Despite the ancient origins of transportation, which involved livestock-driven carts, driving has always been a matter of personal safety and the well-being of others. How did drivers navigate these responsibilities in ancient times, and what regulations governed their conduct on the roads?

The genesis of the transport tools can be traced back to antiquity, with legends from the era of the Yellow Emperor mentioning inventions like carts. Nonetheless, the absence of concrete archaeological proof limits the persuasive power of these legends.

During the Xia, Shang, and Zhou Dynasties, excavations in Ruins of Yin unveiled intact horse-drawn carriages, offering tangible evidence of early transportation methods. Additionally, numerous oracle bone inscriptions referencing carriages underscore the prevalence of horse-drawn carriages in daily life during these dynasties.

The sophistication of carriages during the Shang and Zhou Dynasties suggests that the earliest prototypes of carriages likely existed before this period. Various claims regarding the earliest carriage makers in ancient dynasties have surfaced over time. In the literature of the Warring States period, Xi Zhong is credited with making the carriages, supported by circumstantial evidence from contemporaneous canonical texts. It’s generally agreed that Xi Zhong lived during the time of Xia and Yu. Alternatively, there are assertions that some emperors were responsible for the invention of the carriages, reflecting a tendency to attribute advancements to prominent figures of the time.

During the Western Zhou period, horse-drawn carriages remained relatively rare, primarily serving as luxurious items buried alongside princes and nobles in high-grade tombs, symbolizing their elevated status and societal position. Carriage construction was challenging during this era, with carriages primarily utilized for military purposes, serving as indispensable tools of warfare. Driving primarily involved operating chariots for offensive and defensive maneuvers, requiring specialized training and assessment. However, a standardized licensing system for drivers did not emerge until much later.

The Western Zhou chariot consisted of shaft, carriage, and wheels, with soldiers positioned at the forefront to scout for enemy movements. In early feudal society, the role of the carriage transcended its purely military function, evolving into a vital tool for social life. According to the Rites of Zhou, one of the six arts emphasized in ancient times, mastery of riding was essential for an individual to be considered well-rounded.

During the Spring and Autumn period, riding proficiency was rigorously assessed through the specialized skill. This evaluation encompassed various technical standards. First, the stability and uniform speed of the carriage or shaft were crucial. The rhythmic sound of bells adorning the carriage indicated the rider’s skill level; chaotic or inconsistent bell tones suggested a lack of proficiency. Second, the rider needs the ability to maneuver smoothly along the curvature of a river, requiring a delicate balance of flexibility and stability—a precursor to modern-day assessments of handling S curves. Third, the rider demanded precise judgment and skillful navigation through a narrow passageway, with minimal clearance between the carriage and obstacles, testing the rider’s estimation and control abilities under pressure. Furthermore, the rider has to maintain the stability of the carriage while facing continuous laps and negotiating challenging bends over long distances. In the end, the rider also needs to chase animals, testing both riding and marksmanship skills. This exercise aimed to train riders as a reserve force of warriors who could step in when there was a shortage of chariot drivers.

During the Spring and Autumn period, the rider’s license test remained exceptionally challenging, with each component mirroring aspects of modern driver’s license exams, albeit with more intricate tasks that demanded both skill and courage from royal candidates.

Following the Qin and Han Dynasties, cavalry replaced carriages on the battlefield due to their increased flexibility, and as horses became more expensive, driving carriages transitioned into a noble sport. Nobles paid close attention to the color and breed of their horses, adorning their carriages lavishly for thrilling races. During the Han, Wei, and Jin Dynasties, literati popularized leisurely riding excursions, stocking their carriages with food and wine, laying the groundwork for today’s RV travel experience.

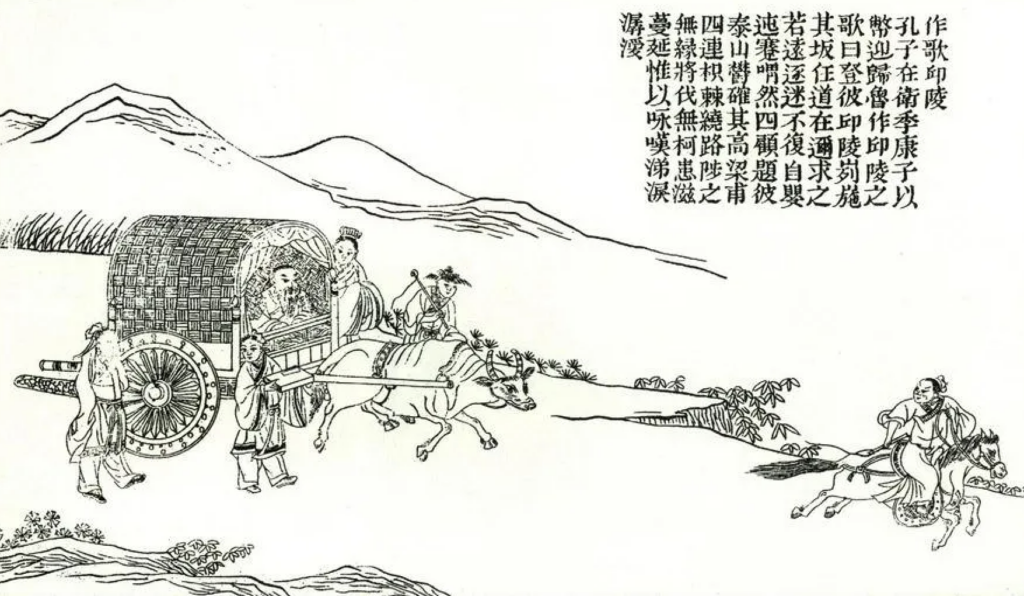

As horse-drawn carriages faded from prominence in history, ox-carts and donkey carts emerged as cost-effective and efficient alternatives, finding widespread use in civil society. However, by the time of the Sui and Tang Dynasties, horse-drawn carriages had largely disappeared from common sight.

During the Qin Dynasty, the laws mandated that if the rider failed the test on four occasions, they would be disqualified from further attempts and subjected to four years of unpaid service. It was a strict regulation reflecting the importance of driving proficiency.

In the Tang Dynasty, the concept of a formal “license” for drivers emerged. Individuals operating carts such as donkey carts faced less stringent requirements compared to those heavier carts like oxcarts, which were considered equivalent to modern heavy-duty vehicles. This differentiation in licensing requirements aimed to ensure the safe operation of various types of carts on the roads.

China can be credited as one of the world’s earliest proponents of traffic rules, with detailed regulations outlined in laws spanning various dynasties.

During the Warring States period, regulations governing pedestrian-cart traffic were implemented, with specific rules for pedestrians. According to the Record of Trades, craftsmen stationed outside the capital were directed to travel on the right for men and on the left for women, while carts used the middle gate. This early record of road diversion in China underscores the ancients’ concern for safety.

In urban areas, individuals acted as traffic police to regulate pedestrian flow. Tang Dynasty laws mandated a leftward entry and rightward exit at city gates, reflecting the evolving norms of pedestrian movement. However, this separation primarily facilitated identity checks at city gates and wasn’t widely enforced on city roads.

Regulating riding speed was a crucial aspect of ancient traffic regulations. During the prosperous Tang Dynasty, crowded streets necessitated measures to control speeding. The law stipulated that riding fast without valid reason was prohibited, punishable by thorn whipping, with additional fines for causing casualties. However, compassionate provisions allowed for forgiveness in cases of legitimate emergencies such as official duties, court matters, or medical emergencies, demonstrating a balance between enforcement and empathy.

In ancient times, passing a riding test was no simple feat, as it centered on mastering the art of harnessing livestock and maneuvering carriages. Livestock, with their unpredictable nature, posed a greater challenge to control compared to machines.

Adherence to traffic regulations while riding animal-drawn carts was paramount to ensuring personal safety and the safety of others. The existence of traffic laws and regulations in ancient times mirrors the modern-day emphasis on safe driving practices, highlighting the enduring importance placed on road safety across different historical periods.

(Source: the Paper, China National History)