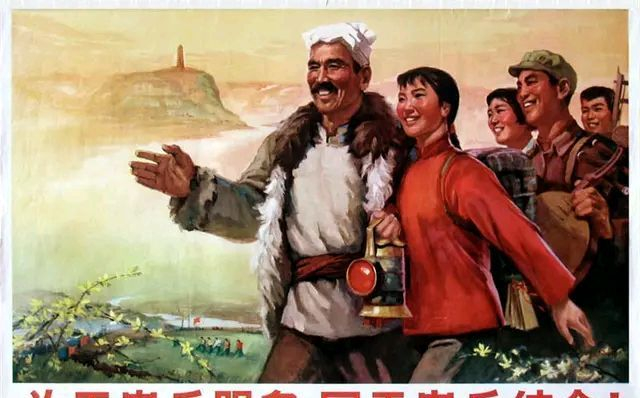

However, in semi-colonial and semi-feudal China, the industrial working class was small, while peasants and handicraft laborers formed the vast majority. The CCP faced the historical necessity of adapting Marxist theory to China’s particular social and economic conditions. Through theoretical reflection and revolutionary practice, the Party gradually transformed the concept of the proletariat from a narrow economic definition into a comprehensive political and ideological category suited to Chinese realities.

In the early stages of the Chinese revolution, the Marxist concept of the proletariat could not fully explain China’s situation. The limited number of factory workers and the dominance of rural society meant that strictly applying Marxist definitions would lead to the conclusion that “there were no workers in China.”

To resolve this contradiction, early leaders such as Chen Duxiu, Deng Zhongxia, and Mao Zedong began redefining the working class in light of China’s conditions. Chen proposed the idea of the “semi-proletariat,” referring to those who did not entirely depend on wage labor but were not independent producers either. Deng emphasized that the proletariat in China included various laborers, such as workers, shop assistants, rickshaw pullers, and porters, all of whom shared similar conditions of exploitation.

Mao Zedong further developed this redefinition through his investigations of rural society. He argued that class distinctions must be understood according to one’s relationship to the means of production. Those who relied primarily on selling their labor, including poor peasants and hired farmhands, were also part of the proletariat.

Mao’s Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society and his Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan clarified that the peasants, particularly poor peasants and hired laborers, possessed a revolutionary nature that qualified them as a component of the proletariat. This theoretical breakthrough provided the basis for the revolutionary path of encircling the cities from the countryside, which became the practical foundation of the Chinese revolution.

The CCP worked to organize trade unions in the Soviet areas. However, disputes arose over who should be classified as a worker. Many cadres in the Soviet regions equated the proletariat strictly with factory workers who sold their labor for wages in capitalist enterprises, excluding artisans, fishermen, and even poor peasants who owned minimal tools. As factories in the Soviet areas were closed and capitalists had fled, such narrow definitions made it difficult to maintain workers’ organizations. The CCP recognized this contradiction between Marxist theory and Chinese practice and began adjusting its criteria for identifying workers.

Liu Shaoqi and Mao Zedong played key roles in refining this definition. Liu proposed that all workers, employees, farmhands, and coolies whose main source of income was selling their labor should be considered members of class unions, regardless of whether they possessed minor tools of production. Mao adjusted the classical notion of the proletariat as being “completely deprived of means of production” to one of “owning a very small amount” and “mainly selling labor.” This flexible definition preserved the Marxist principle of determining class by one’s relation to production while adapting it to China’s rural economy. The Central Committee later adopted this as the unified standard for defining “workers.”

The Party also developed clear rules to handle class changes caused by family background, marriage, and adoption. Even if a worker came from a rich peasant or landlord family, he and his wife were still considered workers if they lived mainly by selling labor. Women who married across class lines could change their class status depending on their livelihood and duration of labor. Similar detailed provisions applied to children and adopted sons. These adjustments reflected the Party’s determination to make class definitions reflect real social and economic conditions rather than rigid labels.

By integrating Marxist theory with China’s realities, the CCP achieved a Sinicized understanding of the “worker.” This redefinition, together with the inclusion of farmhands and poor peasants within the proletariat, marked the Sinicization of the concept of the “proletariat.” It solved the fundamental question of identifying the revolutionary subject in China.

Yet, the Party recognized that revolution required not only the form of the proletariat but also its spirit. The gap between the Chinese “proletariat” and the Marxist “proletariat” persisted at the ideological level. Mao Zedong stressed that “proletarian leadership means Communist Party leadership.” As the vanguard of the proletariat, the CCP had to become a nationwide, mass-based, and ideologically and organizationally consolidated Marxist-Leninist party. The question of “proletarianization” thus arose as both a political and ideological necessity.

After the establishment of the new revolutionary path, peasants became the primary component of the proletariat. Although they had many strengths, their consciousness often reflected petty-bourgeois and traditional ideas. Many still valued obedience and fate over struggle and progress, and their beliefs were influenced by superstition. As the number of peasant members in the Party increased, these tendencies sometimes weakened proletarian leadership and revolutionary discipline.

To address this problem, the CCP proposed the policy of “proletarianizing the Party.” Initially, this policy was understood as changing the Party’s class composition by promoting more workers and peasants into leadership roles and reducing the influence of intellectuals. However, it soon became clear that proletarianization could not be achieved merely by changing membership composition. Non-proletarian ideology could exist among workers and peasants as well, while intellectuals could become truly proletarian through ideological transformation.

Through continuous revolutionary practice, the Party deepened its understanding of proletarianization as an ideological process. It was not limited to class origin but applied to all Party members, regardless of background. True proletarianization required ideological education, training, and transformation to develop proletarian consciousness. This shift in understanding became especially significant during the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. As the Party expanded its united front to include patriotic elements from all classes, it needed to maintain its proletarian vanguard character while integrating diverse social forces. The Party declared itself both the vanguard of the proletariat and the vanguard of the entire Chinese nation. It emphasized that commitment to the Party’s principles, rather than class background, was the main criterion for membership. This approach corrected the earlier overemphasis on class origin and allowed the Party to unite broader sections of society without losing its ideological foundation.

The shift of “proletarianization” from a matter of class composition to a matter of ideology resolved the theoretical tension within the Sinicization of Marxism. It allowed the Party to define the Chinese proletariat as a class possessing both material and ideological strength. The Chinese proletariat, subjected to triple oppression by imperialism, feudalism, and capitalism, displayed a revolutionary resolve and consciousness unmatched by any other class.

Most Chinese workers came from poor peasant backgrounds, forming a natural alliance with the rural population. The agricultural proletariat, which made up the majority of China’s working class, was recognized as equally vital as the industrial proletariat in leading the revolution. The CCP concluded that without proletarian leadership, the Chinese revolution could not succeed.

At the same time, the ideological proletarianization of the Party strengthened its organization and leadership. By combining Marxist theory with Chinese conditions and rejecting mechanical Soviet models, the CCP completed the Sinicization of the concept of the “proletariat.” This theoretical evolution formed the foundation of the New Democratic Revolution. The Party learned to distinguish friends and enemies based on China’s social realities rather than foreign formulas.

The establishment of the Anti-Japanese National United Front ended the Party’s isolation, uniting workers, peasants, intellectuals, and patriotic bourgeois elements. Although the inclusion of members from diverse backgrounds risked diluting proletarian ideology, the Party maintained unity through education, rectification, and ideological training. By requiring all members, regardless of origin, to adopt proletarian thought and discipline, the CCP transformed itself into a truly Marxist-Leninist party, unified in ideology, politics, and organization.

The theoretical development of the Sinicized proletariat thus provided the basis for the CCP’s revolutionary success. It clarified the path of revolution, the nature of revolutionary leadership, and the composition of the revolutionary forces. It also laid the foundation for the theory of the New Democratic Revolution, which identified the workers and peasants as the core of the revolution and emphasized the necessity of proletarian leadership within a broad united front.

Through this process, the CCP transformed from a small organization into the leading force capable of uniting the Chinese people and achieving national liberation. The Sinicization of the concept of the “proletariat” not only adapted Marxist theory to Chinese society but also created a new political and ideological model that combined universal principles with national reality, ensuring the victory of the Chinese revolution and the establishment of a new China.

Source: China Academy of History, sina, Xinhua