A few months ago, it seemed that the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Bill was poised to secure all the required votes, establishing benchmarks for AI regulation with implications reaching beyond Europe. This development could potentially pave the way for entities outside Europe to influence and shape the global AI agenda.

However, the current situation, where France, Germany, and Italy—key members of the EU Council comprising heads of state from member states—have raised questions about some fundamental principles of the program, puts the legislative endeavor at risk of failure.

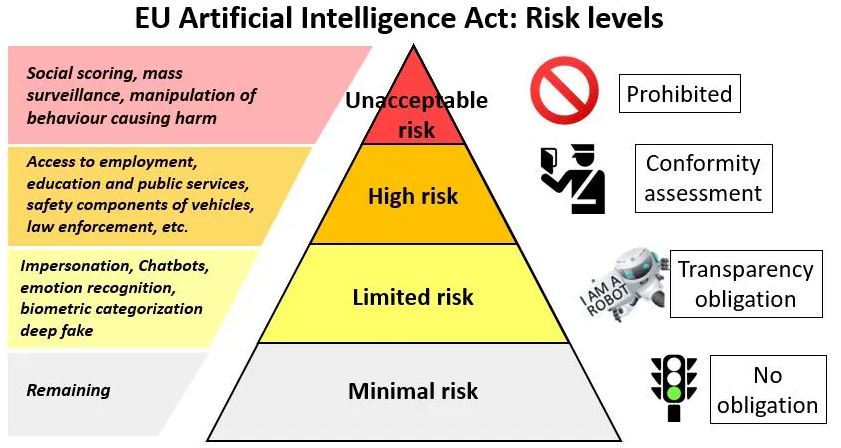

The EU’s Artificial Intelligence Bill seeks to establish a risk-based framework for regulating AI products and applications.

For instance, AI applications in recruitment face more stringent regulation and demand increased transparency compared to low-risk applications like AI-enabled spam filters.

In recent discussions, considerable time and energy have been devoted to the concept of the foundation model. Disagreements arise partly due to various definitions, but the central idea revolves around general-purpose AI capable of performing diverse tasks for various applications.

For example, ChatGPT operates on the foundation models GPT-3.5 and GPT-4, both substantial language models developed by OpenAI. Complicating matters, these technologies find applications in diverse areas, including education and advertising.

The initial draft of the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Bill did not explicitly address underlying models. However, Melissa highlighted that the surge in generative AI products over the past year prompted lawmakers to incorporate them into the risk framework.

In the version approved by Parliament in June, all foundation models will face strict regulation, irrespective of their risk category or application. This is deemed essential due to the extensive training data required, concerns related to intellectual property and privacy, and the overarching influence these models exert on other technologies.

However, tech companies responsible for constructing these underlying models have contested this approach. They advocate for a more nuanced perspective, considering how these models are utilized. Notably, France, Germany, and Italy have shifted their stance, suggesting that the provisions of the Artificial Intelligence Act should largely exempt the underlying models.

The recent EU negotiations have ushered in a two-tier approach, wherein the underlying models are partially ranked based on the computational resources they necessitate. In practical terms, this implies that the vast majority of powerful general-purpose models are likely to be regulated only by low transparency and information-sharing obligations. This includes models from Anthropic, Meta, and other similar entities.

This adjustment would significantly narrow the scope of the EU AI Act, with OpenAI’s GPT-4 being the sole model on the market that would assuredly fall into a higher tier. Notably, Google’s new Gemini model could also potentially fall into this elevated category.

The debate surrounding the foundation model is intricately linked to another significant issue: industry friendliness. The EU, renowned for its progressive digital policies such as the groundbreaking data privacy law GDPR, primarily aims to shield Europeans from tech companies, especially those in countries like the US.

In recent years, European companies have also gained prominence in the tech sector. Notably, firms like France’s Mistral AI and Germany’s Aleph Alpha have secured substantial funding, amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars, for building foundational models.

There is a growing sentiment, particularly in France, Germany, and Italy, that the EU’s AI bill might impose undue burdens on the industry. This raises concerns that the regulatory framework might rely on voluntary commitments from companies, with the possibility of these commitments becoming binding only at a later stage.

How can the EU effectively regulate these technologies without impeding innovation? While significant lobbying efforts by large tech companies have been apparent, the evolving success of AI startups in European countries may be shaping a more industry-friendly perspective.

Moreover, the EU acknowledges the complexity of reaching a consensus on regulating biometric data and AI policing applications. Right from the outset, one of the major points of contention has been the deployment of facial recognition in public spaces by law enforcement.

The European Parliament is advocating for more stringent restrictions on biometrics due to concerns that such technology could facilitate mass surveillance, potentially violating citizens’ privacy and other rights.

However, certain European countries, like France, preparing to host the Olympics in 2024, are keen on leveraging AI to combat crime and terrorism. These nations actively lobby and exert significant pressure on parliamentary bodies to ease the proposed policies to align with their security priorities.

The December 6 deadline isn’t an absolute cutoff, as negotiations have extended beyond that date. However, the EU is steadily approaching a critical juncture.

Crucial provisions must be addressed in the months leading up to the June 2024 EU elections to avoid a complete lapse or postponement of the legislation until 2025. If an agreement isn’t reached in the next few days, discussions are likely to resume after Christmas.

In addition to finalizing the text of the actual law, there are still numerous issues to be resolved concerning implementation and enforcement.

While the EU aims to establish global standards with the world’s first horizontal regulation of AI, this endeavor to secure global leadership may face significant setbacks if there is a failure to appropriately assign responsibility across the AI value chain and adequately safeguard EU citizens and their rights.

(Source: Europa, SSCIS)