South Korea’s latest National Security Strategy (NSS) under President Yoon Seok Yeol represents a significant shift from the previous administration, with an emphasis on security, diplomacy, and economic resilience. Released on June 7, 2023, under the title Global Pivotal State for Freedom, Peace and Prosperity, his strategy positions South Korea as a central player in regional and global affairs.

It departs from the approach of Moon Jae-in’s government by prioritizing the North Korean threat, enhancing ties with the U.S. and Japan, and promoting values-based diplomacy, especially in the context of South Korea’s relationship with China.

Strategic Objectives and Security Challenges

The NSS is built around three main objectives: safeguarding national security, promoting peace on the Korean Peninsula, and contributing to prosperity in East Asia and beyond. To achieve these, South Korea will tackle four primary security challenges: North Korea’s nuclear threat, U.S.-China rivalry, economic security, and emerging non-traditional security risks. These objectives are meant to guide the nation’s defense, diplomatic, and economic policies over the next five years.

A central aspect of Yoon’s NSS is the explicit classification of North Korea as the primary security threat, marking a distinct break from the conciliatory stance of the Moon administration. North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs are highlighted as existential threats, with the NSS mentioning North Korea 157 times, contrasting with fewer references to the broader geopolitical competition between the U.S. and China. Yoon’s “3D” strategy—Deterrence, Dissuasion, and Dialogue—focuses on bolstering military capabilities and strengthening trilateral security cooperation with the U.S. and Japan. Sanctions and economic isolation are combined with denuclearization incentives, signifying a shift from Moon’s peace-oriented approach to a more security-driven policy.

Economic Security as National Defense

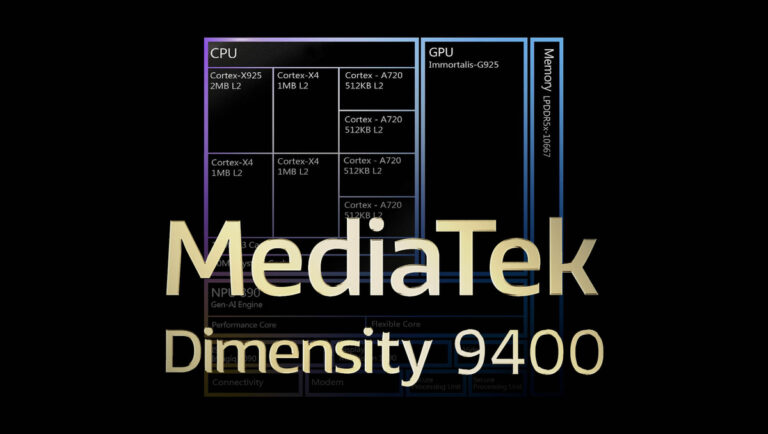

Economic security is a critical element of Yoon’s strategy, with an emphasis on addressing vulnerabilities in global supply chains, key technologies, and the transition to low-carbon economies. The NSS outlines three key approaches: first, enhancing economic partnerships with allies such as the U.S., Japan, and the EU through frameworks like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and APEC; second, the creation of new institutions like the Centre for Economic Security Diplomacy to safeguard economic interests and pass legislation protecting critical technologies; and third, the diversification of trade and supply chains to reduce reliance on specific countries, particularly in critical sectors like semiconductors and batteries.

Values-Based Diplomacy and Shifts in Regional Relationships

A distinct feature of Yoon’s NSS is its commitment to values-based diplomacy, emphasizing democratic principles, human rights, and the rule of law. This represents a departure from Moon’s pragmatic approach, especially in relations with China and Japan. Yoon’s administration prioritizes aligning South Korea’s foreign policy with nations that share similar values, positioning the country as a responsible middle power on the global stage. This shift is reinforced by South Korea’s increasing role in global challenges like climate change and public health, with a stronger focus on “contribution diplomacy” to bolster its international standing.

The NSS also redefines South Korea’s diplomatic approach toward Japan and China. Under Yoon, South Korea seeks to downplay historical tensions with Japan in favor of strategic cooperation on regional security, renewing trilateral ties with the U.S. and Japan. On the other hand, the relationship with China remains delicate. The NSS advocates for a “mature” partnership that balances security concerns, such as the deployment of the THAAD missile defense system, with economic cooperation. South Korea’s delicate diplomacy aims to maintain strong economic ties with China while aligning more closely with the U.S. on security matters.

Expanding the U.S.-ROK Alliance and Technological Collaboration

Yoon’s administration continues to view the U.S.-ROK alliance as the foundation of South Korea’s foreign policy. The NSS outlines deeper cooperation with the U.S. beyond traditional military ties, focusing on areas such as technology, economic security, and climate change. This broader alliance reflects the complexity of modern security challenges and reinforces South Korea’s strategy to navigate the growing geopolitical competition in East Asia.

In addition to shared democratic values, the South Korea-U.S. partnership increasingly revolves around technological collaboration. Initiatives like the Next Generation Critical and Emerging Technologies Dialogue are fostering cooperation in artificial intelligence, semiconductors, and quantum technology. South Korea’s participation in alliances like the Chip Quad Alliance and the Clean Network demonstrates its commitment to maintaining technological competitiveness.

This expanded alliance is not limited to bilateral relations. South Korea is part of a strategic shift toward a more interconnected system of alliances in the Asia-Pacific region, allowing for greater collaboration with European partners as well. This shift reflects South Korea’s broader security strategy, which addresses both traditional and non-traditional threats, while reinforcing its global influence.

Modernizing Defense and Strengthening Military Capabilities

South Korea’s defense strategy under Yoon places a strong focus on autonomous national defense capabilities, particularly in deterring North Korea. Several defense initiatives have been launched. These plans aim to modernize the military and enhance deterrence, focusing on deploying advanced weaponry.

A medium-term plan announced in December 2023, allocates 348.7 trillion won to defense over five years, marking a 5% annual increase. Key priorities include the development of a Korea-specific three-axis system and procurement of advanced weaponry. South Korea is also investing heavily in domestic R&D, targeting emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, cyber warfare, and drones. Additionally, domestically produced weapons like the KF-21 fighter jet are part of efforts to modernize and boost the country’s defense industry.

Constraints and Challenges

Despite its ambitions, the implementation of Yoon’s NSS faces significant hurdles. Relations with North Korea remain tense, as the regime has rebuffed peace overtures and continues missile tests, including the November 2023 launch of a military reconnaissance satellite. Diplomatic efforts with Japan are also complicated by domestic opposition to perceived concessions on historical grievances. Yoon’s pragmatic approach to Japan has triggered public protests, which, coupled with political polarization, complicate the execution of his foreign policy.

Yoon’s alignment with U.S. strategies in the region has also led to a deterioration in relations with China. Although South Korea continues to work with China on global issues like climate change, deepening military ties with the U.S. and participation in initiatives like the IPEF have created friction. This strained relationship, compounded by falling South Korean exports to China, presents economic challenges.

The Yoon administration’s NSS outlines a bold vision for South Korea’s role as a global pivotal state, anchored in strong defense, proactive diplomacy, and values-based alliances. While the strategy aims to expand South Korea’s influence, it faces considerable challenges in the form of regional tensions, domestic opposition, and shifting geopolitical dynamics. As Yoon navigates these complex challenges, the success of his ambitious foreign policy will depend on his ability to reconcile national security interests with diplomatic flexibility.

Source: overseas mofa go kr