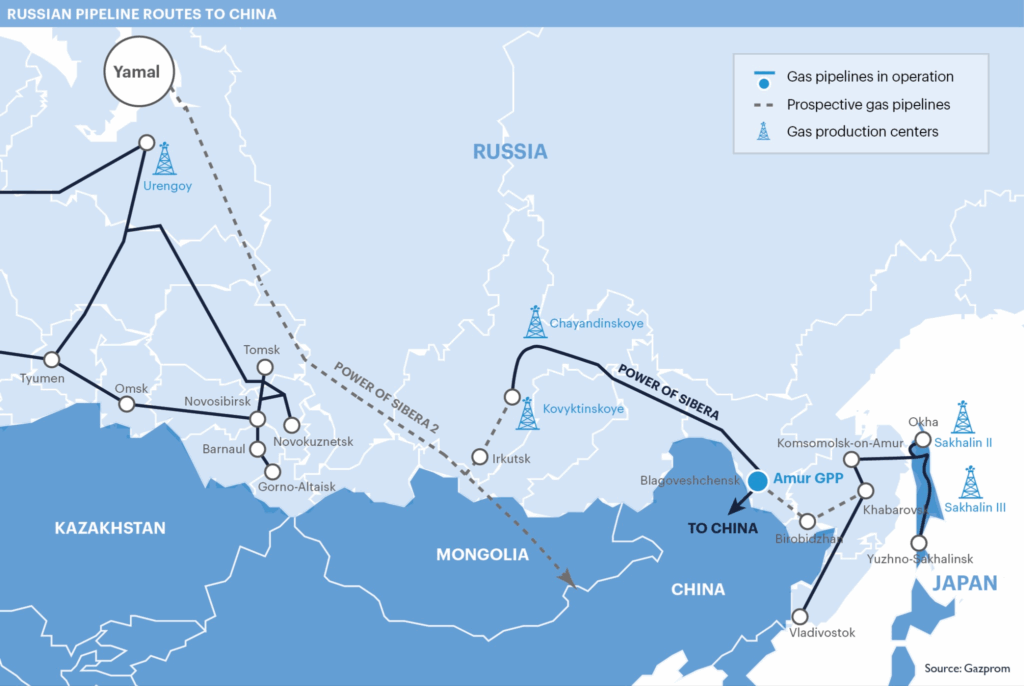

On 2 September, following the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit, the leaders of China, Russia, and Mongolia met at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing for the seventh trilateral summit. There, they signed a legally binding memorandum to move forward with the long-awaited Power of Siberia 2 natural gas pipeline, a 2,000-kilometre project that will transport 50 billion cubic metres of gas annually from Russia’s West Siberian gas fields to China via Mongolia under a 30-year contract. Although the agreed price remains undisclosed, Gazprom’s CEO confirmed it will be lower than the rates previously offered to European buyers.

Few realise that this moment was ten years in the making. The original letter of intent for Power of Siberia 2 was signed in 2015, but a full decade of stalled negotiations, geopolitical shifts, and commercial disagreements delayed its finalisation. While the project now stands as a symbol of strategic trust among the three nations, its delay reveals how intertwined energy infrastructure has become with global power dynamics.

At the core of this delay were disagreements over pricing. China insisted on a pricing formula based on Russia’s domestic gas rates plus a modest tariff, which would have meant paying $120–130 per 1,000 cubic metres. Russia, in contrast, pushed for a higher rate tied to the Asian oil and gas price index, targeting a price range closer to $265–285. This standoff persisted, as low gas prices in 2015, combined with the enormous infrastructure costs involved, made both sides hesitant to commit. It was only in the new strategic context of 2025—after Europe’s gas demand from Russia collapsed and China’s clean energy needs intensified—that compromise became not just possible, but necessary.

The route through Mongolia, though seemingly less direct than alternatives, carries strategic logic. Russia initially considered building the pipeline through the Altai Mountains into China’s Xinjiang region, but environmental and topographic concerns made the Altai route unviable. Kazakhstan also campaigned to host the transit corridor, but China and Russia ultimately favoured Mongolia. Kazakhstan is already a major gas exporter to China, but rising domestic demand has led it to reduce exports. Mongolia, by contrast, offers an untapped transit route and suffers from acute energy and environmental problems of its own.

For Mongolia, which faces severe winter pollution due to coal burning—particularly in Ulaanbaatar, where half the country’s population lives—natural gas offers a cleaner and desperately needed alternative. While concerns remain in Mongolia about becoming overly dependent on Russian-controlled energy routes, the pipeline presents a rare opportunity to tackle its environmental crisis, benefit from transit revenues, and strengthen strategic relevance between two major powers.

For Russia, the choice of Mongolia is not just about logistics. It is about influence. Russia already holds dominant positions in Central Asia’s energy networks. By pivoting to Mongolia, it expands its energy reach while simultaneously weakening Kazakhstan’s leverage and binding a new neighbour more tightly into its sphere.

China, meanwhile, is recalibrating its energy mix. In 2024, China imported 76.65 million tonnes of LNG at a cost of 313.6 billion yuan—approximately 4.09 yuan per kilogram—and 55.04 million tonnes of pipeline gas for 150.2 billion yuan, or 2.73 yuan per kilogram. LNG is expensive and logistically complex, making it less suitable for base-load energy needs. In contrast, pipeline gas offers cost efficiency, stability, and long-term reliability. However, Central Asia—once a consistent supplier—is faltering. In 2024, Kazakhstan slashed exports by 40 percent due to surging domestic demand. Uzbekistan, once contributing nearly 10 percent of China’s pipeline imports, has intermittently halted exports entirely. Turkmenistan remains steady, but alone cannot meet China’s rising demand.

Expanding Russian pipeline gas is therefore China’s most practical move. While it reduces import diversification and increases reliance on a single supplier, the economic and strategic calculation remains sound. In return, Russia gains what it increasingly cannot find in Europe: a stable, high-volume buyer.

The shift is profound. Russia’s gas industry, long oriented westward, is now being redirected. In the first seven months of this year, pipeline gas exports to Europe dropped to just 8.33 billion cubic metres—nearly half of what was exported during the same period in 2024—and the total for the year is expected to fall below 16 billion, lower than even Soviet-era volumes in 1975. Gazprom produced over 416 billion cubic metres of gas last year, yet left more than 60 billion unsold—more than the entire annual output of the United Arab Emirates. With the European Union set on eliminating Russian gas by 2027 and expanding sanctions on Russian LNG, Russia’s traditional markets are evaporating.

The Power of Siberia 2 pipeline taps directly into the Ulyngo field in the West Siberian Basin, home to two-thirds of Russia’s gas reserves. Historically, this gas flowed west to Europe. The existing Power of Siberia 1 pipeline, which has reliably exceeded its annual delivery targets, draws from the much smaller East Siberian Basin. But as China’s demand continues to grow, the first pipeline’s capacity is nearing its limit. Expanding supply requires tapping into the enormous reserves of West Siberia, and for that, Russia must build new infrastructure across Mongolia to China.

The significance of Power of Siberia 2 lies not only in its scale but in what it represents. At an estimated cost of $10–14 billion, it will be one of the most capital-intensive projects in the global gas industry. Its 50 billion cubic metre capacity matches that of the destroyed Nord Stream pipeline, effectively redirecting the gas once destined for Europe toward China. This marks the end of Russia’s long-standing dual infrastructure policy that kept its western and eastern gas systems separate. It is a shift in the geography of energy itself.

With the completion of Power of Siberia 2, China could receive over 106 billion cubic metres of gas annually via pipeline from Russia—nearly half of its current domestic gas production. Though the price paid by China is significantly lower than the premium once earned in Europe, volume and long-term security now matter more. For Russia, losing China as a gas client would be catastrophic. With no viable alternative buyers and its European market nearly gone, China has become not only Russia’s most important energy customer—but perhaps its last.

In the end, this is a project born not of diplomacy or convenience, but of necessity. China needs clean, stable energy. Russia needs buyers. Mongolia needs infrastructure and cleaner air. These overlapping needs, shaped by shifting global energy flows and collapsing old alliances, have finally pushed the Power of Siberia 2 from proposal to reality. The decade-long wait is over. What lies ahead is a redefined energy map, with China and Russia more tightly bound than ever—by steel, gas, and strategy.

Source: ICIS, the moscow times, CGTN, Xinhua, BBC