Henry Chang-Yu Lee, an internationally renowned criminal forensics expert, was born in Jiangsu Province, China, and is of Chinese American descent. In July 1998, he became the chief emeritus for the Connecticut State Police, marking the first time a Chinese American had held such a position at the state level in the United States.

Lee has conducted forensic examinations in several high-profile cases, including the Assassination of John F. Kennedy, the Watergate scandal of Richard Nixon, and the Impeachment of Bill Clinton.

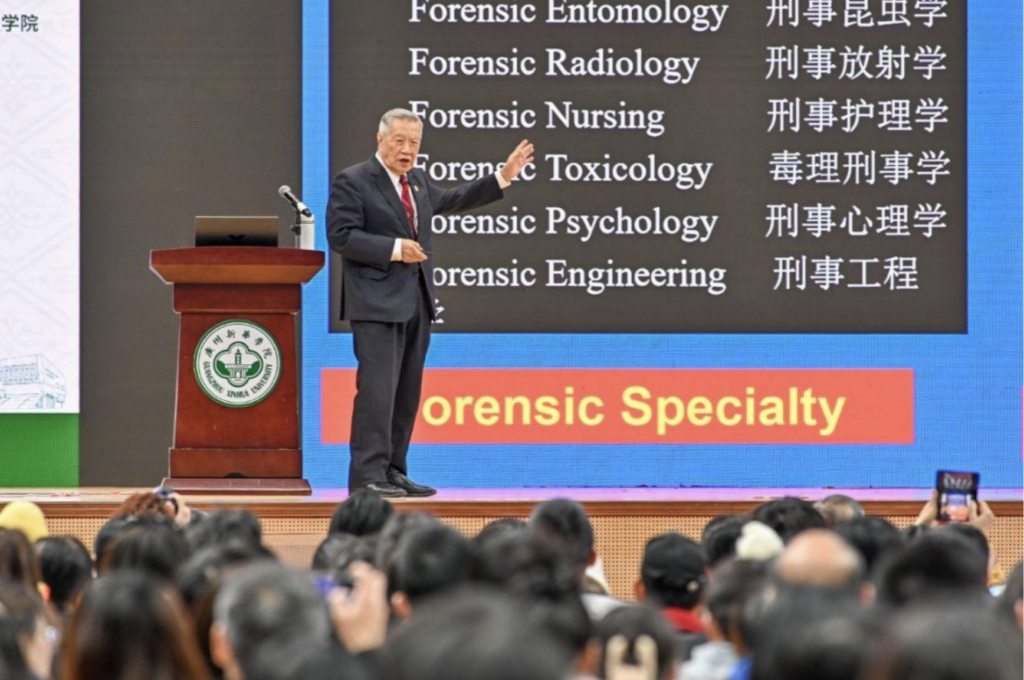

At 86 years old, Henry Chang-Yu Lee remains active and vigorous, speaking with clarity and displaying a keen sense of humor. Recently, he has been extensively involved in activities across China: from attending the opening ceremony of the second phase of the Henry Chang-Yu Lee Criminal Investigation Science Museum in Jiangsu Province, to lecturing at Xinhua College in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, and participating in the charity gala in Shanghai.

With over 60 years of experience in law enforcement, Lee continues to contribute to the exchange and advancement of forensic science between Eastern and Western countries. During his lectures, he captivates young students by sharing intriguing case studies.

Despite his global renown as a criminal forensics expert, Lee humbly stated in a recent interview with China News Agency that he considers himself simply an ordinary scientist. He also encouraged young people to pursue forensic science education.

How has your Chinese background shaped and influenced your career trajectory?

This is a significant and challenging question to address. In the West, due to widespread misinformation perpetuated by the media and society, many Westerners hold the belief that the only contributions Chinese people made to the United States were in building railroads, operating laundries, and restaurants in the 18th century.

Particularly in recent years, Chinese individuals have faced suppressions influenced by social media. However, contrary to these misconceptions, there are numerous outstanding Chinese individuals in the U.S. across various fields who have made substantial contributions not only to the U.S. but also to the world.

Historically, forensic science practitioners in the U.S. were predominantly white men. When I initially applied for membership in the American Academy of Forensic Sciences (AAFS), I faced rejection on the basis of being a person of color, although this information was not accurately assessed. While many Chinese individuals might have tolerated such situations, I took a proactive stance by writing a letter to the AAFS seeking clarification.

The response from the AAFS cited the reason for my rejection as having completed a portion of my educational experience outside the United States. At that juncture, I suggested revising their bylaws to only permit participation from white individuals. Eventually, they granted me provisional membership and awarded me their highest honor after three years.

In 2022, I was invited to speak at the AAFS Annual Conference. During my speech, I emphasized the Academy’s progress over the decades in promoting equality for all members. My hope for the future is one of global peace and integration, envisioning a world where boundaries dissolve, emphasizing our shared humanity, and advocating for equal treatment for everyone.

Which of the over 8,000 cases you’ve handled throughout your career stands out as particularly memorable or impactful to you?

First and foremost, it’s important to dispel any misconceptions: no case can be solved by a single individual alone; it truly takes a team effort. Solving a case involves numerous factors beyond just forensic science; it requires collaboration with criminal police, engagement from the community, and often utilizes large databases and artificial intelligence technology.

It’s crucial to acknowledge that the media’s portrayal can sometimes exaggerate the role of individuals. I don’t consider myself a sleuth akin to Sherlock Holmes or Bao Zheng, a Chinese politician who defended peasants and commoners against corruption or injustice in China’s Song Dynasty; I’m simply an ordinary scientist working alongside others.

When discussing notable cases like the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the murder trial of American football star Simpson, or the Clinton impeachment case, it’s important to recognize that while these cases garnered immense attention due to their high-profile nature, there are countless other cases that are equally significant. One case that has particularly resonated with me is that of the murder of an elderly woman who lived alone. Despite lacking the spotlight, it was a classic case that deeply affected me.

The murder occurred on Thanksgiving, when a concerned neighbor delivered food to the elderly woman, only to discover her lifeless body. She had been brutally stabbed 17 times, and although there should have been ample blood at the scene, the initial responding officers overlooked it.

Through scientific methods, we were able to detect blood on the floor and identify shoe prints. Despite the absence of advanced technology like big data at the time, over 200 officers diligently combed through trash cans near the crime scene that night, eventually leading to a breakthrough. Near the trash cans, we found a suspect who had used a card to purchase the shoes found at the scene — the victim’s nephew, driven to murder due to drug addiction and financial desperation.

There are no rewards or celebrations for solving crimes. However, on that day, we found closure for the victim, prioritized justice, and demonstrated the importance of putting people’s lives first while remaining grounded in reality.

What lessons can Eastern and Western cultures exchange with each other in the realm of forensic science?

Differences between Eastern and Western societies stem from variations in culture and systems, yet the fundamental principles of civilization remain universal. For instance, Chinese learning traditionally emphasizes memorization and recitation, while Western education emphasizes critical thinking. Many Chinese students face challenges when adapting to American culture due to these differences, but fostering open communication can help bridge the gap.

Chinese traditional culture, characterized by the concept of “sincerity,” has deeply influenced my life, emphasizing genuine interactions and actions towards others. Conversely, Western culture, with its emphasis on innovation and breaking rules, has also inspired me significantly.

These cultural disparities often prove beneficial in solving cases. For instance, in a case involving fried chicken found at the crime scene, the manner in which different parts of the chicken were consumed helped determine the perpetrator. I even made a light-hearted remark about Chinese preferences for chicken legs, noting that the untouched fried chicken legs implicated a non-Chinese individual in the crime.

The eclectic nature of Chinese culture influences my approach to interacting with others during investigations. When collaborating with Western counterparts at crime scenes, I employ a peaceful and tactful manner to guide them in recognizing areas for improvement in their forensic skills, fostering a cooperative and productive environment.

Are you familiar with traditional Chinese methods of criminal investigation, and do you believe they remain pertinent in modern forensic practices?

Indeed, the utilization of scientific methods in crime-solving dates back centuries, even to figures like Bao Zheng and Song Ci, a renowned forensic scientist of the Southern Song Dynasty.

Song Ci’s seminal work, “Collected Cases of Injustice Rectified,” is considered the world’s earliest forensic science book. Despite previous beliefs abroad that forensic science originated in England or Austria, Song Ci’s contributions underscore China’s historical prominence in this field.

In contemporary times, China has made significant advancements in criminal investigation, evidenced by the establishment of identification centers within public security systems. Through my experiences teaching and consulting in China over the past few years, I’ve observed firsthand the remarkable progress in forensic science.

China’s forensic science practices now align closely with international standards, with certain aspects even surpassing global benchmarks. This progress highlights China’s commitment to excellence in forensic science and its contribution to the broader international community.

Source: shnewtown, Xinhua, azchinesenews, l-tron