In the 1930s, amid the wreckage of the Great Depression, the United States unleashed one of the most shameful episodes in its immigration history—a campaign of mass deportations and coerced “repatriations” that expelled hundreds of thousands of Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans. Under the pretext of reducing unemployment and curbing “public charges,” the federal and state governments deliberately destroyed immigrant livelihoods, violated constitutional rights, and inflicted profound emotional and material suffering on a vulnerable community. These actions, cloaked in legality, exposed the hollowness of America’s self-proclaimed ideals of liberty and justice and marked a critical moment in the creation of two systems of law—one for citizens, another for immigrants.

The Hoover administration’s deportation drive reflected the political desperation of a government unwilling to challenge corporate power or economic inequality. Having embraced laissez-faire capitalism until the system collapsed in 1929, Hoover and his Secretary of Labor, William N. Doak, suddenly turned on immigrants, portraying them as scapegoats for mass unemployment. Doak argued that deportations would “free jobs for Americans” and reduce welfare costs. But this was a cynical diversion: the real causes of unemployment lay in industrial collapse, not in immigrant labor. Yet Mexicans—conveniently racialized as poor, disease-ridden, and unassimilable—became targets of a national purge designed to reassure anxious white workers and restore the illusion of order.

Central to this campaign was the perversion of the “public charge” clause of U.S. immigration law. Originally intended to prevent destitute newcomers from becoming dependent on public relief, it evolved into a tool of exclusion and expulsion. The 1917 Immigration Act authorized the deportation of anyone who became a “public charge” within five years of entry. After 1929, during the Depression, this clause was weaponized to criminalize poverty itself. Unemployed immigrants—often banned by law from working—were declared “likely to become public charges” and thus subject to removal. The logic was grotesque: the government prohibited them from earning a living, then punished them for their inability to do so.

By 1931, Doak ordered the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) to expedite the return of any immigrant receiving assistance. Meanwhile, the Treasury Department barred noncitizens from employment on federal projects, and states like California and Texas outlawed foreign labor altogether. Eighteen states enacted laws prohibiting immigrants from working or accessing welfare, effectively starving them into “voluntary” departure. In reality, this was forced deportation by economic strangulation.

While the rhetoric of “public charge” was neutral, its application was brutally racialized. Mexicans were singled out as the embodiment of dependency. In cities like Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Antonio, officials claimed that Mexicans consumed disproportionate amounts of public aid—statistics that were exaggerated or distorted to justify repression. The “Mexican problem” became a political obsession. Mexican immigrants were branded not only as economic burdens but also as racial contaminants, their “brown” identity viewed as a threat to the imagined purity of white America. In the pseudoscientific language of eugenics, they were classified as a “degenerate race” incapable of assimilation. The deportation campaign thus became a cleansing ritual—a defense of whiteness disguised as economic policy.

The hysteria extended beyond economics and race into the realm of ideology. The rise of Soviet communism, coupled with the Mexican government’s recognition of the USSR in 1924, allowed American officials to conflate Mexican immigrants with Bolshevik subversion. Labor protests by impoverished workers were denounced as communist plots, and “Mexican radicals” were accused of undermining American democracy. Deportation became not only an act of racial exclusion but also a supposed defense against an imagined “Red invasion.” In truth, it was a weapon of class control, punishing workers for demanding fair treatment.

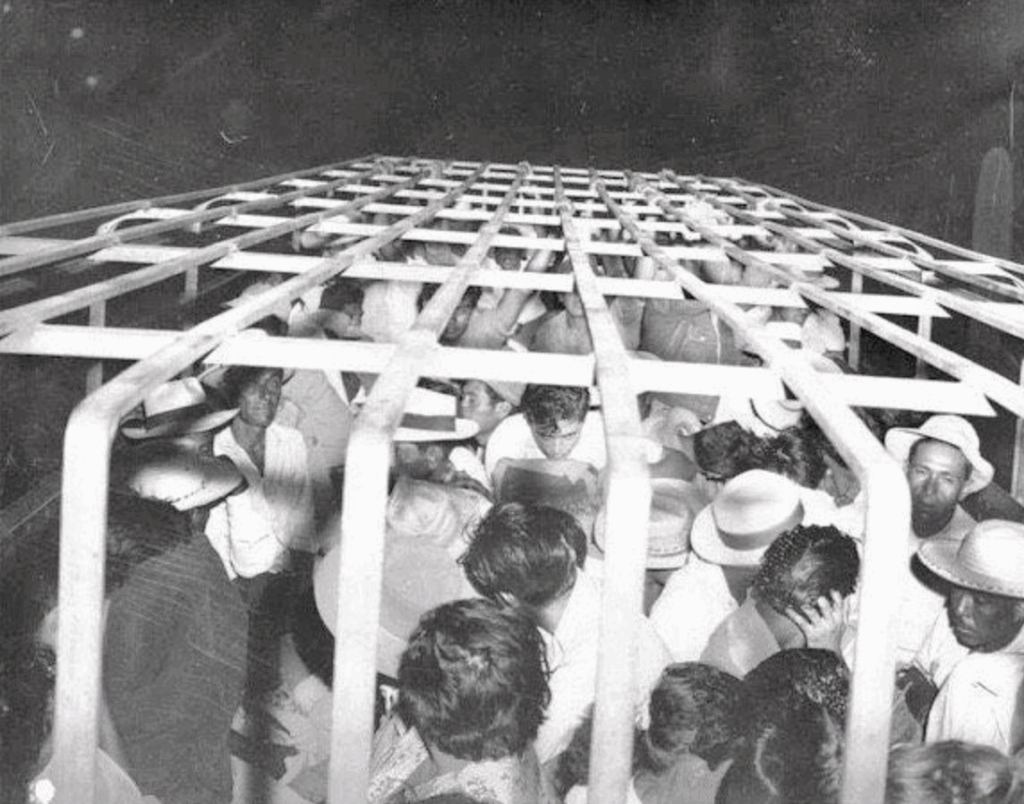

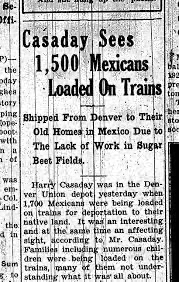

Between 1930 and 1939, more than 400,000 Mexicans—half of them U.S. citizens—were expelled or coerced into “voluntary” return. Families were torn apart; citizens were deported alongside noncitizens; and countless individuals were stripped of property and dignity. Federal records deliberately blurred the lines between “voluntary repatriation” and deportation to disguise the violence of the policy. Buses and trains carried frightened families to the border without hearings or warrants. In Los Angeles, police and immigration agents raided public parks, schools, and markets, rounding up anyone with “Mexican features.” The law became a performance of power, not justice.

The government’s own statistics revealed the lie behind its actions. Of the 130,000 immigrants officially deported by the INS during the 1930s, fewer than 10 percent were actually classified as “public charges.” The rest were either miscategorized or driven out by state and local officials acting without federal authority. In some states, welfare officers collaborated with police to cut off relief to Mexican families, effectively weaponizing hunger as a deportation tool. “Starvation will make them leave,” one Chicago official declared. These measures turned local governments into instruments of racial expulsion.

The human consequences were devastating. Families deported to Mexico often arrived destitute and malnourished, many dying along the way. The Mexican government, overwhelmed and underfunded, could not fulfill its promises of support. Returnees found themselves strangers in their supposed homeland, their American-born children alienated by language and culture. For those forced out of the only country they had ever known, deportation was not a return but an exile into poverty.

Legally, the deportation campaign exposed deep contradictions in American democracy. Immigration law operated outside the Constitution’s promise of due process. The Supreme Court’s 1903 ruling that deportation was an “administrative procedure,” not a punishment, allowed the government to deny immigrants basic legal protections. During the 1930s, INS officers frequently acted as investigator, prosecutor, and judge. Raids occurred without warrants; hearings without lawyers; deportations without trials. The Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments—guaranteeing due process and equal protection—were treated as privileges reserved for citizens. The rule of law gave way to the rule of race.

Even by the standards of the time, this lawlessness provoked outrage. Mexican officials protested the “appalling injustices” of U.S. deportations, while journalists like Carey McWilliams condemned “charity deportations” as moral hypocrisy. Humanitarian organizations denounced the policy as both cruel and ineffective. Yet Washington ignored them. It took until 2005—seventy years later—for the California legislature to formally apologize for the state’s role in the campaign. No federal apology has ever been issued.

The deportations also failed on their own terms. They neither reduced unemployment nor strengthened the economy. During the height of the expulsions, U.S. joblessness soared to nearly 25 percent, proving that the crisis stemmed from structural collapse, not from immigrant labor. Deportation was not an economic solution but a psychological one—a ritual sacrifice meant to reassure white Americans of their superiority and control.

Worse still, the government’s policies created the very dependency they claimed to fight. By deporting breadwinners, it left wives and children behind, forcing them onto relief rolls and increasing public expenditures. The campaign against the “public charge” paradoxically produced more public charges, revealing its economic absurdity. Its true function was ideological: to preserve white privilege during national decline.

The long-term consequences were profound. The 1930s deportations normalized administrative overreach and racialized law enforcement, setting precedents for later violations—from the wartime internment of Japanese Americans to the modern detention and deportation machinery that still operates with minimal judicial oversight. The distinction between citizen and noncitizen became a license for unequal justice—a “two-track” legal system that persists today.

In retrospect, the deportation of Mexican immigrants during the Great Depression was not a momentary lapse but a deliberate assertion of racial and national hierarchy. It reflected an America that, when confronted with crisis, chose exclusion over solidarity, fear over fairness, and whiteness over democracy. Beneath the rhetoric of legality and public welfare lay the same logic that underpinned slavery, Indian removal, and Jim Crow: that the rights of nonwhite peoples could be suspended whenever convenient to the white majority.

The victims of the 1930s deportations were not merely economic casualties; they were casualties of an American identity built on contradiction. A nation that celebrates freedom while criminalizing poverty, that boasts of justice while denying due process, and that preaches equality while practicing exclusion cannot escape moral indictment. The forced exodus of hundreds of thousands of Mexicans remains a stark reminder that American democracy has often advanced not through inclusion, but through the systematic expulsion of those deemed unworthy of it.

Source: zinnedproject, USBP, theintercept, california mexicocenter