At the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the nation faced an urgent need to develop its healthcare system. Medical resources were scarce, doctors were few, and medicines were limited.

In this context, the Chinese Communist Party recognized the immense value of traditional Chinese medicine and sought to harness its power to save lives. The ancient remedies, secret formulas, and herbal prescriptions preserved among local communities were not merely cultural artifacts. They were vital tools for preventing and treating illnesses and safeguarding the health of millions.

In 1954, the central government explicitly highlighted that traditional Chinese medicine had played a critical role in the survival and development of the Chinese people for thousands of years, and it was essential to actively explore, preserve, and enhance this medical heritage.

In the years that followed, local party committees mobilized communities to collect these folk remedies. What began as a modest effort to gather useful medical knowledge gradually transformed into a nationwide movement. Collecting these remedies was not only a matter of preserving a medical tradition and protecting public health; it was also a step in the broader project of modernizing the nation.

Yet, while recent scholarship has often focused on the contributions of individual doctors, little research has examined the political and social framework of this initiative, or how the government organized and promoted it across the country. Understanding these dynamics provides insight into the intersection of healthcare, politics, and nation-building in early PRC history.

The collection of folk remedies was deeply intertwined with the principles guiding China’s early healthcare policy. The nation faced severe public health challenges: infectious diseases, parasitic infections, and endemic illnesses such as plague, tuberculosis, schistosomiasis, and goiter threatened millions of lives.

Meanwhile, the country’s medical infrastructure was weak, and the domestic production of chemical medicines was insufficient. To address these issues, the government established four guiding principles for healthcare: prioritize workers, peasants, and soldiers; focus on prevention; unite Chinese and Western medicine; and combine healthcare work with mass mobilization. These principles laid the foundation for a healthcare system that could leverage both scientific and traditional knowledge while engaging the population in active public health efforts.

Despite these policies, the principle of uniting Chinese and Western medicine initially received little attention. It was not until Chairman Mao, in June 1954, emphasized the importance of strengthening traditional medicine that the health authorities began to take it seriously. By July, the Ministry of Health issued its first official report on developing Chinese medicine, outlining a systematic plan to collect, verify, and study folk prescriptions.

The government aimed to preserve these formulas, assess their effectiveness, and integrate them into broader medical practice. Shortly thereafter, state newspapers encouraged Western-trained doctors to study traditional medicine, reinforcing the political and scientific importance of the initiative. With these directives, folk remedy collection became a matter of national significance, driven by top-down organization and leadership.

To support this effort, the government established specialized research institutions. Mao instructed the immediate creation of Chinese medicine research centers to recruit skilled practitioners and preserve their knowledge. By late 1955, the Ministry of Health had founded the National Institute of Chinese Medicine in Beijing.

Beyond the national level, provincial and local institutions were established to expand the reach of this work, creating a network of research centers, hospitals, and universities dedicated to collecting and studying traditional remedies. By the early 1960s, almost every province had its own research institute, forming the backbone of a nationwide effort to safeguard China’s medical heritage.

The initial phase of remedy collection was deliberate and structured. In 1954, regional and provincial meetings of traditional medicine representatives began sharing clinical experiences and testing effective remedies. Gansu Province collected over 800 prescriptions in a single year, while Fujian, Hebei, Henan, and Yunnan provinces compiled thousands more. These early efforts were largely limited to licensed practitioners and scholars, but they established models and methodologies that would later support mass participation.

By 1958, the campaign entered a new stage, evolving into a nationwide movement with mass involvement. National conferences on medical technology and Chinese medicine advocated public participation in collecting and documenting folk remedies.

Hebei Province set an early example, organizing a “people’s collection” campaign with the slogan: “Everyone contributes, everyone discovers, unearths everything from the people.” Within weeks, over 160,000 remedies were gathered, inspiring other regions to follow suit. State media amplified this call to action, framing the initiative as a patriotic duty and a practical contribution to public health.

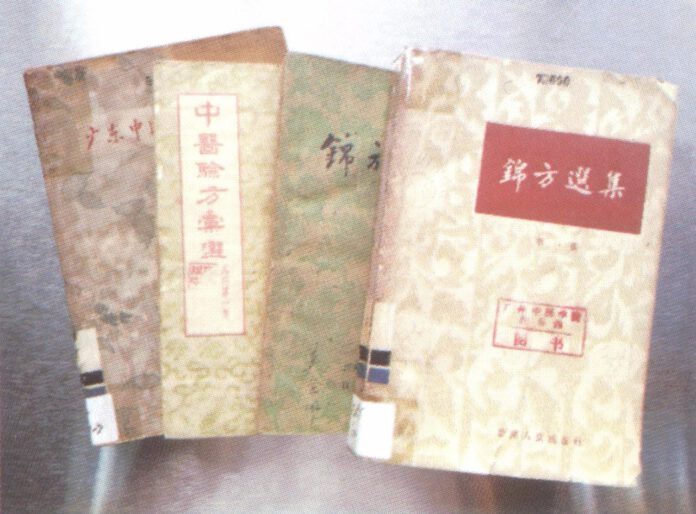

Communities across China embraced the movement. In Shaanxi, local authorities organized public gatherings to encourage citizens to share remedies, while Henan collected over a million prescriptions in a single year. Hebei produced “One Hundred Thousand Golden Prescriptions,” documenting traditional remedies for acupuncture, infectious diseases, and other common ailments.

Shanghai, Hunan, Guangdong, and Fujian provinces also launched large-scale campaigns, compiling hundreds of thousands, and in some cases millions, of remedies. Even industry and transportation sectors, such as the railways and pharmaceutical companies, joined the effort, collecting and verifying prescriptions with impressive dedication.

The results of this mass movement were profound. First, it significantly improved public health. Countless remedies addressed a wide range of conditions, from parasitic infections and snakebites to injuries, fractures, epilepsy, and influenza. In 1956, a team treating schistosomiasis in Wuhan successfully alleviated abdominal swelling in thousands of patients using locally collected formulas.

In Nantong, Jiangsu, a physician’s specialized anti-snakebite remedy became widely applied, while in Hebei, acupuncture and herbal remedies helped curb influenza outbreaks. In Fujian, practitioners successfully treated over a hundred severe burn cases using traditional formulas. These practical applications demonstrated the tangible health benefits of integrating folk knowledge into public health.

Second, the campaign played a critical role in preserving and modernizing China’s medical heritage. While traditional medicine had a rich history of empirical success, it lacked systematic scientific frameworks. By collecting and studying these remedies, researchers could analyze and document their efficacy, refine formulations, and eventually integrate them into modern medical practice.

This process not only strengthened the scientific understanding of Chinese medicine but also ensured that its valuable knowledge was transmitted to future generations. The National Institute of Chinese Medicine, for example, selected hundreds of remedies for compilation, testing, and clinical application, laying the groundwork for what would eventually become a modernized and scientifically informed Chinese medical system.

Finally, the movement fostered a sense of national pride and loyalty. Physicians and ordinary citizens alike contributed remedies out of gratitude and civic duty, motivated by a desire to serve both their communities and the nation.

Many practitioners gained recognition and were elected to governmental and advisory positions, further integrating traditional medicine into the fabric of the state. Stories of individuals offering multi-generational family formulas illustrate how personal dedication intertwined with national purpose, reflecting the broader societal mobilization characteristic of early PRC initiatives.

The collection of folk remedies in the early years of the People’s Republic was far more than a medical exercise. It was a carefully orchestrated national campaign that combined political guidance, grassroots participation, and scientific inquiry.

It strengthened public health, preserved a rich medical tradition, advanced the modernization of Chinese medicine, and cultivated a sense of civic responsibility and patriotic commitment among practitioners and the public alike. This remarkable chapter in China’s history demonstrates the power of cultural heritage, political organization, and mass mobilization coming together to serve the people and the nation.

Source: zzxk, baidu, zhihu, yizhe dum, njucm