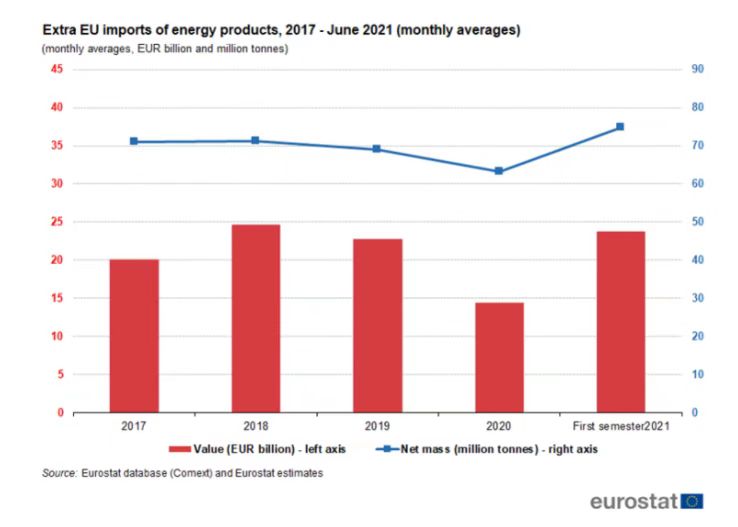

Western Europe, as one of the most economically developed regions in the world, has a huge demand for oil and gas for daily life and economic development. However, due to the uneven distribution of energy in the world, the oil and gas resources in Western Europe are particularly scarce compared to the demand, and relevant data show that the EU significantly relies on imports of energy over years.

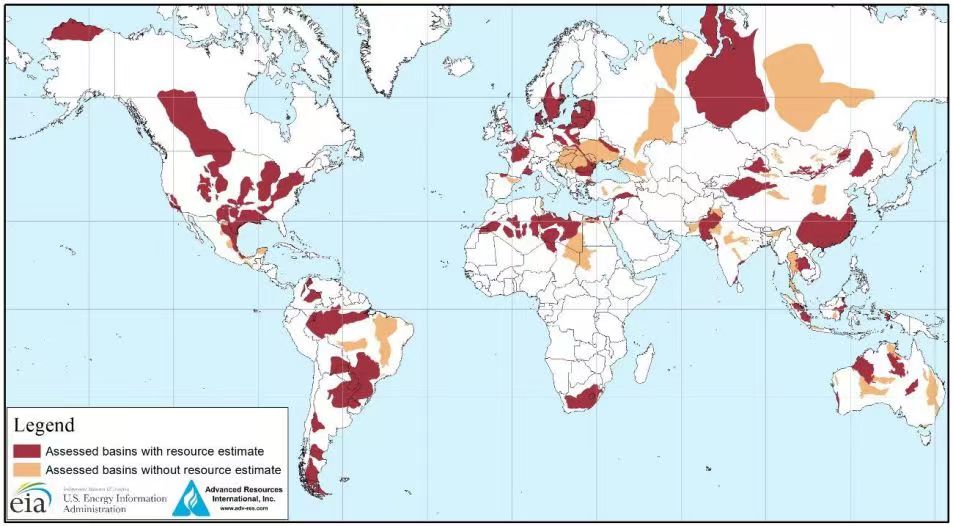

In sharp contrast to Western Europe, Russia is rich in natural energy reserves, ranking eighth in the world for oil reserves and first in the world for natural gas reserves, according to 2018 data from the U.S. CIA. The abundance of natural resources has given Russia a material basis for a well-developed oil and gas industry and has provided a major energy supply channel for Western European countries.

Energy diplomacy between the EU and Russia

The history of energy cooperation between EU countries and Russia is quite long, as early as the 19th century, Tsarist Russia had exported oil to Europe. Since the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the socialist countries of Eastern Europe have been actively cooperating in energy and building gas pipelines. Even Italy and Austria in the capitalist camp signed oil and gas trade contracts with the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s, despite the opposition of Britain and the United States.

When the oil crisis broke out in the 1970s, the economic environment of the oil embargo adopted by OPEC, which led to the rise of oil prices, seriously affected the energy supply of the Western European countries. As a result, the Western European countries had to put aside their ideological disputes and chose to import oil and gas resources from the Soviet Union, making the Soviet Union a new partner of European countries in the oil and gas trade at that time.

On the other hand, Yeltsin’s pro-Western policy in the 1990s also furthered Russia’s energy trade relations with Western European countries. Moreover, since the beginning of the 21st century, the EU’s increasingly stringent ecological standards, especially concerning harmful substances in petroleum products and gas emissions, have greatly affected the EU’s oil imports, making natural gas a major source of energy in everyday life, and Russia is the country with the world’s richest natural gas reserves.

Plus, Russia also needs to trade energy to drive domestic economic growth, and the existence of a stable, long-term energy trade export partner is particularly necessary for it.

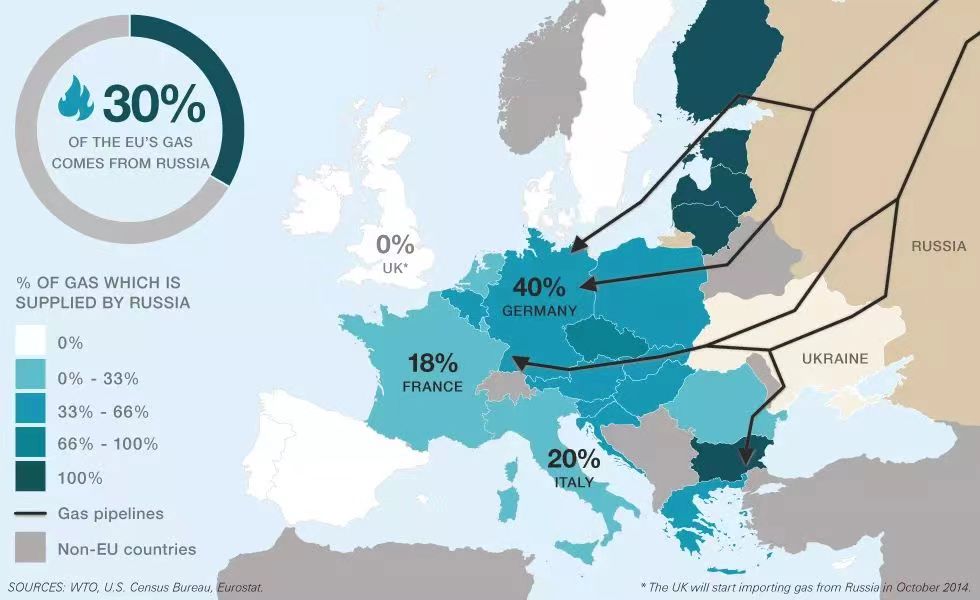

For all these reasons, Russia’s oil and gas exports match the EU’s market demand, and the highly complementary energy strategies of both sides lay the foundation for long-term European-Russian cooperation. In particular, Germany, Finland, Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and other countries, which are located in the middle of Europe and have difficulties in obtaining oil and gas resources from North Africa and the Middle East, are unable to get rid of their dependence on Russian oil and gas.

Russia’s Oil and Gas Industry Boom

Russia’s oil and gas resources are favored by Western Europe not only because both sides take what they need, but also because of Russia’s well-developed oil and gas industry system.

Russia has been developing its oil and gas industry since the Soviet era. Since most of Russia’s natural resources are located in the less developed eastern part of the country, while most of the heavy industries are located in the western part of Russia, the inconvenient transportation conditions have led to a significant increase in the cost of oil and gas transportation.

To meet the demand for oil supply, the Soviet government quickly built the Trans-Siberian Railway and established a one-stop industrial system from oil and gas exploration to development, processing, and transportation, which made the oil and gas industry the second-largest refining capacity in the world after the United States by the 1980s.

Starting from the end of 20th century, the world crude oil prices rose, Russia’s share of crude oil, natural gas, and refined oil exports in exports increasing from 28.4 percent in 1992 to 50.8 percent in 2000, and by 2018, Russian oil exports had accounted for 12.8 percent of total global exports that year, while natural gas accounted for 26.3 percent.

With oil exports becoming the core of Russia’s foreign exports and the country’s fiscal balance becoming increasingly balanced, Russia, in this more stable economic environment, has also proposed the idea to use the ruble as oil settlement currency. In 2006, Putin officially announced that Russia would sell energy in rubles in an attempt to further control the energy market.

Russian oil and gas companies have adopted the model of providing oil and gas – joint venture – holding in cooperation with neighboring countries, and they controlled the oil supply and terminal sales markets in CIS, Baltic sea and Eastern European countries by 2007.

European resistance to dependence of Russian energy

But there are always countries that refuse to let their energy markets be completely controlled by others, and Ukraine is the most typical case of resistance to Russia’s energy power.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia had to pay the Baltic sea states and Ukraine exorbitant annual gas transit fees, so when Russia followed its control of most of Ukraine’s refineries and oil sales, it started to use pipeline control as its main energy diplomacy tool, trying to force Ukraine to cede control of gas pipelines by rising gas prices.

On the other hand, Ukraine’s unfavorable economic development has led to a growing gas debt to Russia, which by 2014 had reached $5.3 billion. Faced with the growing debt and Russia’s price hikes, Ukraine has responded by raising gas transit fees. And for Ukraine, once the gas pipeline was fully in Russia’s hands, it would be tantamount to having its economic lifeline completely contained, something the nation could never accept.

Three major gas trade conflicts erupted, and at one point Russia cut off gas supplies to Ukraine as a means of forcing it to make concessions.

Russia’s monopoly in the European gas market has gradually formed, and the EU’s energy supply security has come into question. To reduce its overdependence on Russian gas, the EU has been working for nearly a decade to increase the market share of non-Russian energy companies in Europe and seek diversified gas sources to gradually dilute the monopoly of Russian gas on the European market.

As Russia considers Central Asia and the Caspian region as its belongings, it is trying to prevent Central Asian gas from entering the European market directly. To allow Central Asian gas to enter the European market directly and compete with Russian gas, the European Union has started the construction of gas pipeline projects bypassing the Caspian region, in an attempt to change the status quo of the EU’s heavy dependence on Russian gas.

Since the “shale gas revolution” in this century, the U.S. has gradually achieved self-sufficiency in energy supply, and the natural gas originally needed to be delivered to North America can now be shipped to Europe, which also gives the U.S. natural gas the ability to compete with Russian gas in the European market and become major leverage in the EU’s negotiations with Russia.

The EU also launched antitrust investigations against Gazprom, and the two sides eventually reached a settlement in which the EU did not issue an astronomical fine, but Gazprom did make significant concessions, thus showing that the EU still cannot completely get rid of its dependence on Russian gas.

Russia, hit by both the “shale gas revolution” and the “Ukraine crisis,” has had a much harder time than before. But till now, Russia is still the EU’s largest energy importer. Securing a stable supply of oil and gas resources is a major focus for the EU countries to achieve socio-economic development, so Russia can be said to control the energy lifeline of the Western European countries to some extent.

Although Russia’s cut-off of gas supplies will undoubtedly cause fierce social unrest in European countries, Russia does not dare to completely abandon the European market, because that would be a major shock to its economy. Interestingly, this dilemma arises from the common choice of Europe and Russia.

(Source: eurostat, eia, wikipedia)