On December 13, 1937, 27 Westerners witnessed the atrocities committed by the Japanese army in Nanking when it seized the city. Five of whom were from Germany, all of whom contributed in varying degrees to the protection of the refugees. During the Nanking Massacre, Christian Jakob Kröger, an engineer with the Nanjing branch of the German merchant firm Carlowitz & Co, served as treasurer of the International Committee and was responsible for financial matters. At the same time, he helped to establish a Red Cross hospital for wounded Chinese soldiers, transported food for the refugees, drove away Japanese soldiers who raped women, and tried to protect the refugees. What is even more worthy of our respect is that he left behind for posterity a number of written materials that bear witness to the atrocities committed by the Japanese.

On January 23, 1938, he was finally allowed to leave for Shanghai by taking a Japanese military train, accompanied by Japanese gendarmes. He was the first Westerner to leave Nanking. During his week-long stay in Shanghai, he gave lectures on the situation in Nanking and on Japanese atrocities.

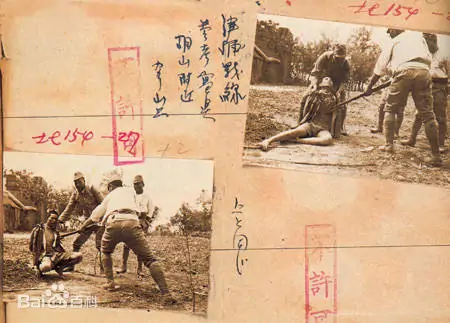

Kröger recorded the cases he witnessed, which were included in the documents of the Nanking Safety Zone. For example, in Case 185: “On the morning of January 9, Mr. Kröger and Mr. Hase saw Japanese officers and a Japanese soldier execute a poor man dressed in civilian clothes in a small pond on Shanxi Road, east of the Sino-British Cultural Building, within the security zone. The man was standing waist-deep in the water of the pond, with freshly broken ice floating around on the surface, when Mr. Christian Jakob Kröger and Mr. Hase arrived. The Japanese officer gave the order and the soldier crawling behind the sandbags fired at the man, hitting him in the shoulder. He fired another shot and missed. The third shot killed him.”

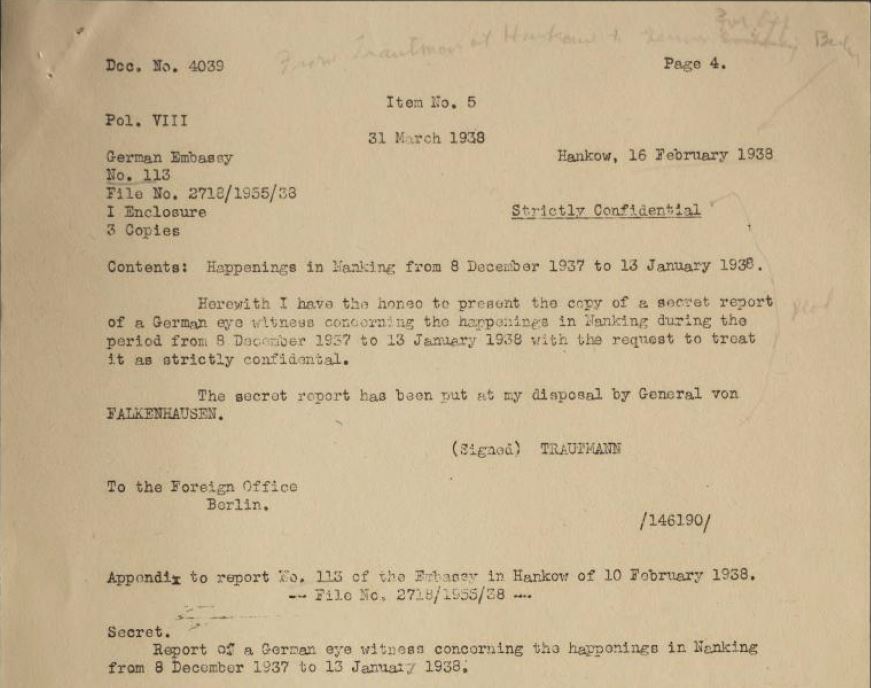

During the Nanking Massacre, in addition to documenting these specific atrocities, Kröger also wrote and sent letters promptly about the entire city under the ravages of the Japanese: the atrocities committed by the Japanese, the damage to German property, the relief efforts for the refugees, and the conditions in the towns and villages of Nanking. His letters were forwarded to the German Foreign Office by Martin Fischer, the German Consul General in Shanghai at the time, and by Oskar Paul Trautmann, the German Ambassador in Hankow, which can be seen today in the archives of the Foreign Office in Berlin.

Kröger’s most influential testimony was his lengthy “Report of a German eyewitness concerning the happenings in Nanking from 8 December 1937 to 13 January 1938”. After the war, during the trial of Japanese war criminals before the International Far Eastern Military Tribunal from 1946 to 1948, the German report was translated into English by the Allies and admitted by the prosecution as witness evidence and numbered Doc. No.4039 along with John Rabe’s letter of January 14, 1938, and submitted as Exhibit No.329. On August 30, 1946, the prosecutor, U.S. Attorney David Nelson Sutton, read most passages of the report, including those describing the burning and killing, at the trial of Iwane Matsui before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

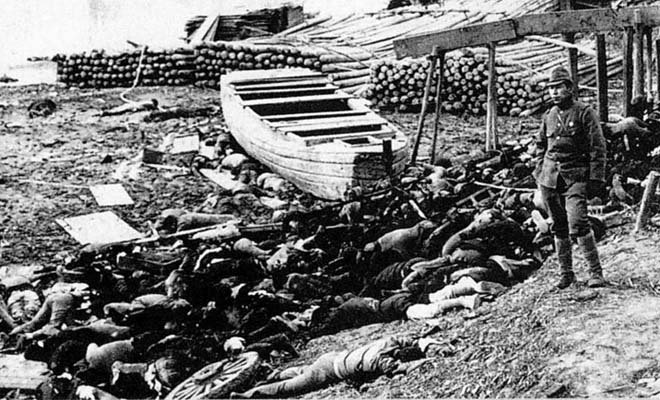

“The picture of the city has changed completely under Japanese rule. No day goes by without new cases of arson…one could say that 30 to 40 percent of the city has been burned down…Although no shot was ever fired on the Japanese by the Chinese in the city, the Japanese shot dead at least 5,000 men: mostly at the river, so that one could forgo the burial…Another sad chapter is the maltreatment and violating of many girls and women. Unnecessary barbarities and mutilation, even on small children, are not uncommon…”

Almost 50 years after the Nanking massacre, Kröger, who was 83 years old and living a quiet retirement in Hamburg, was aware that the 50th anniversary of the Nanking massacre was approaching. The unbearable images of the past flashed back into his mind. Once again, he retrieved the long article with the title “Die Schicksalstage von Nanking” (Days of Fate for Nanking), revised it, and reprinted it.

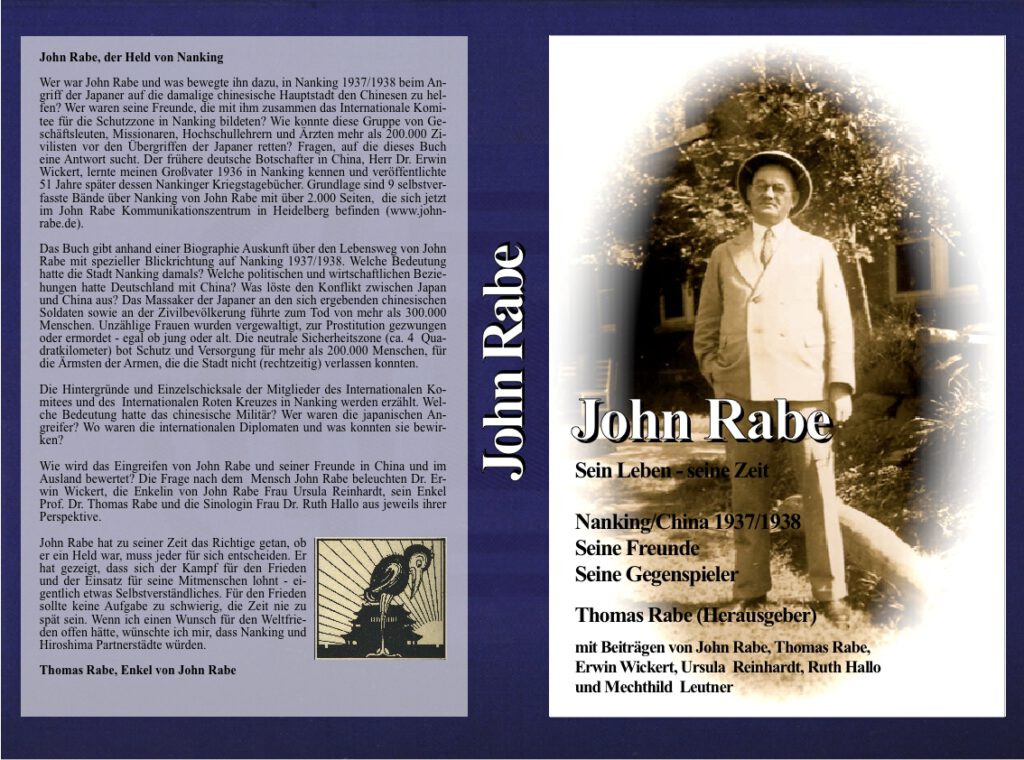

On January 4, 1986, he wrote an addendum to the reprinted report: “This account of the fateful days in Nanking, which the world press has since dubbed the ‘Nanking Atrocities,’ was rarely mentioned in the German press at the time, as there was a friendship pact between the Japanese and Hitler governments, and this type of information would have interfered with that pact. This account was circulated in Germany only among a very small circle of people, and among my relatives. My friend, John H. D. Rabe of the Siemens Foreign Office, who was then president of the committee, was arrested and detained for a long time in Berlin while giving a lecture. When I returned to Germany, I did not follow his example, despite the great demand for Nanking news…At the end of January 1938, I left Nanking by train and soon went to Hong Kong, where I got married and where my eldest son was born. At the end of January 1939, I left China forever, for which I deeply regretted and still regret. Whether this story appeared in the press or not I don’t think is important.”

On February 2, 1986, he mailed this newly printed report to Guo Fengmin, then the Chinese ambassador to Germany. In his letter to the ambassador, he wrote: “Your Excellency, in view of the approaching 50th anniversary of the Japanese capture of Nanking, I have to present, as a stranger, the material recorded on January 13, 1938. I was then a member of the International Committee for the Nanking Refugee Zone. This record was never published and was only known to a small extent at the time because the political situation in 1938 did not allow it to be published. I believe that these events of 1938, which the world media called the ‘Nanking Atrocities’, should not be forgotten. Dear Mr. Ambassador, these records are yours to use in any way you see fit.”

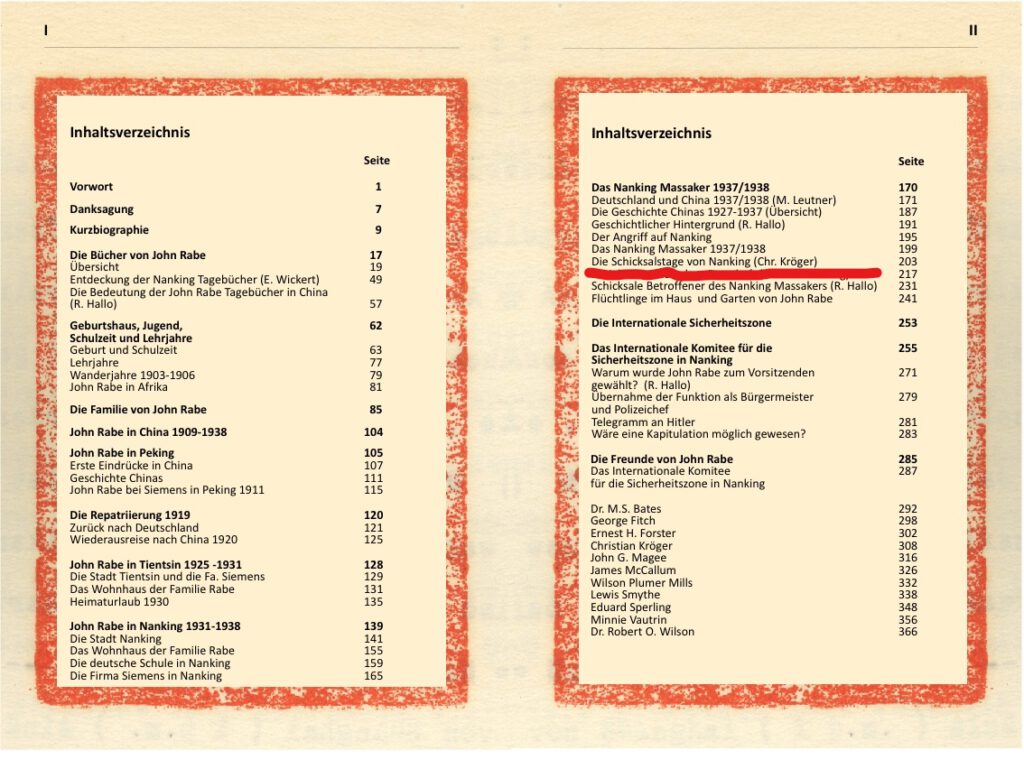

After Kröger’s death on March 21, 1993, his eldest son, Peter Kröger, found this eyewitness report on his father’s desk. In 2009, Thomas Rabe, John H. D. Rabe’s grandson self-published a collection of essays in memory of his grandfather, “John Rabe. Sein Leben, Seine Zeit” (John Rabe: His Life, His Times). The full text of the 1986 edition of “Die Schicksalstage von Nanking” (Days of Fate for Nanking) and its addendum is included. This time, Kröger appears at the bottom of the title of the eyewitness report and the end of the addendum.

At the time of the Nanking Massacre, Kröger was 34 years old. He had the energy to travel around the city and beyond to find out what was going on. He was actively involved in setting up the Red Cross hospital at the Foreign Office to house wounded Chinese soldiers; negotiating with the Japanese for more food for the refugees; patrolling the security zone to stop Japanese violence as much as possible, especially to drive away Japanese soldiers and protect women more effectively.

Thanks to his work and activities, which he actively carried out despite the horror, he had numerous opportunities to witness and observe the Japanese atrocities and the suffering of the citizens of Nanking at close quarters, and thus wrote a 14-page eyewitness report, which not only expressed his anger and reported the situation in Nanking and the Japanese atrocities to the German authorities, but also revealed the truth that the Japanese authorities tried to cover up, and left a valuable first-hand account for future generations. He also revealed the truth that the Japanese authorities were trying to cover up, leaving valuable first-hand primary sources for future generations of scholars to objectively examine that unpleasant period in history.

(Source: John Rabe Page, University of Virginia School of Law, The 1937 – 1938 Nanjing Atrocities, John Rabe’s Nanjing Diaries, baidu)