On November 4, Starbucks and Boyu Capital announced a strategic cooperation to form a joint venture that will take over Starbucks’ retail operations in China. Boyu will hold up to 60% of the new entity, while Starbucks retains 40% and continues to license its brand and intellectual property to the joint venture.

Based on an enterprise valuation of approximately $4 billion, Boyu will acquire its stake accordingly. Starbucks expects the total economic value of its China retail business to exceed $13 billion, including proceeds from the divestiture of its controlling stake, the residual value of its retained equity, and long-term licensing income. Both parties plan to expand the Starbucks China network to 20,000 stores, underscoring the strategic importance of the Chinese consumer market to global brands.

With over 150 disclosed deals spanning giants like Foshan Haitian Flavouring & Food, Midea, CATL, iQiyi, and Kuaishou, and with recent purchases such as a 42%–45% stake in Beijing SKP, Boyu Capital has demonstrated a long-standing appetite for high-quality consumer assets.

Only days later, on November 10, CPE Funds reached a similar partnership with Burger King, owned by Restaurant Brands International (RBI). The two sides will establish Burger King China, with CPE Funds injecting an initial $350 million to support expansion, marketing, menu innovation, and upgrades to operational capabilities.

After the transaction, CPE Funds will hold roughly 83%, while RBI retains about 17%. Burger King China will receive exclusive development rights for the next 20 years, and the long-term plan is to expand from the current 1,250 restaurants to over 4,000 by 2035. This arrangement mirrors the broader trend: foreign chains increasingly rely on Chinese capital not merely for financing, but for navigating a market whose scale, complexity, and speed require deep local knowledge.

CPE Funds’ aggressive posture makes clear it is not a passive investor but an operationally active player shaped by China’s consumption upgrading cycle. Established in 2008 as the former CITIC Industrial Investment, with CITIC Securities as its largest shareholder, CPE Funds now manages more than €18.17 billion and has invested in over 300 companies, more than 10 billion of which has gone into consumer services.

Its portfolio stretches from Mixue Ice Cream & Tea and Pop Mart to CATL, Laopu Gold, Yonghe Hair Transplant, and Beauty Farm — touching nearly every aspect of daily life. What sets CPE Funds apart is not breadth but depth: it invests with the intention of reshaping operations, refining strategy, improving management structures, optimizing supply chains, and enhancing marketing execution. Over nearly two decades, it has accumulated resources that are decisive in running large restaurant chains in China — priority access to commercial real estate, sophisticated supply-chain capabilities, and fluency in digital ecosystems such as Meituan, Ele.me, and RedNote.

A wave of foreign food service brand transactions is sweeping through the Chinese market, revealing not only shifting competitive dynamics but also the deepening influence of local capital in the global food and beverage sector.

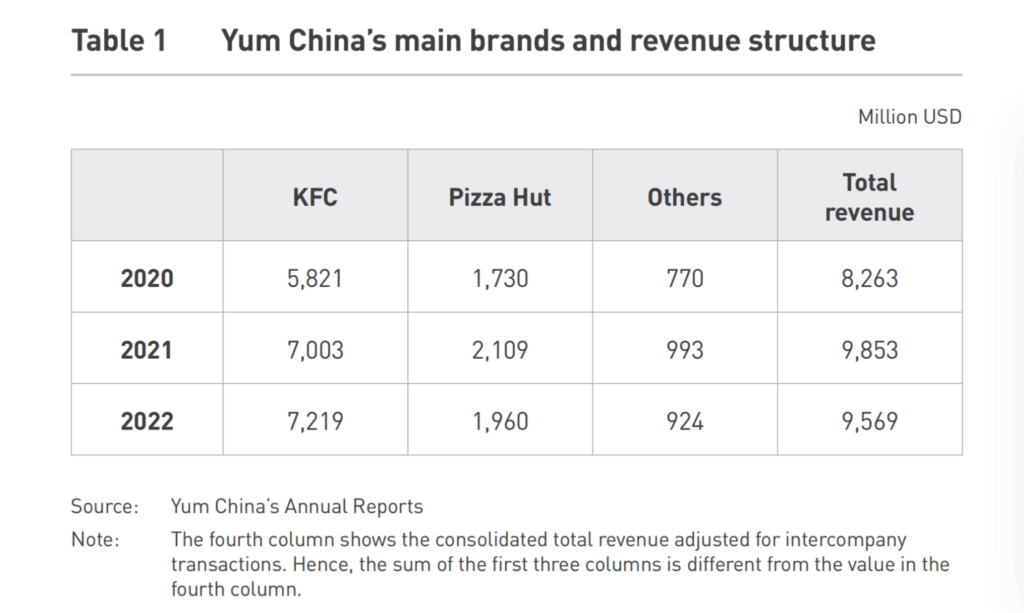

The trend is neither new nor isolated: in 2016, Primavera Capital and Ant Financial invested $460 million in Yum China, which subsequently became the largest franchisee and publicly listed entity operating KFC, Pizza Hut, and Taco Bell in China. One year later, CITIC Limited, CITIC Capital, and Carlyle jointly acquired a majority stake in McDonald’s China.

These transactions are driven by structural changes in the performance of foreign food-service giants. McDonald’s, which operated over 2,400 restaurants in mainland China and more than 240 in Hong Kong before its 2017 sale, had already begun experiencing slowed growth after 2013. Although McDonald’s does not separately disclose China numbers, its financial reports show profits in high-growth markets — including China — declined 5.5% in 2013 and nearly 10% in 2015. Yum China underwent a similar trajectory: after achieving record revenue and profit in 2012, its net profit plummeted by 81% in 2013 and even turned negative in 2014. Though profitability gradually recovered, it never returned to its peak, marking the end of a two-decade expansion cycle.

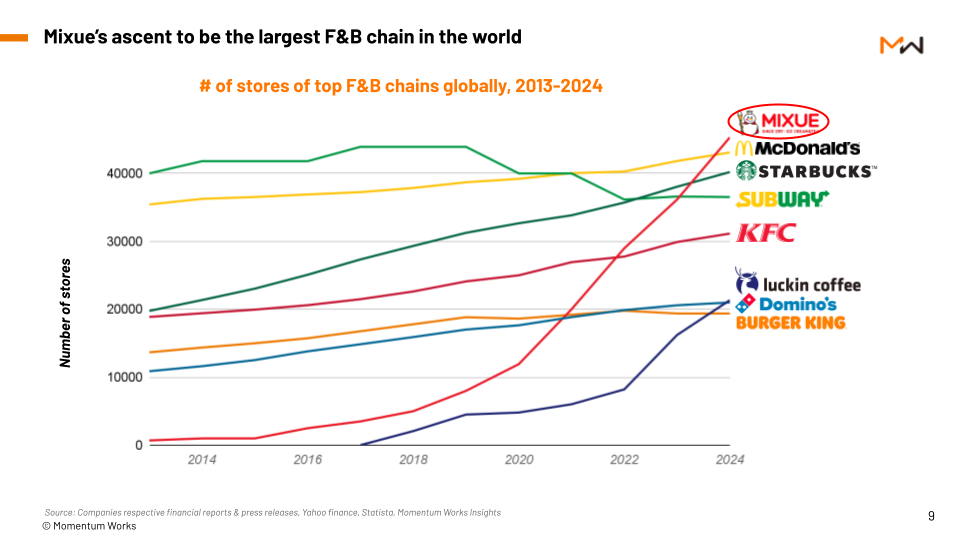

Since then, the pace of China-focused expansion has accelerated dramatically through localized management. McDonald’s China, which took 27 years to open its first 2,000 stores, opened another 5,000 in just eight years, now operating over 7,100 stores and opening two to three new locations daily. Yet this growth highlights how the rules of the game in China have changed. The country’s vast consumer base — with 2024 catering revenue surpassing €665 billion — creates opportunity, but also fierce competition.

Domestic brands in China enjoy advantages that foreign companies struggle to replicate, including China’s uniquely integrated supply chain. Many local chains, such as Kudi Coffee, have already internalized production for nearly all raw materials, drastically reducing costs. Mixue’s vertically integrated supply chain alone produces more than 1.6 million tons of ingredients annually and is expanding into categories like dairy. These capabilities enable local brands to differentiate through pricing, format innovation, and operational efficiency.

The rise of Luckin Coffee illustrates this point. Its shift from large stores to smaller, high-density outlets radically changed the cost structure of the coffee business. Kudi Coffee, founded by Luckin’s original team, now operates over 14,000 stores. With average transaction values around €1.21 to €1.7, compared to Starbucks’ roughly €4.36, domestic brands in China have reshaped consumer expectations. Starbucks has been forced to adopt localized pricing strategies, offering frequent discounts and partnering with platforms to lower effective prices. These changes signal not merely competition, but a fundamental redefinition of the value proposition in China’s coffee market.

Analysts note that foreign brands’ market challenges reflect structural issues rather than cultural barriers. After years of relying on premium locations and higher price points, many international chains saw same-store growth stagnate post-2012 as menus aged, delivery channels disrupted foot traffic, and real estate dividends disappeared. For these companies, introducing Chinese partners means exchanging “future growth options” for “present cash flow.”

Local capital, on the other hand, gains assets it believes it can reposition or scale more efficiently, especially in lower-tier markets where its operational strength is unmatched. Instead of a narrative of “foreign brands failing,” the reality is closer to a mutual risk rebalancing: foreign companies lighten asset-heavy burdens, while Chinese investors take on operational responsibility in exchange for long-term upside.

Local capital taking over foreign restaurant operations generally falls into two categories: real-estate-linked groups which possess powerful property negotiation advantages but lack flagship brands, and private equity firms which seek stable cash-flow stories to support fund operations. Both types leverage China’s regulatory environment, financing mechanisms, and government relationships in ways foreign operators typically cannot. Their ability to package restaurant assets into urban commercial projects or negotiate favorable loan terms gives them a competitive edge in scaling these businesses.

Industry observers also point out that many multinational corporations struggle with China because of centralized global management models. Long decision cycles, rigid procurement standards, and insufficient regional flexibility hinder their ability to respond to China’s fast-paced consumer environment. After localization, McDonald’s China’s management team began reporting to a local board, half of whose members reside in China, enabling faster decision-making. This shift illustrates why many foreign brands now prefer to entrust operations to localized partners who understand policy dynamics, supply-chain structures, and digital ecosystems.

Viewed from a broader perspective, the sale of a foreign brand in China is not the end of its story but the beginning of a new operating model. The future of the Chinese food service market will not be dominated solely by foreign names or purely by domestic brands, but by hybrid structures where international brands provide the global brand power and product systems, and local capital and operators provide the executional muscle and localized strategy.

In the world’s largest consumer market, advantage no longer belongs to whoever has the strongest global brand, but to whoever understands the market’s rules and can move in sync with its pace. Ultimately, doing business in China has never been about what you bring in from the outside, but about what you learn once you are inside.

Source: digitaling, the paper, 36kr, sina finance, ckgsb, thelowdown, yicai