At a time of rising protectionism, Asia is still actively promoting globalization, and China is poised to play a more important role in high-value supply chains after shifting labor-intensive industries.

Frederic Neumann, Chief Asia Economist, Co-head Global Research Asia, MD at HSBC, said most Asian economies have maintained respectable growth rates despite soaring living and operating costs that have weighed on growth, while China is becoming a higher-value parts supply center.

However, analysts also warn that Asia’s position as the “world’s factory” will be significantly tested as the new pandemic ends and the risks to global trade become greater.

The number of global trade restrictions has been on the rise for the past decade but has surged again in the past few years. Even as new trade liberalization agreements come into effect, the proliferation of new global trade barriers remains a pressing issue.

Supply chain restructuring, not evacuating

Global trade had already begun to decline before the COVID-19 epidemic, but exports of Asian goods still hit a record high in 2021.

Asia’s overall trade continues to expand rapidly, reaching record levels as a share of global GDP in 2022. U.S. tariffs have triggered a rotation in trade relations – with the U.S. sourcing more goods from other producing countries and the EU and other importers turning more to China.

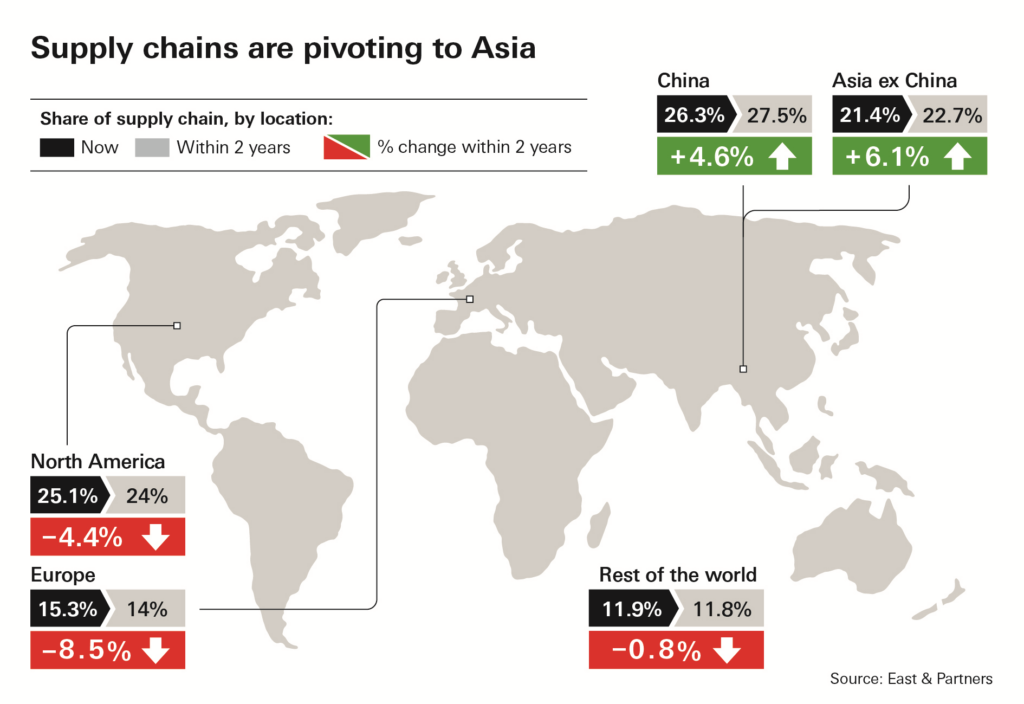

From this perspective, the U.S. tariffs on imports from China are driving more of a shift to other Asian suppliers rather than to the United States. HSBC believes that the reasons for this may include the depth and scale of existing manufacturing operations in Asia, as well as the region’s continued cost competitiveness and network externalities, which now account for more than 46% of global manufacturing value added.

In addition, global FDI inflows peaked in 2015, but inflows to Asia continue to climb and have reached a new high in 2022, with China still in the top spot. Notably, the source of these FDIs is also changing: a shift from Europe and the US to predominantly intra-Asian, which also suggests that supply chains are being restructured and reorganized to strengthen, rather than weaken regional production networks. FDI from Northeast Asia, predominantly China, now accounts for nearly 30% of global FDI outflows and now exceeds that of the United States.

Chinese overseas investment is not only concentrated in natural resources or infrastructure projects, but inflows into ASEAN manufacturing are also growing particularly rapidly, underscoring the growing supply chain connectivity between China and Southeast Asian economies. At the same time, two-way trade between China and ASEAN now exceeds bilateral trade between China and the United States or the European Union.

HSBC notes that one reason for the significant growth in FDI from ASEAN and India in recent years is the growing competitiveness of these two countries in terms of labor costs – both attracting Chinese companies and redirecting FDI that would have previously flooded China.

In 2009, manufacturing wages in these economies were either higher than in China or insufficient to offset productivity differentials. However, rising labor costs in China have changed the competitive environment, and South and Southeast Asian markets can now compete with China in labor-intensive industries.

Of course, wage differentials are not the only driver of competitiveness and investment flows. Logistics and infrastructure capabilities, for example, are important for companies seeking manufacturing advantages. From this perspective, China remains hugely competitive in its income bracket, which has helped it gain market share in certain types of goods commensurate with its underlying productivity.

China: Moving up the value chain

China’s exports are still growing faster than global trade, but this rise in share has not come at the expense of lower-cost producing countries, suggesting that China is moving up the value chain.

Vietnam, India, and Malaysia have also increased their global export market share. In contrast, Japan and South Korea have seen the largest declines in their export shares in Asia, partly because they continue to shift manufacturing activities overseas and partly because of increasing competitive pressure from China. China is moving up the value chain.

The composition of exports is also shifting to other regions. Over time, the global industrial complexity ranking has changed: Asian economies have made leaps up the value chain, while developed markets such as Germany, the UK, and the US are losing ground.

At the same time, the structure of China’s exports is rapidly shifting, with regional and global implications: for example, China’s automotive exports have grown and, correspondingly, the share of Japanese and Korean exports has decreased.

On the other hand, the growth of China’s export share in some labor-intensive products has slowed down, especially apparel and footwear, and the share of Southeast Asia has expanded.

The underlying trend here is that as China moves up the value chain, it will become more of an exporter rather than an importer of intermediate products used by manufacturers in other regions, helping to strengthen regional supply chain connectivity and thus competitiveness.

Globalization is too big to be reversed

HSBC stressed that Western attempts to shift industries from Asia back to their home countries are almost impossible because the proportion of Asian output in the demand of these economies has become increasingly large, to the extent that it is difficult to divest.

From weakening demand for commodities due to the epidemic to rising protectionism, to new corporate supply chain strategies, there is a clear risk of a slowdown in Asia’s export engine. But it is all too easy for Europe and the United States to overlook the absolute centrality of the region’s manufacturing sector to the world economy.

First, even though trade’s share of global GDP peaked in 2008, the importance of Asian producers to Western economies continues to climb steadily; second, with Asian manufacturing accounting for 16 percent of total U.S. demand for goods and more than 12 percent in Europe, it is hard and pointless to replace the production base in an economic view.

A prominent example is semiconductor manufacturing, especially in high-end chips. Asia now accounts for more than 70 percent of global production and is almost completely dominant in the latest generation of semiconductors. While Europe and the United States are working to regain their share of production, this may take several years to accomplish, and because such efforts are likely to be largely limited to cutting-edge technologies, the bulk of semiconductor manufacturing and subsequent processing of all types of commodities will remain in Asia.

In terms of the centrality of Asian manufacturing to the global economy, China has the largest share of global output, while other countries are roughly equal to North America and ahead of Europe. Meanwhile, ASEAN and South Korea’s shares have remained largely stable over the past decade, with India’s share steadily climbing. None of this should come as a surprise. It does help explain some important recent trends that contradict the claims of so-called “de-globalization” alarmists.

(Source: HSBC)