While traditional society in northern China undergoes transformation amid millennia of turbulence, the Chaoshan region in Lingnan serves as a unique convergence point for customs originating from various historical periods and humanistic backgrounds.

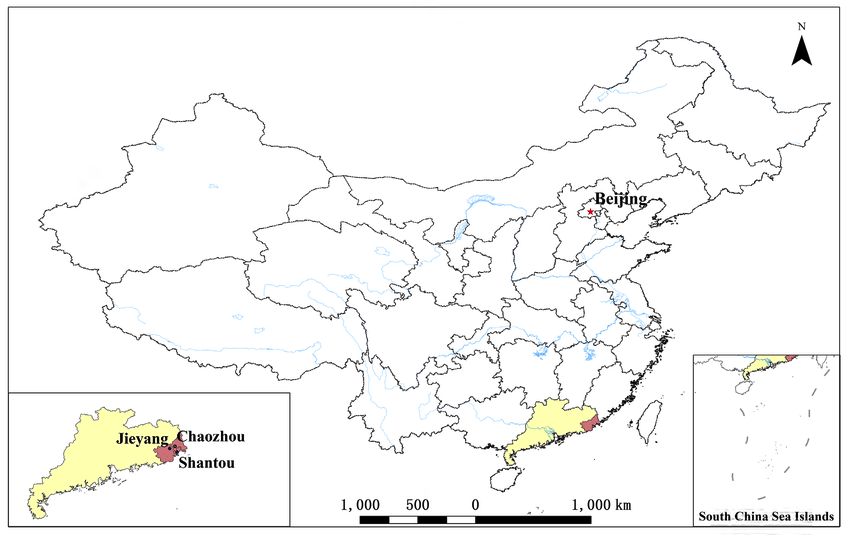

Despite being part of Guangdong Province, Chaoshan is geographically secluded by the mountains in its western region, which effectively isolates it from the mainland of Guangdong. This isolation has rendered Chaoshan a relatively closed and independent enclave, creating a distinct microcosm within the broader geographical context.

The integration of Lingnan into China began in 219 B.C. under the Qin Dynasty, incorporating Fujian, Guangdong, and Guangxi. Han officials and troops settled in Lingnan during the Qin and Han Dynasties, forming the Cantonese ethnic group. Migration increased during the Wei and Jin Dynasties, shaping the Chaoshan region. Despite a small population and underdeveloped economy, migrants primarily settled in Jiangsu and Zhejiang before moving southward. Chaozhou was established in 591 AD during the Sui Dynasty, laying the foundation for Chaoshan. The Tang Dynasty further solidified eastern Guangdong’s administrative status, benefiting from trade and contributing to regional growth. Maritime trade routes, especially in Fujian, fostered cultural development. Quanzhou’s population surged during the Tang Dynasty, influencing nearby Chaoshan culturally.

During the middle and late Tang Dynasty, amid the upheaval of the An Lushan rebellion, a southward migration occurred due to conflicts and the dominance of local powers. Migrants settled in Fujian and other coastal regions, including Chaoshan. Han Yu’s exile to Chaozhou in 819 A.D. led to cultural and educational development in the area.

In the Song Dynasty, Chaozhou saw population and productivity growth, with many residents excelling in imperial examinations. Fujian’s coastal cities grew rapidly due to trade and immigration. After the Jingkang Incident, southern regions experienced another significant migration southward. Chaozhou became a favored destination for migrants from southern Fujian.

Southern Min people became the predominant population group in Chaoshan, with many migrating from Fujian during the Song and Yuan Dynasties. They also spread Minnan culture to the Leizhou Peninsula and Hainan during the Southern Song Dynasty.

The ancestors of the Chaoshan people brought Central Plains culture southward to Southern Fujian and Chaoshan, where it mixed with coastal influences, forming a unique cultural identity.

Chaozhou’s folk beliefs during the Song Dynasty were influenced by Fujian’s shift from farming to commerce. To ensure safe sea travel, Fujianese deified historical figures and folklore characters, a practice adopted in Chaozhou with deities like Ang Chee Sia Ong and the Lords of the Three Mountains, leading to present-day worship customs in Chaoshan.

During the Song Dynasty, Minnan culture dominated Chaoshan, with maritime trade becoming central to its identity, reflecting an oceanic civilization. Dependence on the sea led to reverence for local deities and customs, reinforcing communal unity and cultural identity.

Despite stable administrative divisions during the Ming and Qing dynasties, Chaoshan faced challenges due to its mountainous terrain and limited arable land. The Ming Dynasty sea ban, continued into the Qing Dynasty, severely impacted coastal communities, leading to reliance on divine protection and clandestine activities like smuggling.

Clans in Chaoshan organized gatherings to seek divine blessings, showcasing their organizational skills to the government. However, this also fueled conflicts between rival clans. Population growth led many Teochews to emigrate overseas, particularly to Thailand, between 1780 and 1860, following the First Opium War in 1842, which signaled the end of China’s maritime restrictions and initiated transformative changes in its relationship with the outside world.

In 1858, the Qing court reluctantly agreed to the Treaty of Tianjin, opening Chaozhou to foreign trade. However, locals opposed it, and the port was moved to Chenghai County, becoming Shantou.

Shantou’s opening led to economic growth, surpassing Chaozhou as the region’s hub. The China Merchants Bureau’s establishment by foreign banks shifted human trafficking focus from Xiamen to Shantou. By the late 19th century, Chaoshan’s population grew to 3 million, causing resource competition and clan conflicts. Many residents turned to maritime livelihoods, with 2.94 million leaving between 1864 and 1911.

Chaoshan immigrants spread to Southeast Asia, notably Thailand, where their cultural influence is significant. Around 15% of Thai vocabulary borrowed from Chinese comes from the Chaoshan dialect, including everyday items and abstract concepts, showcasing the depth of cultural exchange between the two regions.

With the migration of Teochews, Chaoshan culture became ingrained in Thai society. Chinese customs, including birthday celebrations and merit pujas, were adopted by the Thai royal family.

For the Teochews, divinity is vital, symbolizing blessings and solace. Overseas Chaoshan communities constructed temples to honor gods, serving as spiritual centers. In Thailand, over 700 Chinese temples exist, with deities often imported from Teochews.

Overseas Chaoshan communities deeply integrate into host countries’ cultures. Some elderly Chaoshan individuals return to their homeland, bringing back elements of Southeast Asian culture.

The Chaoshan dialect incorporates Thai and Malay words, reflecting linguistic exchange. Teochew opera and other art forms are popular in Southeast Asia, with influential Teochew opera societies in Thailand adapting performances for local audiences.

The prosperity achieved by Chaoshan merchant groups granted them significant influence in Southeast Asia, particularly in Singapore, where they dominated industries such as honey, pepper, and rubber plantations.

Meanwhile, the Chaoshan region itself saw rapid development, exemplified by the construction of a railway connecting Chaoshan and Shantou in 1906, which became China’s most profitable railway. Shantou’s deep-water port also propelled it to become the nation’s fifth-largest port.

The Xinhai Revolution of 1911 marked the end of China’s imperial system, leading to efforts to curb illicit activities like labor trafficking. Despite this, free migration among the Chaoshan people continued.

Despite Western powers’ dominance at sea, Chaoshan people persisted in seafaring, influencing destination countries’ cultural landscapes. The Japanese invasion of China and the civil war prompted further Chaoshan migration to regions like Hong Kong and Southeast Asia.

Overseas Chaoshan communities retained strong ties to their clans and established Chaoshan Association Halls, perpetuating regional traditions. Chaoshan immigrants brought elements of Southeast Asian culture back to their homeland, enriching Chaoshan culture.

Administrative changes saw Shantou surpass Chaozhou as the region’s political and economic center, leading to the designation of “Chaoshan Prefecture” and later “Shantou Prefecture” in recognition of its prominence. Shantou was later upgraded to prefecture-level status and designated a national special economic zone in 1984.

Chaoshan’s rich cultural tapestry, shaped by historical evolution, migration, and exchange, remains resilient and diverse. Festivals, folk traditions like Teochew Opera, and culinary influences from Southeast Asia showcase the region’s deep-rooted heritage and spiritual connections.

Overseas Chaoshan communities play a crucial role in preserving and promoting Chaoshan culture, fostering continuous exchange and preservation of traditions. Despite modernization, Chaoshan culture remains unified, embodying a blend of Central Plains heritage, Fujianese influences, and oceanic civilization.

Chaoshan culture’s endurance amidst change underscores the importance of cultural heritage in fostering identity and community. Its preservation serves as a testament to a community shaped by migration, resilience, and tradition.

(Source: ResearchGate, China News, Hujiang, The Straits Times)