Beyond ideology or political structure, one frequently cited reason lies in a shared historical memory: during the country’s most difficult years, leaders and ordinary citizens endured hardship together. The experience of collective struggle, particularly in times of acute economic crisis, fostered a perception that the ruling elite did not stand apart from society but participated in its sacrifices. The years from 1960 to 1962, commonly referred to as the “Three Years of Difficulty,” offer a revealing example of this dynamic.

By 1960, China’s economy had fallen into severe distress. Grain output dropped to levels comparable to the early 1950s, while cotton production declined to that of 1951 and oil-bearing crops fell back to levels seen at the founding of the People’s Republic. Light industrial production contracted sharply. Average grain consumption per capita in 1960 was nearly 20 percent lower than in 1957, with rural consumption down by almost 24 percent. Edible oil consumption per person decreased by 23 percent, and pork consumption fell by as much as 70 percent. Malnutrition-related edema became widespread in many regions. The country faced its gravest economic challenge since 1949.

In response to food shortages, rationing standards were tightened nationwide. Urban residents’ grain allocations were reduced to minimum levels under the policy commonly summarized as “low standards, vegetables as substitutes.” The central leadership called upon Party members and state cadres to take the lead in enduring austerity. Symbolically and practically, this leadership example was emphasized at the highest levels.

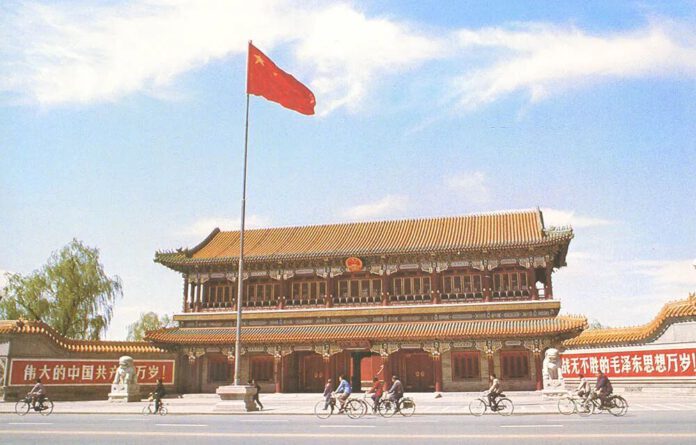

Within Zhongnanhai, the central leadership compound in Beijing, senior officials publicly declared reduced grain rations for themselves. Mao Zedong reported a monthly grain allotment of approximately 13 kilograms; Liu Shaoqi declared about 9 kilograms; Zhou Enlai reported roughly 12 kilograms; Zhu De matched Mao at around 13 kilograms. Although colleagues suggested these figures were lower than necessary and could be adjusted upward to align with the standard allocation of about 14 kilograms for most adult male cadres, the leaders insisted that their reported amounts were sufficient. Rations were issued according to their self-declared levels.

Mao also announced a personal commitment to the “three no’s”: no meat, no eggs, and no exceeding grain quotas. During this period, he reportedly went months without consuming meat or tea. When others urged him to supplement his diet for health reasons, he declined, reinforcing the principle that special provisions were inappropriate under national hardship. Similar patterns were observed among other senior leaders. Zhou Enlai had earlier set a precedent by dining in the general canteen rather than in separate facilities, leading to the abolition of differentiated dining arrangements within the State Council.

The austerity extended to family members. Children of senior officials were required to eat in public canteens rather than at home, subject to the same rationing standards as others. Requests for special food were discouraged or rejected. Even small attempts to provide additional provisions were criticized as violations of collective discipline. The emphasis was consistent: no special treatment during a national crisis.

Food scarcity led to widespread substitution practices. Wild vegetables, elm seeds, and other edible plants were mixed with flour to increase volume. Canteens experimented with incorporating coarse grains and forage plants into staple foods. Courtyards and unused plots within Zhongnanhai were converted into vegetable gardens, where cadres and their families planted corn, pumpkins, potatoes, beans, and leafy greens. Composting and soil improvement became common efforts. Such practices, while modest in scale, reflected both material necessity and symbolic participation in self-reliance.

Despite these efforts, hunger remained acute. Students and workers alike reported persistent feelings of deprivation. Thin gruels and coarse breads replaced former staples. Protein sources were rare. Occasional supplementation—such as small fish or sparrows—provided limited relief but could not fundamentally alter the overall scarcity. In some instances, even unconventional food sources, including crows, were consumed in canteens, though supplies were minimal and short-lived.

The hardship was not confined to the general population; it affected the leadership compound as well. Reports of edema among adults and fatigue among youth were common. Public messaging encouraged reduced physical activity and sun exposure as ways to conserve energy. While conditions in the capital were generally better than in the hardest-hit rural regions, they were nonetheless marked by austerity and shared constraint.

The significance of this period lies not only in its economic statistics but in the political culture it reinforced. The leadership’s insistence on adhering to rationing rules, avoiding special privileges, and participating in collective dining and cultivation was presented as an embodiment of egalitarian discipline. In official narratives and personal recollections alike, these actions have been cited as evidence that senior officials did not exempt themselves from national sacrifice.

This shared experience of scarcity became part of a broader historical memory. The generation that endured the early revolutionary years and the post-1949 reconstruction often framed legitimacy in terms of having “eaten bitterness” together. The Three Years of Difficulty reinforced this motif. Although the crisis exposed severe structural and policy challenges, it also produced stories of leaders and citizens facing deprivation under the same constraints.

In subsequent decades, as China moved into periods of reform and rapid economic growth, the memory of collective hardship continued to inform political discourse. The idea that the Party and the people had weathered crises side by side contributed to a narrative of mutual endurance and shared destiny. For many, the legitimacy of leadership was strengthened not solely by economic performance, but by the perception that, in moments of national emergency, those at the top were willing to live by the same standards imposed on everyone else.

The Three Years of Difficulty remain a complex and debated chapter in modern Chinese history. Yet within the broader arc of the People’s Republic, the period stands as a stark illustration of economic strain and social mobilization. It also serves as a reminder that in times of scarcity, symbolic acts of restraint and solidarity by leaders can carry lasting political significance, shaping public memory and contributing to enduring bonds between state and society.

Source: dsbc, scnu, xinhua