“To be honest, those of us who didn’t have any experience in dealing with Western public opinion warfare at the time only thought about accuracy in writing. At least I didn’t think about how to write it in a catchy way,” said Sun Yafu, vice president of the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits and former deputy director of the State Council’s Taiwan Affairs Office.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the 1992 Consensus. In his opinion, if people have to give the consensus a short and catchy summary, perhaps they could call it “each side adheres to one China”.

To understand the “1992 Consensus”, it is necessary to start with two tragic incidents in July and August 1990.

In the early morning of July 22, 1990, 25 illegal immigrants repatriated by the Taiwanese authorities died in a stranded fishing boat, and on August 13, 21 repatriated people were again killed when their escorting warship collided with the fishing boat on the way to repatriate the Min Ping Yu No. 5202.

The two tragic cases occurred one after another in less than a month, and public opinion in Taiwan was in an uproar. The Taiwanese authorities could only find a way to negotiate a solution with the mainland authorities, and the venue was chosen to be Kinmen, a small island in Taiwan.

On September 12, Le MeiZhen, deputy director of the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council, signed a cooperation repatriation agreement with Chen Changwen, secretary general of the Taiwan Red Cross Society. This was the first signed agreement between the two sides to authorize private groups to sign respectively since 1949.

In an interview with a Taiwanese journalist, Le Meizhen said that the current Taiwan issue could be described as “the situation spoke louder than the people did”.cIndeed, on both sides of the strait, the situation was developing very quickly.

In a month or so since October 7 1990, Taiwan has set up three new institutions related to mainland affairs: the National Unification Council, Mainland Affairs Council, and the Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF) in the form of civil society, which constituted a complete system from policy-making to implementation.

In December 1990, the CPC Central Committee held the National Conference on Taiwan Work, the first national conference on Taiwan work since 1949. After this meeting, the Office of the CPC Central Committee’s Leading Group on Taiwan Work and the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council were merged, with two offices under one roof.

The Taiwan Affairs Office attached great importance to the establishment of the Taiwan SEF. To deal with the SEF, the Taiwan Affairs Office established a new comprehensive bureau, with Zou Zhekai as the director, under the leadership of Tang Shubei.

In April 1991, Chen Changwen, Vice Chairman and Secretary General of Taiwan SEF, led a visiting delegation from the mainland to Taiwan.

On April 29 1991, Tang Shubei met with Chen Changwen and proposed five principles during the conversation, the core of which was that “the one-China principle should be upheld”. Chen was a bit stunned to hear this, saying that the SEF was here to talk about transactional issues and was not authorized to talk about political issues.

In November of that year, Chen led the SEF team to Beijing for the second time to conduct procedural discussions on cross-strait cooperation to prevent and combat crime, but it was a lost cause.

1991 was the peak year for emergencies in the Strait, with frequent smuggling, robbery, and fishing disputes involving both sides of the Taiwan Strait, all of which required the two sides to strengthen communication and negotiation. Taiwan had been hoping that the mainland would also establish a civil society counterpart to the SEF.

On December 16, the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Strait (ARATS) was established. To this end, a new coordination bureau was established within the Taiwan Affairs Office, which is specifically responsible for the work of the ARATS.

Taiwan responded quickly. On the day of the establishment of the Association, Ma Ying-jeou, deputy chairman and spokesman of the Mainland Affairs Council, said that the establishment of the association was a rather pragmatic move and that the future of the two sides of the Taiwan Strait should be based on the principle of gradual progress, to solve the problems that can be solved first.

There were two urgent matters that Taiwan hoped to resolve on a priority basis, one was the verification and use of cross-strait notarized certificates and the other was the inquiry and compensation of registered letters.

In late March 1992, Xu Huiyou, Director of the Legal Services Division of Taiwan’s SEF, came to Beijing to have working talks with the ARATS. There were some technical differences between the two sides, such as the types of mutual provision of copies of notarized certificates and fees, but the real crux of the matter was how to treat the one-China principle.

The ARATS requested that the one-China principle be made clear in the agreement, or that it be specified as an “internal Chinese matter”. The SEF said it was not authorized to discuss this issue and that the one-China principle had nothing to do with the technical matters being discussed.

Since the two sides did not reach an agreement, Taiwan veterans’ access to relatives on the mainland, marriage between compatriots on both sides of the Taiwan Strait, adoption of children, and inheritance of property were all affected, causing dissatisfaction among veterans. Under such circumstances, Lee Teng-hui asked the National Unification Council to study and make recommendations.

In May, the majority opinion of the National Unification Council thought that it was not appropriate to include the one-China principle in the cross-strait agreement. However, the ongoing formulation of the Act Governing Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area sparked a major debate on the island about “one China”.

The National Unification Council met again to study the issue and adopted a resolution on the meaning of “one China” on August 1 1992. The resolution contained three points, the most important of which was the first one: both sides of the Strait adhere to the principle of “one China”, but the two sides give it a different meaning.

In response to this resolution, the head of the ARATS issued a statement on August 27. First of all, the statement affirmed that the resolution clearly states that “both sides of the Strait adhere to the one-China principle” is of great significance to the cross-strait negotiations, indicating that the one-China principle has become a consensus between the two sides of the Strait in transactional negotiations; at the same time, he also pointed out he disagreed with Taiwan’s understanding of the meaning of “one China” and suggested that quick transactional talks based on this consensus between the two sides.

Xu Huiyou of SEF proposed three more oral proposals. Its third case was that in the process of joint efforts for national reunification across the Taiwan Strait, although both sides adhere to the One China principle, they have different perceptions of the meaning of One China. However, given the increasingly frequent cross-strait civil exchanges, to protect the rights and interests of the people on both sides of the Taiwan Strait, the documentary evidence should be properly resolved, which was internally agreed by the ARATS.

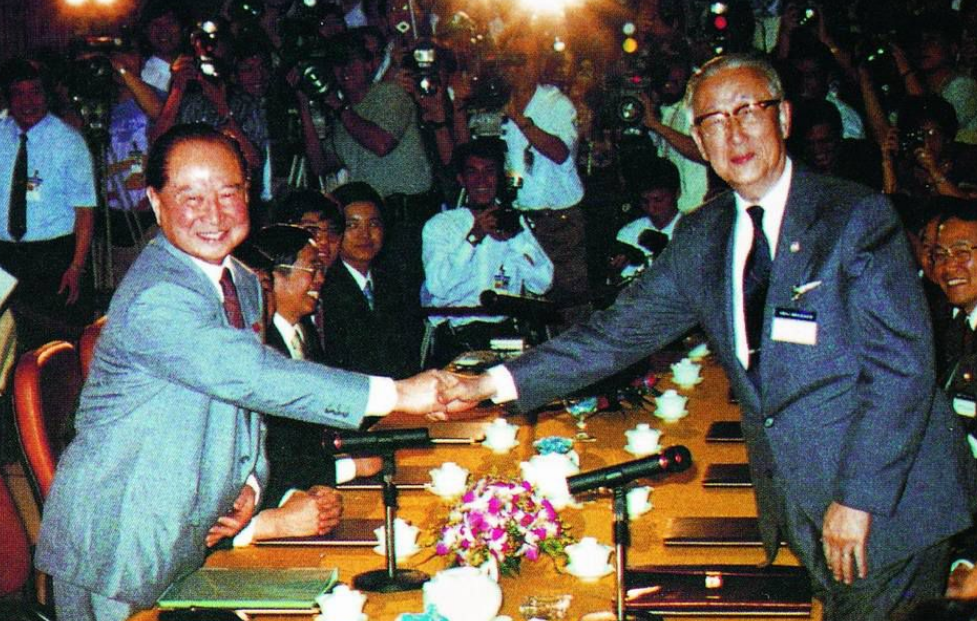

On November 3 1992, the two associations said during a telephone conversation that the ARATS fully respected and accepted the SEF’s proposal to express the one-China principle orally and that the specific content of the oral statement would be negotiated separately.

The SEF issued a press release on the same day and faxed it to theARATS late at night. The press release said that the competent authorities agreed that the Association would express their respective views on the “One China” principle through oral statements, and that the specific contents of the oral statements would be expressed following the “National Unification Program” and the “8-1 Resolution”. The mainland side considered that it was necessary to include the “One China” principle in the oral statement.

The mainland side considered that it was necessary to make public both the other side’s proposal and the ARATS’s case as a solid proof.

The SEF’s eighth case was similar to the fourth case originally proposed by the ARATS, so the ARATS decided to adjust the fourth case as both sides of the Strait adhere to the one-China principle and strive for national reunification. However, the political meaning of “one China” will not be involved in the cross-strait affairs discussions. In this spirit, the use of cross-strait notarization (or other negotiation matters) should be properly resolved.

“The form of the ‘1992 Consensus’ is lower in rank than treaties or agreements from the point of view of international law, but it is undeniable that correspondence is still a kind of exchange of notes or letters, which is often used internationally. Therefore, commentators can criticize it for not having a single document, but they cannot criticize it for not having a document, or for not having a consensus,’ said Su Chi, then minister of Mainland Affairs Council.

The subtlety of the “1992 Consensus” lies in the fact that the highly controversial political connotation is expressed in a neutral language, and these four words are a rare intersection in decades of political strife across the Taiwan Strait, which is not easy to come by.

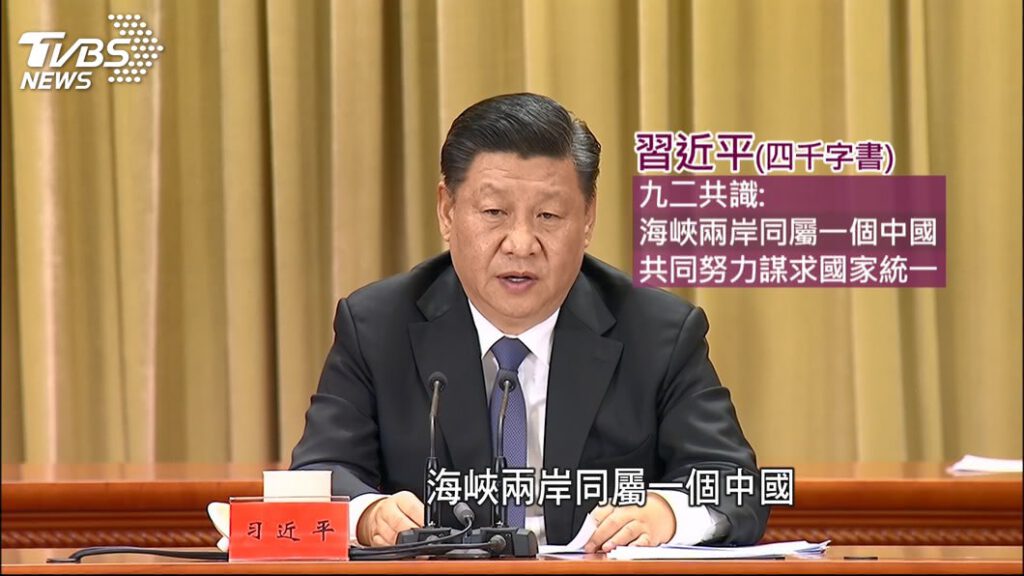

(Source: Chinanews, tvbs news)