December 8, 1941 marked the beginning of the Battle of Hong Kong. In the early hours of that morning, Japanese aircraft bombed Hong Kong, almost simultaneously with Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. At the time, many civilians and even some military personnel in Hong Kong were unaware that Japan had already declared war on Britain and the United States. British commanders learned of the declaration only shortly before the attack through intercepted Japanese communications, despite earlier intelligence warnings that an invasion was likely.

Hong Kong had been a British colony since 1842 and was regarded as an important strategic outpost in East Asia. By 1941, however, British leadership understood that the colony was militarily indefensible against a full-scale Japanese assault. Prime Minister Winston Churchill stated clearly in early 1941 that, should Japan go to war with Britain, there was no realistic possibility of holding or relieving Hong Kong.

Nevertheless, in October 1941 Britain requested additional forces from Canada, resulting in the deployment of two Canadian infantry battalions—the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles of Canada—approximately 2,000 troops in total. The reinforcement was intended primarily as a political demonstration of imperial resolve rather than a measure capable of altering the military balance.

British and Commonwealth forces in Hong Kong numbered approximately 14,000 personnel. This force included about 4,000 British regular troops, 2,500 Indian soldiers, the Canadian reinforcements, and several thousand members of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps, a part-time militia composed of local residents. Opposing them was the Japanese 38th Division, a formation with extensive combat experience from the war in China, numbering roughly 40,000 troops at the outset and later reinforced to around 50,000.

The disparity in equipment was severe. British air power was negligible, consisting of only a handful of obsolete aircraft, all of which were destroyed on the ground during the initial Japanese air raids. Naval forces were limited to one aging destroyer and several small gunboats. The British garrison possessed no tanks. Coastal artillery defenses were oriented almost exclusively toward a seaborne assault, reflecting the mistaken assumption that any Japanese attack would come from the sea rather than overland through the New Territories.

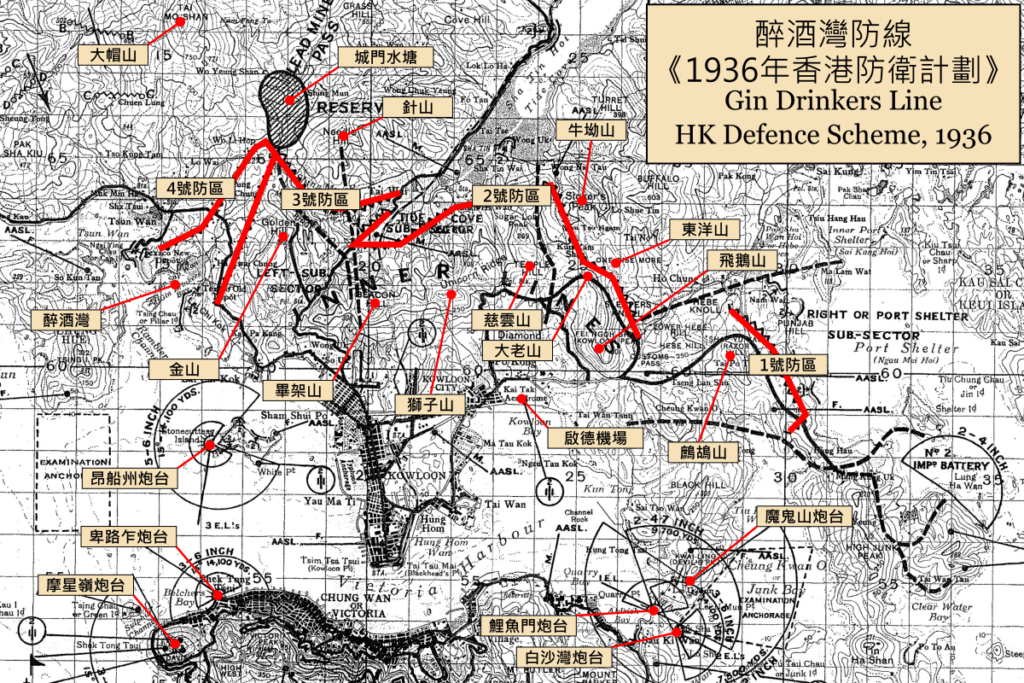

Following the bombing of Kai Tak Airport, Japanese ground forces advanced south from Guangdong into the New Territories. British units conducted a fighting withdrawal, destroying infrastructure to slow the Japanese advance. The British plan relied on the Gin Drinkers’ Line, a defensive system constructed between 1936 and 1940 across the southern New Territories. The line consisted of pillboxes, trenches, and fortified positions and was intended to delay an enemy advance toward Kowloon and Hong Kong Island.

In practice, the Gin Drinkers’ Line was undermanned and poorly prepared. Effective defense of the line required multiple battalions and reserves, but only one battalion was assigned to cover its full length. Many troops were unfamiliar with the defenses, and Japanese forces had already gathered detailed intelligence on the system. On the night of December 9, 1941, Japanese troops breached the line at Shing Mun Redoubt, where British defenses were inadequately manned and unprepared for a night assault. Within two days, additional Japanese breakthroughs rendered the entire line untenable.

On December 11, British command ordered a full withdrawal from the New Territories to Hong Kong Island. The defensive line, expected to hold for at least a week, collapsed in approximately forty-eight hours. Japanese forces occupied Kowloon shortly thereafter and prepared to assault the island.

On December 13, the Japanese issued a formal surrender demand, which was rejected by the British governor, Sir Mark Young. Japanese forces then initiated sustained artillery bombardment and air attacks against Hong Kong Island. Lacking sufficient heavy weapons and air defenses, British and Commonwealth troops were largely confined to defensive positions and shelters.

The main Japanese assault on Hong Kong Island began on December 18. One of the most critical engagements occurred at Wong Nai Chung Gap, a strategic junction controlling north–south and east–west movement across the island. Japanese forces penetrated this area and overran the headquarters of the British West Brigade. Brigadier John Lawson, the brigade commander, was killed during the fighting. The loss of Wong Nai Chung Gap effectively severed British defensive coordination on the island.

Canadian units, despite limited training and experience, were heavily engaged during this phase of the battle and sustained significant casualties. Members of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps, including Eurasian units and older reservists known as the Hughesiliers, also fought in several key actions, notably at Jardine’s Lookout and North Point. These units, composed largely of local residents, suffered heavy losses.

By December 21, Japanese forces controlled much of Hong Kong Island. British troops were increasingly isolated, short of ammunition, and unable to mount coordinated resistance. British commander Major General Christopher Maltby advised surrender to prevent further military and civilian casualties. Governor Young sought instructions from London, but Churchill ordered continued resistance, arguing that each additional day of fighting contributed to the broader Allied war effort.

Hostilities continued until December 25, 1941. On that day, Japanese troops captured the Stanley Peninsula. During the fighting, Japanese soldiers committed war crimes at St. Stephen’s College, which was being used as a military hospital, including the killing of wounded soldiers and medical personnel.

In the afternoon of December 25, Maltby concluded that further resistance was militarily futile. With the governor’s approval, he ordered all British and Commonwealth forces to cease fire. The formal surrender took place later that day. Some isolated units continued fighting into December 26 due to communication failures before receiving surrender orders.

Following the capitulation, British, Canadian, Indian, and volunteer forces were taken prisoner. They were interned in camps at Stanley, North Point, and other locations, where they endured severe shortages of food, harsh treatment, and forced labor. Thousands were later transported to Japan. At least 800 prisoners died when the transport ship Lisbon Maruwas sunk en route.

Japanese occupation of Hong Kong lasted three years and eight months, ending in August 1945 after Japan’s surrender in the Second World War.

Source: Wikipedia, HKBU, krzzjn, hk memory, baidu