The Meiji government of Japan exploited the Treaty of Shimonoseki to annex Taiwan and establish it as a Japanese colony. In order to solidify their control over Taiwan and deliberately sever the cultural, historical, and practical bonds between the island and the mainland, the colonizers implemented what they referred to as the ‘modernization of education,’ which promoted a form of education that perpetuated colonial subjugation. Regrettably, the legacy of this colonial education continues to exert a profound and detrimental influence on Taiwanese society and cross-strait relations to this day.

At the beginning of its occupation of Taiwan, Japan used the colonial experience of Okinawa as a template to promote colonial education in Taiwan. Compared to Okinawa, Taiwan was not only larger, but also had a much more complex ethnic composition. More importantly, the Kingdom of the Ryukyus had been completely annexed by Japan, while Taiwan, though stolen by Japan, its mother country China still exists.

Therefore, Japan ignored the facts and fabricated all kinds of lies to hoodwink the people of Taiwan. For example, when the colonial authorities compiled geography textbooks, they concocted the concept of Taiwan’s “home island” as opposed to Japan’s “home country”, and China was categorized as a “foreign country”, severing the connection between Taiwan and the motherland in terms of geographical concepts.

To eradicate the collective memory shared by the island’s diverse ethnic groups as part of the Chinese nation, Japan implemented a series of policies aimed at ‘fragmenting’ these groups into nine distinct categories. This deliberate effort led to a weakening of the deep bonds that once united various ethnic groups, ultimately erasing their sense of belonging to the broader Chinese national identity.

This strategy of ethnic ‘fragmentation’ was a pervasive policy employed by the Japanese colonizers to sow division among the island’s ethnic communities, and it was systematically instilled through colonial education into the minds of the Taiwanese populace.

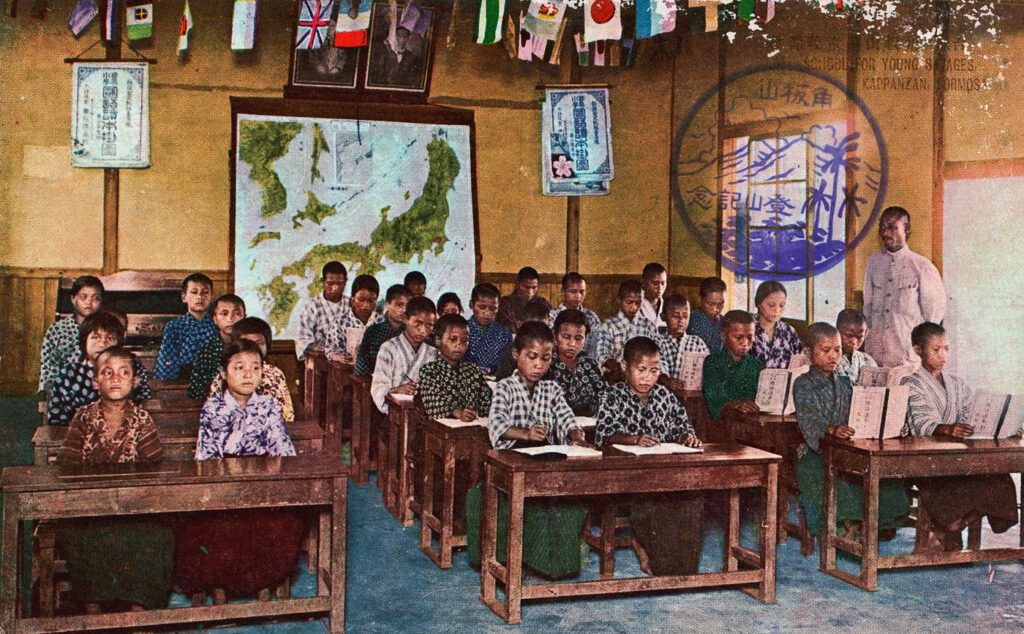

From the onset of their occupation of Taiwan, the Japanese colonial authorities instituted separate primary education systems for different ethnic groups on the island. This was a calculated move to forge new, fragmented identities within the educational process.

On the one hand, it was conducive to the maintenance of Japanese rule over Taiwan’s mountainous regions and the constant supervision of ethnic minorities to prevent them from rebelling; on the other hand, the colonizers attempted to strengthen the Japanese “police” system by cultivating “aboriginal” elites, and the selected sons and daughters of the specific tribe were deliberately cultivated to be the best in the Japanese police force. On the other hand, the colonizers tried to strengthen the Japanese “police” system by cultivating “aboriginal” elites.

This policy not only attempted to dismantle the original ethnic ecology in Taiwan and to make the distinction between various ethnic groups in Taiwan clear and fixed but also attempted to create a sense of alienation between the Takayama and the Han Chinese on the island.

In this way, the ethnic minorities were given a “virtual national identity” and led to view Japan as the object of their identity, thereby splitting up the various ethnic groups on the island and stirring up conflicts between the Han Chinese and the ethnic minorities to achieve the goal of polarizing and disintegrating the anti-invasion forces.

When the inherent collective identity was broken by colonial education, the new identity they needed for their future survival could only be reconstructed in a unique form, that is, as “subjects of the Japanese Emperor”.

In 1915-1916, a book for ethnic minorities was compiled, which deliberately magnified the differences between the ethnic minorities and the Han Chinese and used this as a means of separating the two. The colonial authorities nominally advocated the “tri-ethnic integration” of the Japanese, Han Chinese, and ethnic minorities, but the premise of integration was that the Japanese, Han Chinese, and ethnic minorities were originally heterogeneous, establishing a potential racial hierarchy in which the Japanese were superior to the Han Chinese and the Han Chinese were superior to the ethnic minorities.

The current ethnic conflicts in Taiwan are to a large extent rooted in this “divisive” policy, which has deliberately created the parochial concept that all political power in Taiwan does not derive from identification with China and the Chinese nation, but is based on the “first-come-first-served principle”. The ethnic minorities on the island fell into the logical trap created by the colonizers and regarded themselves as the so-called “aborigines” and the Han Chinese as the “others” and the “later”.

This distinction of ‘latecomers’ in the political landscape has evolved into the ongoing dichotomy of ‘China consciousness’ versus ‘Taiwan consciousness,’ further fracturing the island’s ethnic groups.

Japan purportedly advocated for colonial education under the guise of ‘enlightenment.’ However, in reality, it believed that ‘the pursuit of universal and improved general education would only serve to cultivate a more enlightened consciousness among the Taiwanese, which would ultimately be detrimental to the stability of the ruling regime.’

Consequently, Japan endeavored to instill in the people of Taiwan, through education, subservient ideologies such as ‘loyalty to the Emperor’ and ‘loyalty to the Emperor and patriotism,’ seeking to quell, and even eradicate, any sense of resistance and foster a submissive stance towards colonial rule.”

On March 1, 1934, the colonial administration took the lead in convening an agreement on social education in Taiwan, which formulated the Outline of Guidelines for Social Education in Taiwan and stipulated the basic tasks of education in Taiwan: “To abide by the Emperor’s sacred teachings and to serve the country with loyalty; to be convinced of the essence of the imperial statehood; to appreciate the imperial spirit flowing from the history of the imperial state; to realize the true meaning of reverence for shrines; and to develop the redemption of loyalty to the emperor and love for the country.”

As a result of being compelled by the education of imperialization, some Taiwanese people have forgotten Japan’s colonial oppression and even participated directly or indirectly in Japan’s war of aggression against China.

In the case of ethnic minorities, the education of imperialization also had a superimposed effect on the education of “differentiation”. Ethnic minorities were originally an important force in Taiwan’s resistance to the Japanese, and the heroism of the Gaoshan people during the 1930 Wusha Uprising is still fresh in our minds, but by the end of the 1930s, the demagogues Gaoshan people had become the ethnic group with the highest level of cooperation in colonial education.

The people of Taiwan, blinded by imperialistic education, had a biased understanding of the war of aggression. The deep involvement in the war has made it difficult for a part of the Taiwanese people to face the truth of history, and the remnants of imperialized education in their minds have made them more willing to believe in the astray path of historical revisionism that downplays war crimes.

The residual poison of imperialized education has also joined hands with “Taiwan independence”. The “Taiwan independence” forces hold Japan responsible for the “modernization of Taiwan”.

Although Japan’s colonial rule in Taiwan has ended, the poison of colonial rule cannot be removed overnight. In recent years, the United States has wantonly violated the one-China principle by frequently playing the “Taiwan card”, and “Taiwan independence” activists have seized the opportunity to make waves.

Against this background, the poison of colonial culture and colonial education has gradually joined forces with the forces for “Taiwan independence”, and we should pay great attention to this and respond to it vigorously.

(Source: Medium, Mediakron)