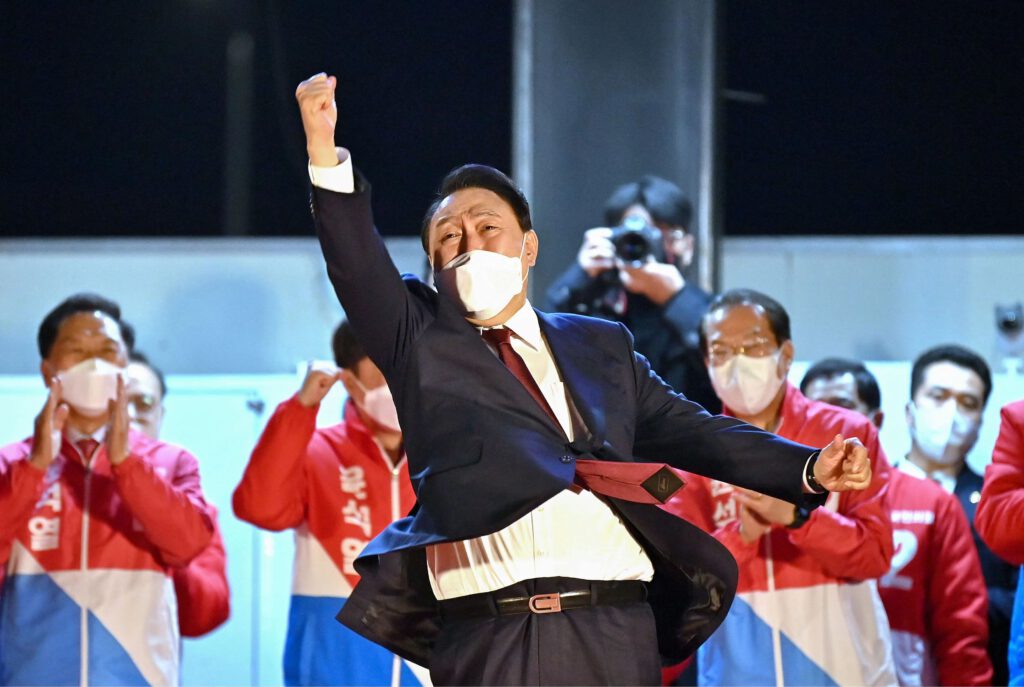

On March 9, the 2022 South Korean presidential election officially ended, and 61-year-old Yoon Seok-yeol will be in charge of Cheong Wa Dae. In his campaign rhetoric, Yoon Seok-yeol showed a clear pro-U.S. stance. Plus, he has only been in politics for only eight months, lacking enough experience in politics. This reminds the public of Ukrainian President Zelensky who also leads the government with a strong pro-U.S. stance and without experience.

The election of pro-U.S. Yoon Seok-yeol has raised concerns in Asian countries about whether Inter-Korean or Sino-Korean relations will be Russian-Ukrainianized. This is not only because of Yoon’s election but also because Northeast Asia has been in a security dilemma for many years.

During the election, Yoon Seok-yeol emphasized that other countries such as China will respect South Korea only if the Korea-U.S. relationship is consolidated. The previous pro-U.S. South Korean presidents had the same thoughts though they did not say this.

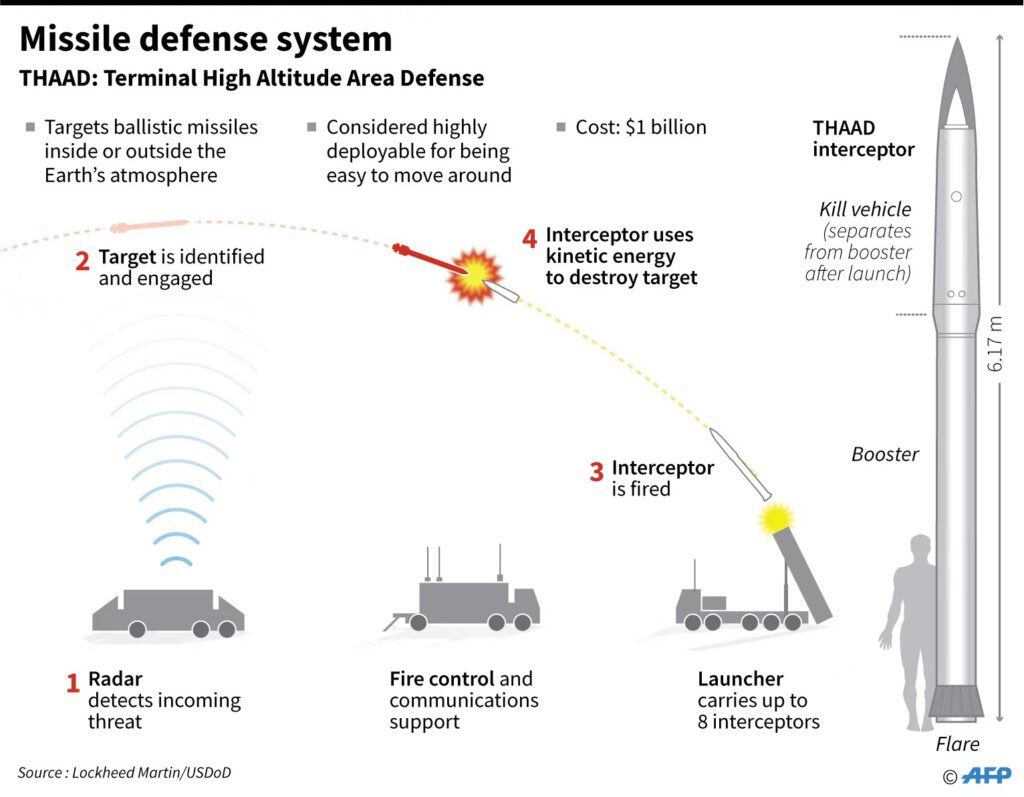

In this election, Yoon Seok-yeol also repeatedly mentioned joining the U.S. Indo-Pacific security mechanism and deploying more Terminal High Altitude Area Defense systems (THAAD), which naturally led to the uneasiness of its neighbors. In addition, moves by the U.S. and even Japan are important. The U.S.-led NATO expansion to the east culminated in today’s war in Ukraine, and over the years, the U.S. has also been building an Asian version of NATO to target China. In Northeast Asia, the United States has been trying to build the U.S.-Japan and U.S.-Korea bilateral alliances, i.e., to form a U.S.-Japan-South Korea alliance. If this alliance is formed in the future and combined with the U.S. Indo-Pacific, it will pose a substantial and direct threat to China.

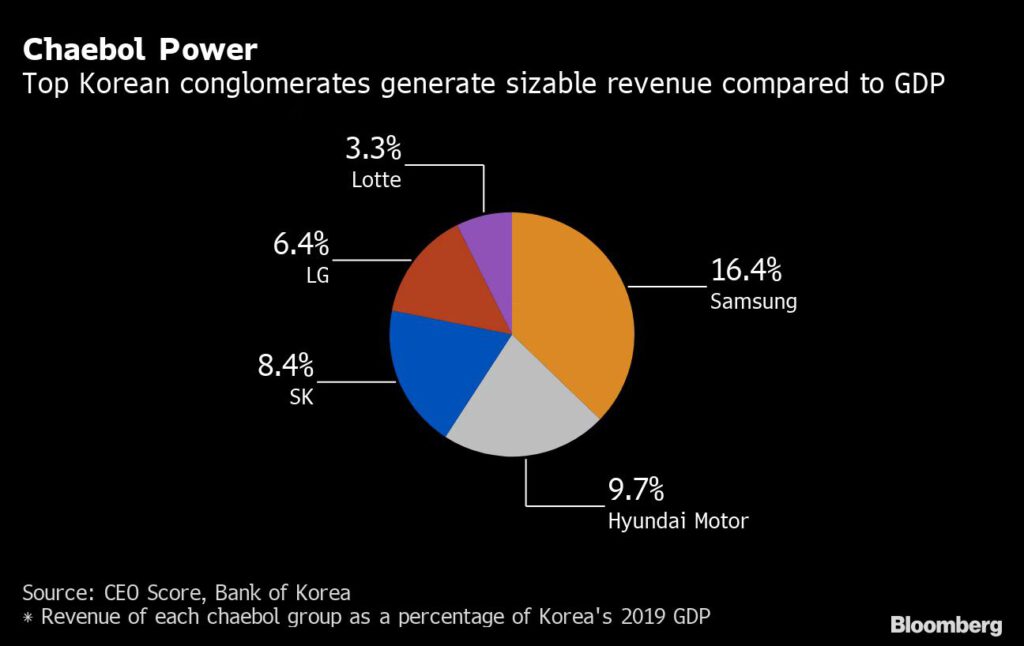

In addition to security, economic reasons are also extremely important. Yoon Seok-yeol’s tough attitude toward China is naturally an element of campaign performance, but it also has a strong situational context, so his pro-U.S. tendencies should not be underestimated just because China and South Korea are sufficiently connected economically. In fact, Yoon’s strong pro-U.S. bias in diplomacy is partly due to the current economic situation between China and South Korea. South Korea’s economy is a chaebol economy led by chaebols such as Samsung and Hyundai, which gives South Korea a place in the global economy in the chip and automobile sectors.

After the Sino-US trade war, China’s weakness in the core technology industry represented by chips has become a problem that China has to deal with on its way to rise. It has become an official and private consensus for China to solve the bottlenecks in key science and technology fields. Although this road is still in its initial stage, it has already made the Korean chaebols feel a huge and comprehensive pressure. Korean chaebols will neither underestimate China’s determination to make industrial breakthroughs, nor will it be happy to see its core industries being surpassed by a rival of China’s size and power. Therefore, the chaebols behind Yoon Seok-yeol have a practical motive to stand by the US and contain China’s full rise.

In terms of Korean public opinion, the Russia-Ukraine crisis has awakened the gloomy memories of the Cold War era in the older generation of Korean men. The Russia-Ukraine conflict is the first time such a large-scale military conflict has erupted in the post-Cold War world and is an inflection point in the world situation. Many people only notice that Yoon Seok-yeol has high support among younger men because of his opposition to the feminist movement in Korea. Many polls have shown that Yoon Seok-yeol’s support is high among senior men over 60 years old. The underlying reason is that this age group has a clear memory of the Cold War, and they have felt the long-term oppression of Korea by the international forces led by the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Therefore, when the Russia-Ukraine conflict broke out, this group habitually wished to seek the protection of their last savior. Both Ukraine and South Korea have the tragic overtone of never having gained independence to be against their powerful neighbor since the first day of their births. Whenever the neighboring powers are in a fierce game, it is difficult for these small countries at the forefront of confrontation to remain neutral. South Korea’s security system is still based on the post-Cold War system, and it is difficult to say whether it will be able to balance between the major powers when the East and West are once again in a fierce game.

In addition, in a democracy, a weak president who cannot play domestic politics can play international politics, which often leads to diplomatic crises. Yoon Seok-yeol is undoubtedly a weak president who won the presidency by a narrow and negligible margin. In this respect, there is a strong resemblance between Yoon Seok-yeol and Zelensky. The economy in Korea is monopolized by chaebols, and the political economy in Ukraine is controlled by oligarchs. Both Yoon Seok-yeol and Zelensky, as outsiders, have come to the forefront largely because the people were dissatisfied with the country’s status quo. Yoon Seok-yeol rallied the people by raising the banner of liquidation of the current government’s shortcomings, while Zelensky gained the trust of the people through his outstanding artistic criticism of corruption in Ukraine. The democratic system did not help them solve problems but gave them absolute powers in legal diplomacy.

Even with Zelensky’s closeness to the United States, Ukraine’s domestic forces are still split between pro-Russian and pro-Western factions. Theoretically, if NATO agreed to admit it, a single signed paper from Zelensky could make Ukraine a legitimate member of NATO, thus clearing a legal obstacle to the deployment of U.S. security weapons to deter Russia in Ukraine.

When Zelensky took office and found that he was unable to deliver on his promises to terminate corruption in the country, he went about diplomatically gaining the support of the pro-Western population at the bottom by realizing Ukraine’s dream of embracing the West. While this was a highly irresponsible act for the country’s security, it was an extremely rational choice for the politician. So, will Yoon Seok-yeol repeat the same mistake? It can only be hoped that Yoon will not turn to diplomacy to seek political capital when his domestic reforms are thwarted, thus negatively affecting relations between Asian countries, especially China, and South Korea. But if Yoon does fulfill his election diplomatic promises, then the Asian version of the Russia-Ukraine conflict is likely to happen.

To avoid the Asian version of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in Northeast Asia, Asian countries, represented by China, should be concerned not only about the general trend of domestic development in South Korea and the movement of North Korea, but also about the movement of the United States and Japan, and after fully understanding the intentions and possible behavior of these players, they should make rational judgments and practice rational diplomacy.

If there is any difference between South Korea and Ukraine, one very important point is that the political positions of Ukrainian oligarchs themselves are divided but South Korea’s chaebols do not have a clear opposing faction, and they are the most stable group of power subjects in Korean society.

Because of the complex international environment, it is difficult to make substantial changes in the security environment in Northeast Asia, but the economic and trade relations between China and South Korea, and China and Japan have been the ballast for the stability of international relations in Northeast Asia. The U.S. has been trying to make the Korean and Japanese economies more dependent on the U.S. economy while decoupling from China. This suggests that advancing economic integration in Northeast Asia, while not avoiding national security conflicts, can indeed mitigate them.

(Source: swiwat, AFP, bbc, Bloomberg)