France’s conquest of Vietnam, despite being a distant European power, is a story that intertwines missionary activity, opportunistic diplomacy, and the gradual weakening of China’s traditional tributary system. For centuries, Vietnam, Korea, and the Ryukyu Kingdom were loyal tributaries of the Qing Dynasty, closely tied to the central empire and participating in its ancient diplomatic network.

Yet by the late 19th century, all three had fallen under foreign domination: Korea and Ryukyu to Japan, and Vietnam to France. While Japan’s imperial expansion in East Asia is widely known, the mechanisms by which France, thousands of miles away, gradually seized Vietnam remain less clear, yet are equally instructive.

The roots of French influence in Vietnam can be traced as far back as the late 17th century, when French missionaries arrived in the country under the guise of spreading Catholicism. Vietnam’s economy at the time was stagnant, and the rural population endured extreme poverty. Missionaries capitalized on this vulnerability, promoting the ideals of charity and “universal love,” offering education, medical care, and social assistance.

Their work quickly embedded them in local communities, laying the groundwork for a far broader influence. By the mid-18th century, France had identified Vietnam as a potential target in its overseas colonial strategy. Missionaries—long serving as the vanguard of French intervention—began gathering intelligence, cultivating networks among local elites, and preparing the logistical and informational groundwork for a future incursion.

A fortuitous opportunity soon presented itself. In 1777, Vietnam descended into internal turmoil when a king was assassinated, forcing Prince Nguyễn Phúc Ánh to flee to Saigon, where he found refuge with French missionary Joseph Pétard. Recognizing the strategic opportunity, Pétard advised Nguyễn Phúc Ánh to seek French assistance to reclaim his throne. The French, eager for influence in Southeast Asia, responded swiftly. In October 1787, France and Vietnam signed a treaty in Paris—the Treaty of Versailles—where King Louis XVI pledged to assist Nguyễn Phúc Ánh in restoring his rule. In return, Vietnam agreed to lease the port of Da Nang to France, allowing French warships to dock, developing trade infrastructure, and granting exclusive rights for missionary work.

The outbreak of the French Revolution shortly thereafter disrupted these plans. With France preoccupied, Pétard personally financed a mercenary force to support Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, who, doubting French reliability, ultimately sought assistance from the Qing Dynasty. With Qing military support, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh successfully restored order by 1803, founding the Nguyễn dynasty and inaugurating the Gia Long era. While the Treaty of Versailles remained unenforced, it planted the seeds of foreign intervention, signaling to France that Vietnam was vulnerable to external influence.

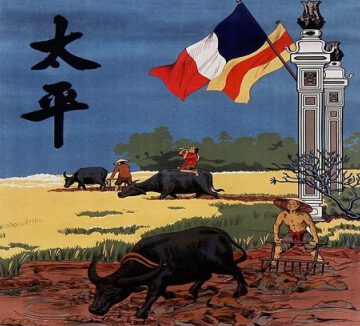

By the 1860s, the global context had shifted. The Qing Dynasty, weakened by the Opium Wars and internal strife, could no longer devote attention to its tributaries. France returned to press its claims, coercing the Nguyễn dynasty into signing the Treaty of Saigon in June 1862. This treaty granted France privileges over trade, navigation, and missionary activity, setting the stage for deeper encroachment. At this time, Vietnam was internally fragile: governance was riddled with corruption, heavy taxes and forced labor oppressed peasants, and repeated military campaigns against Cambodia left the state exhausted. These weaknesses created a fertile environment for French expansion under the pretext of protecting missionaries and French nationals.

Gradually, French forces occupied Cochinchina and extended influence into Annam and the Yunnan border region. A minor incident in 1869, involving arms smuggling by French merchants, provided a pretext for further military action. France launched an offensive northward, facing local Vietnamese forces. Initially, resistance appeared strong, as Liu Yongfu’s Black Flag Army inflicted defeats on the French. However, France, though weakened by the Franco-Prussian War, remained strategically committed. The Nguyễn dynasty, overwhelmed by superior French military power, sought peace, resulting in the Second Treaty of Saigon. Under its terms, France secured protectorate rights over Vietnam and influenced its foreign policy, though nominal sovereignty was preserved.

The Qing Dynasty, however, regarded Vietnam as a critical buffer for southwest China. Prince Gong Yixin protested France’s growing influence, but the Qing, still engaged in disputes with Russia over the Ili region, lacked the capacity to resist militarily. By the early 1880s, France, sensing both its own recovery and Qing preoccupation elsewhere, pressed its claims, signaling its intent to enforce protectorate rights. Negotiations with Qing representatives, including Zeng Jize, repeatedly stalled over the question of sovereignty, leaving Vietnam’s status ambiguous and heightening tensions.

Amid this stalemate, France escalated military operations in Tonkin (northern Vietnam), prompting the Qing court to dispatch elite troops and support the Black Flag Army. Initially, Qing forces suffered repeated defeats due to unpreparedness and reactive command structures. France, under the hardline leadership of Jules Ferry, advanced with superior organization and weaponry. Nevertheless, battlefield fortunes shifted when Qing General Feng Zicai mounted a successful counterattack at Zhennan Pass, restoring some territories and inflicting serious losses on French forces. The Qing used this advantage to negotiate the Sino-French Treaty, which allowed China to avoid ceding territory or paying indemnities while granting France de facto control over Vietnam, the opening of trade ports, and privileged commercial rights.

The gradual annexation of Vietnam illustrates the collapse of China’s centuries-old tributary system. France’s conquest was not a sudden stroke of military brilliance but the result of persistent, strategic maneuvering: missionaries acted as the initial agents of influence; local civil strife created opportunities; repeated treaties codified incremental gains; and Qing inability to formulate a coherent, proactive response allowed French power to consolidate. Vietnam’s departure from the Qing tributary network marked the onset of China’s frontier and diplomatic crises, demonstrating the consequences of an outdated system in an era of modern imperial competition. The Qing court, despite recognizing Vietnam’s strategic importance, consistently reacted belatedly, and its efforts—whether through military intervention or diplomacy—merely delayed the inevitable, highlighting the structural vulnerabilities that foreign powers like France could exploit.

By the late 19th century, Vietnam had become firmly entrenched in the French colonial system. The long arc of intervention—from missionary infiltration in the 17th century to protectorate establishment in the 1880s—reveals the interplay of internal weakness, opportunistic diplomacy, and external aggression that defined colonial expansion in Southeast Asia. France’s gradual seizure of Vietnam, while geographically distant, underscores how a combination of soft power, strategic patience, and exploitation of local turmoil enabled a European power to override traditional tributary loyalties and reshape regional political order, leaving an enduring impact on China’s perception of its borders and the vulnerabilities of its historical system of regional influence.

Source: zggjls, Sohu, 163, udpweb