The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is now four years old. The regulation which originally came into effect on May 25, 2018, provides strict guidelines for the protection and management of personal information for EU citizens and applies to any company that processes data of EU citizens, regardless of the company’s location.

Four years on, this world’s leading data law has certainly changed the way businesses operate, but its effect on the tech giants remains quite limited.

Ineffective rulings

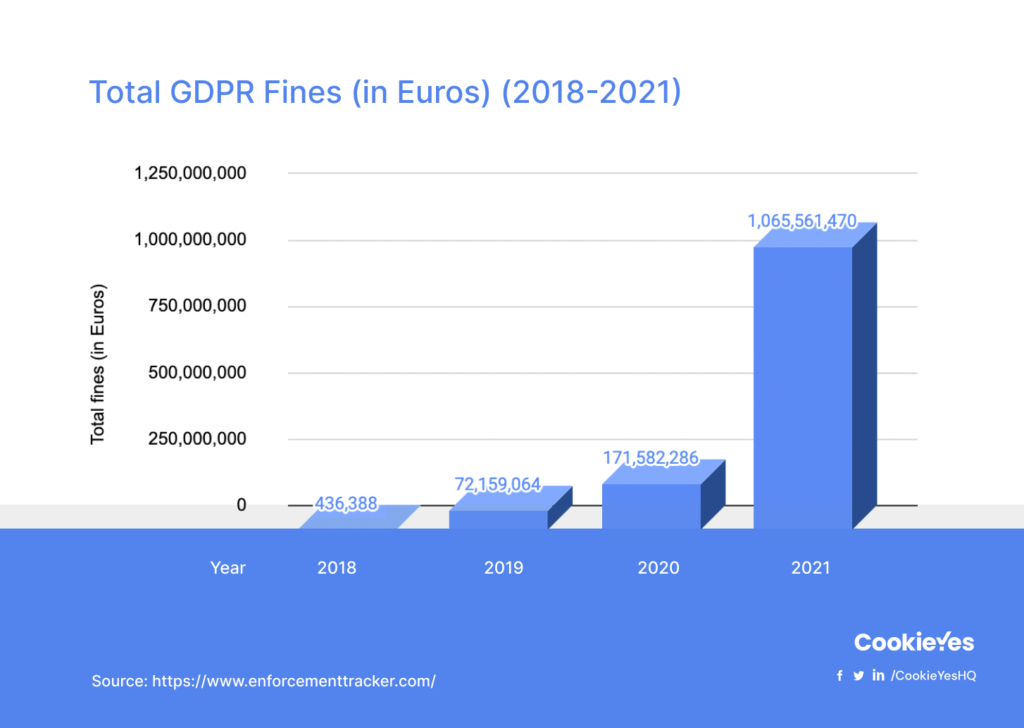

In terms of implementation, the total number of GDPR rulings against major data companies around the world remains very low.

For example, more than 1,400 days have passed since the nonprofit data rights group NOYB launched its first lawsuit under the GDPR. These allegations are primarily against well-known vendors, including Google and Facebook, because they forced users to give up their personal data without their proper consent. The historic complaint appeared on May 25, 2018, the day the GDPR went into effect, but four years later, NOYB still hasn’t waited for a final judgment

Under the GDPR, when a company operating in each EU country/region receives a lawsuit, the case is usually transferred to the country/region where its European headquarters are located. For example, the lawsuit against Amazon fell on Luxembourg; the Netherlands is dealing with Netflix; Sweden has Spotify; Ireland has the relatively heavy task of taking care of Meta, WhatsApp, Instagram, Google’s services, Airbnb, Yahoo, Twitter, Microsoft, Apple, and LinkedIn.

A large number of complex early GDPR proceedings have already put enormous pressure on the Irish regulator, and cross-border collaboration has been slowed by cumbersome paperwork. According to the regulator’s own published statistics, since May 2018, the Irish regulator has completed 65 percent of cross-border adjudication cases, with 400 cases pending.

Experts believe that without the GDPR in place, companies will continue to misuse people’s data with the same reckless abandon as before. A recent study estimates that the number of Android apps in the Google Play Store has dropped by a third since the GDPR came into being, citing the failure of this downgraded software to effectively protect user privacy.

Tech companies struggle to comply

As things stand, Meta is still having trouble complying with GDPR, and an internal Facebook document obtained by Motherboard, for example, suggests that the company itself isn’t quite sure how it handles user data.

According to Facebook engineers, they are trying to keep track of where user data goes in their systems. However, regulations such as GDPR limit how platforms like Facebook can use their users’ data, and the GDPR law states that personal data must be collected for specific, explicit, and legitimate purposes and must not be further processed in a way that is incompatible with those purposes.

Facebook has been criticized for using its users’ phone numbers in its “People You May Know” feature. After being caught, the company eventually had to stop the practice.

Similarly, in a joint investigation in late 2021, the websites WIRED and Reveal found serious flaws in the way Amazon handled customer data.

According to Ulrich Kelber, Federal Commissioner of Germany’s Data Protection and Freedom of Information, the GDPR is still struggling to regulate large technology companies. After all, the cases of large technology companies certainly involve cross borders, which requires cooperation between multiple data protection authorities through a one-stop mechanism.

Changing the way the GDPR works

Four years after, the GDPR itself has revealed many parts that need improvement. Tobias Judin, head of the International Section at the Norwegian Data Protection Authority, mentioned that they need to circulate several draft rulings each week among the various European data regulators. These rulings often require multiple trips between regulators, during which they are also heavily influenced by bureaucratic habits. It should be considered whether the current approach of having a single data protection authority in one country responsible for handling cases affecting multiple European countries simultaneously makes sense and is feasible.

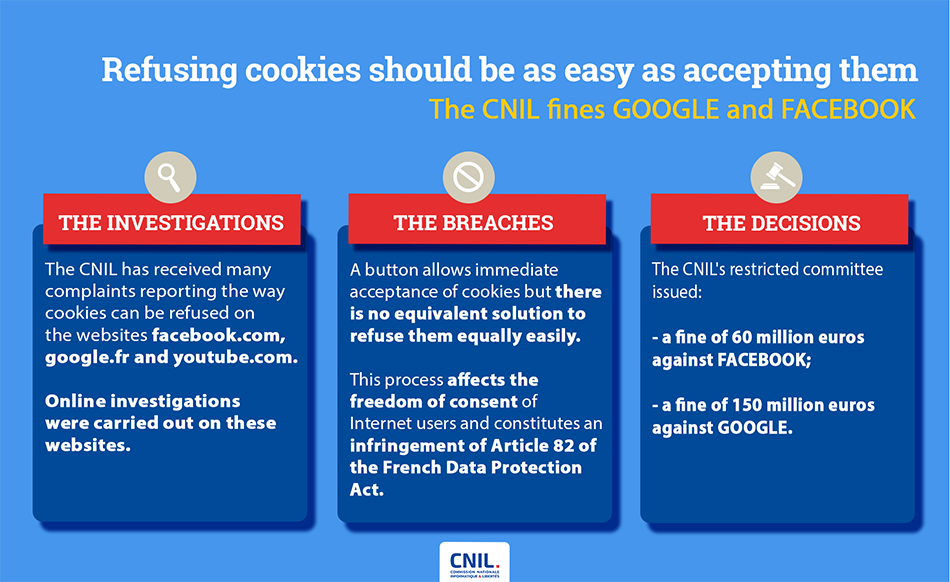

The French data regulator, for its part, prefers to go directly after companies for how they use cookies, thereby bypassing the cumbersome cross-border GDPR process. While it may seem like the same thing, the pesky cookie window is not governed by the GDPR, but by the EU’s separate e-Privacy Act. France saw this coming, and Marie-Laure Denis, the head of its regulator, CNIL, has proposed huge fines against Google, Amazon, and Facebook for their cookie policies. More importantly, the case has caused the big players to change their behavior. In the wake of this enforcement, Google changed its cookie prompting style across Europe.

Denis explained that the CNIL will next look at how to manage data collection on mobile apps under the ePrivacy Act and cloud data transfers under the GDPR. She believes that the cookie breakthrough is not simply an attempt to avoid the lengthy process of the GDPR, but rather an attempt to effectively address the problem.

Calls for changes to the way the GDPR works have grown in the last year. Viviane Redding, a politician who proposed the GDPR in 2012, spoke on the topic last May, stating that for big things, enforcement should be more focused. In response to the call, Europe has adopted two more major digital regulations: the Digital Services Act and the Digital Marketplace Act. These laws focus more on competition and Internet security and are enforced in a different way than the GDPR. In some cases, the European Commission will directly investigate large technology companies. From this perspective, GDPR enforcement does seem to be out of step with the mainstream and reinforces the inefficiency of enforcement previously raised by politicians.

Potential improvements

Redesigning the GDPR doesn’t seem necessary, but a few minor tweaks might help improve enforcement. At a recent meeting of data regulators held by the European Data Protection Board, countries agreed to set fixed deadlines and timelines for some cross-border cases and said they would work to “join forces” on certain investigations.

Massé from Access Now said that a small change to the GDPR would be enough to significantly improve some major enforcement challenges today. Legislation should be passed to ensure that data protection authorities use the same way to handle complaints, specify how the one-stop-shop mechanism will work, and ensure seamless integration between national/regional protocols. In short, it should at least clarify how GDPR enforcement should be implemented in each country.

Dixon, from Ireland, also stressed that it should be better if specific legal instruments are issued for the GDPR, specifying certain processes and procedural issues. She added that the new rules should also respond to issues such as access to documents during investigations, whether the plaintiff side of the lawsuit has the right to participate in the investigation, and the manner of translation.

Civil society groups have also warned that without some strong enforcement changes, GDPR may ultimately fail to stop the egregious practices of large tech companies, let alone raise awareness of privacy.

(Source: wired, VentureBeat, vice, forbes, cookieYes, CNIL)