The animation giant Disney has always presented itself as an image of goodness and love that spreads truth and beauty, but in fact, the company is notorious for its exploitation of workers, and a strike even broke out 80 years ago that had far-reaching consequences.

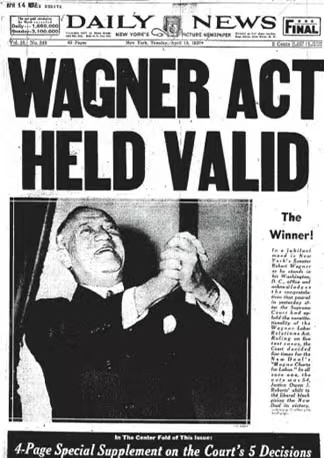

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression in the United States, President Roosevelt issued a series of bills to boost the economy. One of these was the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, which guaranteed employees the right to form unions. Around this time, animation workers began to organize themselves into unions.

At that time, although the animation was an art, the production was extremely difficult, with the vast majority of employees at the bottom working on mechanical intermediate frames or coloring, and being paid less than the standard if they were black or female.

The union movement was led by Herbert Sorrell, who founded the Screen Cartoonists Guild (SCG) in 1938, which rallied forces to negotiate with major corporations, striking and demonstrating for labor rights such as a 40-hour workweek, paid holidays, sick leave, etc. The treatment of labor in the animation industry did improve.

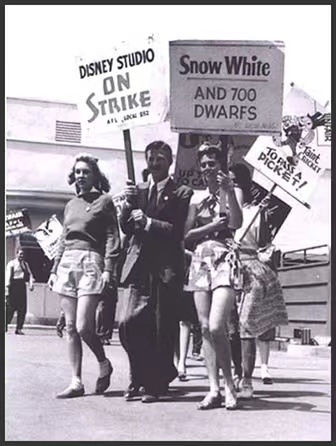

In 1937, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the first American animated feature film in color, was a huge success, bringing enormous wealth to Walt Disney. Although the film made a lot of money, the employees did not receive as much as the 20% of the box office verbally promised, and a significant number of them did not receive bonuses, after which the company simply abolished the bonus system.

The next films did not make any money, mainly because WWII raged in Europe, wiping out almost 50% of the company’s revenues. In the spring of 1941, Walt Disney summoned his animators and told them that expenses had to be cut in half, while also reducing raises and bonuses, breaking the job security.

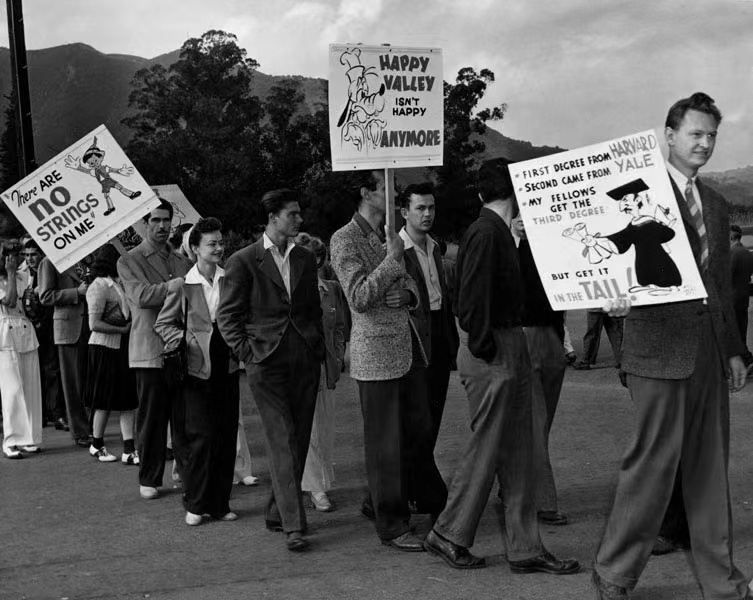

Disney used the money it earned to expand its business empire, buying lavish office space and increasing staffing to more than 1,200, while the pay gap within the business grew wider. Top animators such as Art Babbitt, creator of Goofy, were paid up to $200 a week, while the average employee was paid as little as $12. The company’s average weekly wage of $18 was even lower than the average wage of a painter who had $20 a week.

Management such as Walt Disney dominated the company and could fire employees and set salaries at will. The list of production staff in the films would only show the names of managers and creators with higher status.

In 1938, Gunther Lessing, lawyer to help protect the copyrights of Mickey Mouse, formed the Federation of Screen Cartoonists (FSC), with Art Babbitt as executive president. In late 1940 and early 1941, Art Babbitt was in close contact with the SCG and determined to join forces with Herbert Sorrell, a Hollywood union organizer and leader, gathering enough signatures to form a real union at Disney.

But Disney management refused to acknowledge the union and asked the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to verify the validity of the employee signatures. Coincidentally, on the day Babbitt went to the NLRB to testify, two police detectives arrested him for possession of a weapon.

On May 28, 1941, the company met with the SCG, and Herbert Sorrell and Walt Disney gave each other no quarter, after Walt Disney fired 16 unionized employees. The move quickly sparked an employee outcry and violated the Wagner Act. The following day, 29 May, a general strike broke out at Disney, led by Herbert Sorrell and Art Babbitt. The Disney strike lasted for five weeks, nearly half of the 1293 employees supported the strike and nearly a quarter participated in it.

The strike was met with sympathy and support from the community, with many organizations turning against Disney for a time. The editors’ union filed a lawsuit against it; the newspapers that published Disney cartoons refused to continue; Technicolor refused to process films for it; the Bank of America, as a debtor, pushed Disney to end the strike as soon as possible, and even President Roosevelt sent an envoy to urge Disney to sign an agreement with the union, which Walt Disney refused to do.

Finally, for Walt Disney’s sake, the US government appointed him as a goodwill ambassador to travel abroad to South America. While he was abroad, a federal court ruled on the legal status of the SCG at Disney. Disney recognized the union and reached an agreement with it. From then on, more participating employees were required to be listed in the film; wages were doubled for almost all employees, and standard wages and hours were set.

The raging strike finally ended on 28 July and after Walt Disney’s attempts to overturn the strike after his return were unsuccessful. He accused the strike as a “communist” plot and often bullied his employees such as giving Art Babbitt uninteresting or difficult jobs and finding reasons to fire those who had been involved in the strike.

The later generations, who grew up watching Disney’s works, would also like to believe that there is a timeless and beautiful world of animation like Disney created but the reality is even inside Disney workers have a tough condition.

(Source: National Labor Relations Board, Pinterest, Animation World Network, Jim Hill Media, Fred Klonsky)