In July 2025, a group of eight senior venture capitalists from leading European and American firms—such as Kompas VC, Planet A Ventures, and Extantia Capital—traveled through China’s eastern industrial belt. Unlike typical investment scouting trips, this journey was not about discovering new opportunities. It was a strategic reconnaissance mission to assess the scale, speed, and technological depth of Chinese clean-tech industries, particularly in batteries, solar, wind, and hydrogen. What they found forced a fundamental reevaluation of their investment theses.

Their visit to CATL’s massive facilities in Ningde, Fujian, delivered the first shock. The factory floors were not bustling with workers but filled with highly automated, silent production lines. Robotic arms handled feeding, welding, assembly, and inspection with a precision and efficiency far beyond what any Western firm had operationalized. This was not just manufacturing scale; it was systematized automation. Moreover, the company’s R&D arm was already presenting near-term roadmaps for solid-state and sodium-ion batteries, backed by engineering timelines and pilot lines already under construction. The gap between aspiration and execution in the West was stark. While European and American firms debated factory locations and environmental assessments, CATL had turned its next decade of battery tech into a production plan.

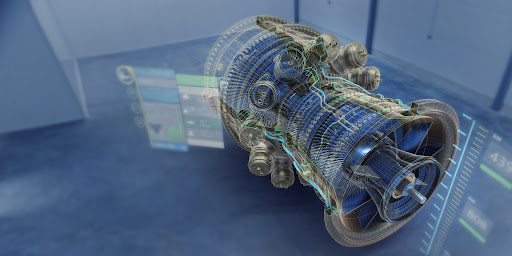

In Shanghai, Marvel-Tech demonstrated a multi-fuel turbine capable of operating on hydrogen, ammonia, and natural gas. What left a deeper impression, however, was the process behind the product. To modify a turbine blade’s curvature, the company required a custom alloy and machining solution. Specifications were sent to a local supplier in the Yangtze River Delta. Within three days, compliant samples were delivered at a cost that astonished the visiting VCs. In Europe, such a request would typically involve weeks of negotiation, high tooling fees, and months of lead time. In China, suppliers function not only as vendors but as collaborative, on-demand extensions of R&D. The agility and affordability of this support system exposed a structural advantage Western ecosystems lack: a manufacturing supply chain that accelerates innovation rather than slows it.

The final leg of the trip took them to Kunshan, where they visited GCL Perovskite’s solar manufacturing facilities. There, they saw perovskite solar modules already on pilot production lines. While this technology remains largely in the laboratory phase in the West, GCL was iterating prototypes on a weekly basis and moving swiftly from research to manufacturing. The speed of commercialization was driven by an unusually tolerant industrial policy environment and a massive domestic market capable of absorbing risk. New materials and processes were validated in real-world conditions within months, not years. Feedback from production was rapidly integrated into further R&D. In contrast, Western companies often face a decade-long cycle of trials, certifications, and capital-intensive scaling hurdles before a product reaches commercial viability.

Returning from the trip, the VCs convened a series of internal reviews. The conclusion was sobering. Several entire sectors were added to a confidential “non-investment list”—segments where Chinese industrial dominance was now viewed as irreversible under current Western conditions. At the top of that list was battery manufacturing and its related supply chains. With Chinese battery costs at roughly $60 per kilowatt-hour—half the production cost in Europe and the United States—competing on price and scale was deemed unrealistic. Adding to the challenge, China controls the processing of most of the world’s critical battery minerals, including lithium, cobalt, and graphite. Attempts to build a Western version of CATL would not only be cost-inefficient but structurally disadvantaged from the outset.

Solar and wind hardware followed. The photovoltaic industry had already shifted dramatically over the past decade, with China now accounting for more than 80% of global solar panel production. The next wave, driven by perovskite and other advanced materials, was clearly underway, and again, Chinese companies were leading in both R&D and industrialization. Wind turbine manufacturing showed a similar trajectory: massive domestic installations had driven down costs while reinforcing heavy industry capabilities that the West had either offshored or allowed to erode. Green hydrogen, specifically electrolyser hardware, was also crossed off the list. China’s combination of subsidies and brutal domestic competition had reduced electrolyser production costs by 30–50% compared to Western firms. For capital-intensive hardware sectors that scale primarily through cost leadership, Western start-ups were no longer considered viable investments.

What struck the investors most was not any individual company, but the collective industrial system. China had built not just factories, but a national mechanism for scaling innovation. This system seamlessly connects research institutions, SME suppliers, engineering talent, capital, and policy support. It embodies what Stanford scholar Dan Wang calls a “scale-before-profit” model, where the goal is not short-term financial return but long-term industrial supremacy. The survivors of this model—companies that endure harsh competition and massive upfront investment—emerge as global champions with unrivaled cost efficiency and execution speed.

For these VCs, the path forward is not protectionism. Tariffs and subsidies may provide temporary relief but cannot reverse the structural disadvantages in scale, speed, and supply chains. Instead, a new paradigm has begun to take shape: “Western Software, Eastern Hardware.” It represents a reallocation of capital from direct hardware competition to software and systems integration—areas where Western firms retain deep expertise and competitive advantage. The logic is straightforward. While hardware’s performance may be fixed by its physical properties, its real-world effectiveness depends on how it’s used, optimized, and embedded in broader systems.

One promising area is software that enhances hardware performance. For instance, better battery management systems can extend battery life significantly through predictive analytics and control algorithms. Another lies in services and business models—deploying Chinese-made hardware through innovative frameworks such as Battery-as-a-Service, or integrating it into intelligent energy networks that manage generation, storage, and distribution. The West can also lead in building global standards, creating platforms for green finance, or designing carbon markets that monetize the decarbonization enabled by Chinese technology. And while China is focused on scaling current technologies, the West can double down on fundamental research: quantum-enhanced materials discovery, AI-driven energy systems, high-end chips, and precision sensors—areas where barriers to entry are high and China’s industrial system has yet to dominate.

Already, capital flows are shifting. At least two European battery start-up investments were paused after the China trip, and a new fund focused on cross-border technological collaboration has been launched. The goal is not to beat China at its own game, but to become the most advanced users and integrators of Chinese hardware.

The broader lesson is that the age of single-point technological advantage is over. Innovation now depends on the systemic ability to scale and commercialize at speed. China’s model, shaped by decades of state-driven industrial policy and relentless iteration, has reached a level of maturity that many in the West had underestimated. For Western entrepreneurs and investors, the imperative is not denial or confrontation, but recalibration. For Chinese innovators, the lesson is equally urgent: hardware supremacy must be followed by leadership in software, services, standards, and global integration.

The global industrial landscape is becoming flatter, faster, and more interdependent. In this environment, neither arrogance nor isolation will succeed. Only clarity of purpose, humility in strategy, and a willingness to collaborate across national and ideological lines will offer a sustainable path forward.

Source: Bloomberg, fujian gov, marvel tech