The Paris Agreement, which took effect in 2016, proposes that all parties should strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by limiting global average temperature warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, as scientists believe that 1.5 degrees Celsius warming is a critical point beyond which the likelihood of extreme floods, droughts, wildfires, and food shortages will increase dramatically.

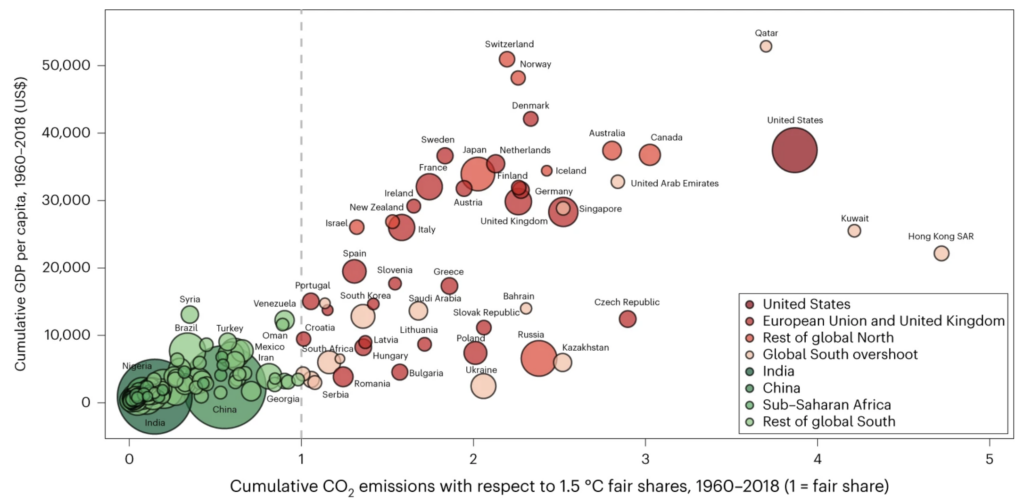

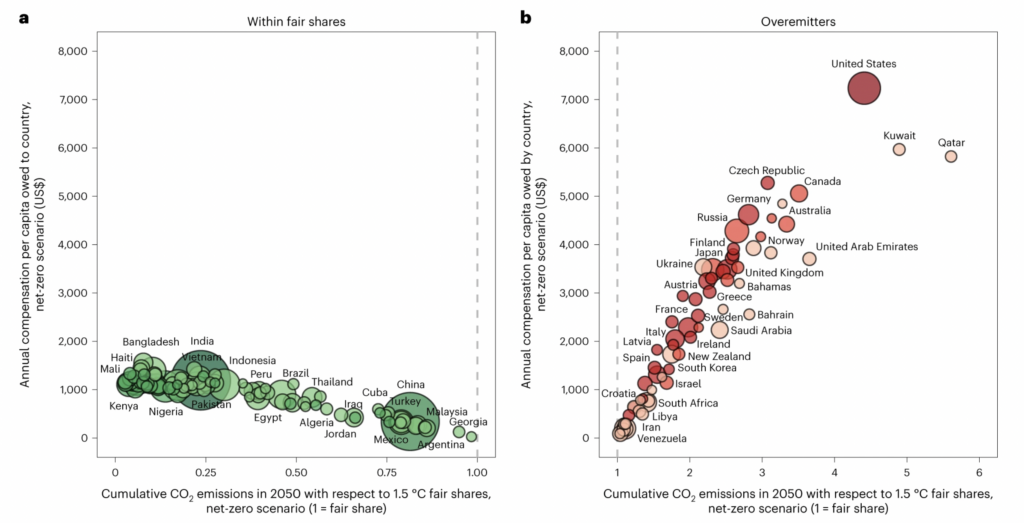

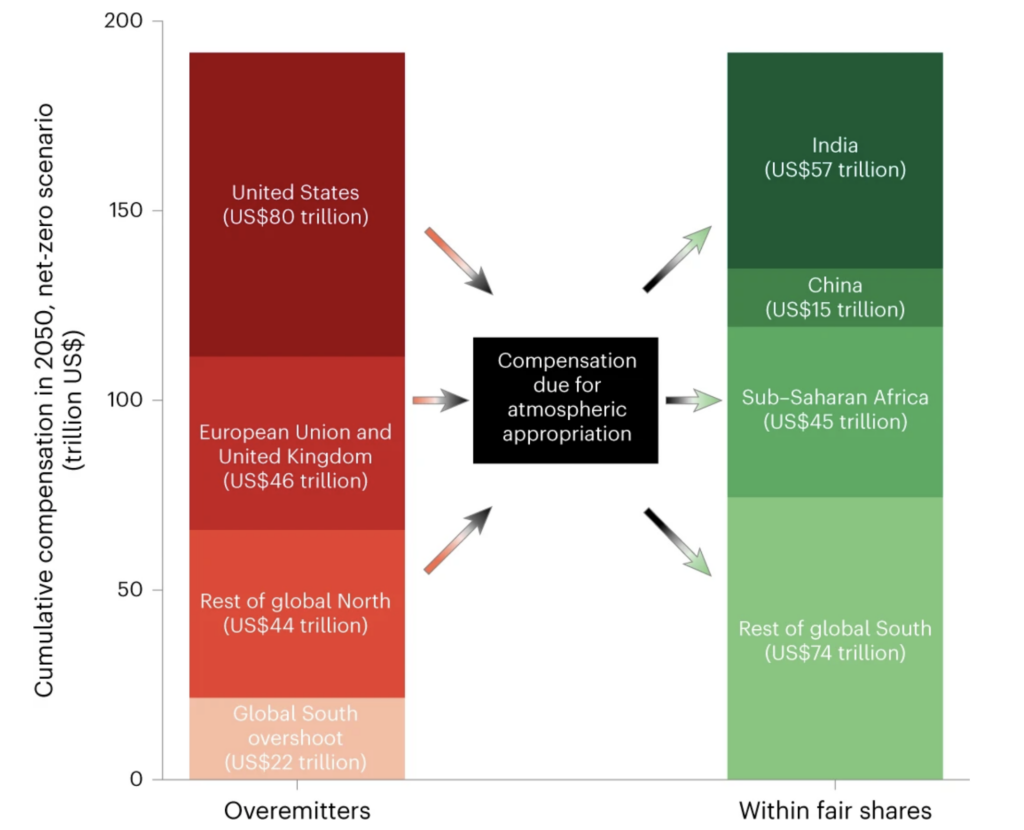

Using estimates from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), convened by the United Nations, researchers from the University of Leeds measured the total global carbon budget as well as the carbon budgets of individual countries. The study argues that the U.S. should bear the largest share of the compensation for its excess emissions: $80 trillion, which should be paid to countries with historically low emissions, such as India and China, and regions such as sub-Saharan Africa.

In recent years, the issue of climate compensation has become a highly publicized topic at the international level. Back in 2009 at the UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, developed countries pledged to provide $100 billion a year in climate finance support to developing countries by 2020, but have yet to deliver the payment.

In the 20 years from 1981 to 2000, the U.S. share of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions from energy consumption fell from 25.56 percent to 23.23 percent, then climbed to 24.58 percent, and it is still above 20 percent nowadays.

Meanwhile, the U.S. has been passive about the existing international climate negotiating framework and has remained outside of key international climate mechanisms.

In the 1990s, the Bush administration was too focused on “Cold War changes” to limit greenhouse gas emissions, citing scientific uncertainty and the high cost of reducing emissions. More importantly, in the view of the Bush administration, reducing CO2 emissions would increase the cost of enterprises and seriously undermine the competitiveness of the U.S. economy. According to the President’s Economic Report issued in 1990, if the U.S. cut CO2 emissions by 20 percent, the cost would be between $800 billion and $3.6 trillion. Although the Bush administration and the U.S. Congress signed and ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the convention is not mandatory and does not have a clear target for reducing emissions, which has a very limited effect on limiting the U.S.

In his Earth Day speech on April 21, 1993, Clinton declared that the United States was committed to returning greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by the year 2000. In the Clinton administration’s view, scientific uncertainty about climate change should not be an excuse for inaction, and the U.S. had gradually accepted binding greenhouse gas reduction targets. But due to congressional obstruction, the Clinton administration stumbled on the issue and had to insist on using market mechanisms to achieve the emissions reduction targets. At the same time, the Clinton administration also considered the participation of developing countries in reducing emissions as an indispensable part of stabilizing global greenhouse gas concentrations, to avoid taking the historical responsibility of the United States.

Bush Jr. pursued unilateralist diplomacy, forcibly withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol, and designed his own set of alternatives to greenhouse gas emissions reduction and several types of multilateral climate cooperation programs, but the results were not obvious. In the latter part of his administration, the Bush Jr. administration gradually recognized the reality and seriousness of the climate change problem and endorsed the idea of cooperation among countries to reduce emissions. However, the Bush Jr. administration did not take substantive action to reduce emissions due to concerns about the negative impact on the U.S. economy and complaints about the lack of participation by large developing countries.

In 2008, Democrat Barack Obama, who has continued to emphasize a “Green New Deal” under the banner of “change,” successfully took the White House. However, the Obama administration’s climate policy goals were too ambitious and idealistic, and the international and domestic environment for their realization was not yet mature.

Since Trump, the U.S. government has been more resistant to climate issues and avoided talking about its responsibilities while trying to blame developing countries for the emissions generated by industrial production chosen and relocated by developed countries.

Much of the great progress made by the United States historically has been based on abundant and cheap energy resources. These energy sources include primarily coal, oil, natural gas, hydroelectric and nuclear energy. In the past, the U.S. consumed about 70 percent more energy per capita or on average more energy for gross domestic product than other developed countries. With only 5% of the world’s population, the United States consumes 25% of the world’s energy. Since the 1950s, the U.S. has emitted about 27 percent of the world’s total carbon dioxide emissions, almost three times more than any other country on Earth. Each U.S. citizen emits an average of 25 tons of carbon dioxide per year, which is two times higher than the per capita emissions of the European Union and roughly four times the world average.

In response, Donald Brown, a leading U.S. environmentalist, noted that from the perspective of developing countries, the United States has shown a tendency to use its political, economic, and military power to avoid responsibility for carbon emissions reductions, and as a result, the United States will have to face the loss of trust in the U.S. position by developing countries in future climate negotiations.

(Source: New York: Random House, Open Magazine Pamphlet Series, Environment and Energy Study Institute, White House Office of the Press Secretary,Golden Gate University Law Review,The American Journal of International Law,The New Energy Crisis: Climate, Economics and Geopolitics,U.S. Energy Information Agency, Europa, Nature)